Hâst dû dich selben liep, sô hâst dû alle menschen liep als dich selben. Die wile dû einen einigen menschen minner liep hâst dan dich selben, dû gewünne dich selben nie liep in der wârheit, dû enhabest denne alle menschen liep als dich selben, in einem menschen alle menschen, und der mensch ist got und mensche.

If you love yourself, then you love all others as yourself. As long as you love a single human being less than yourself, you cannot truly love yourself—if you do not love all others as yourself, in one human being all human beings: and this human being is God and man.

—Meister Eckehart, Sermon No. 13, “Qui audit me” (1325) in Meister Eckharts deutsche und lateinische Werke, vol. 1, p. 195 (J. Quint ed. 1936)(S.H. transl.)

On September 8, 1325, Eckehart of Hochheim, a nobleman and a Dominican priest, delivered a sermon in the Benedictine cloister of the Holy Maccabees in Cologne taking as his theme this passage from Ecclesiasticus: “He that hearkeneth to me, shall not be confounded: and they that work by me, shall not sin.” (24:30). Meister Eckehart was already a figure of some repute, having been called twice to teach at the University of Paris (where he obtained the title of Magister, by which he was known) and having three times been offered the position of provincial of his order. But this sermon, which survived in the transcription of some of the nuns who heard it, has emerged as one of the most important philosophical works of the fourteenth century. It is a theological discourse on one level, filled with mystic insights, but it is also a statement of philosophic detachment, what Eckehart calls gelâzenheit (a word which he coins) that seeks to redefine love in sacred and profane terms. But the sermon revolves about “hearing” (the archaic word “hearkeneth” of the King James version is simply “audit” in the Vulgate, or “hear”) or rather, understanding, the eternal Word. Three things, he says, prevent humans from reaching the necessary understanding: corporeality, multiplicity, and temporality. To commune with the Word, as he puts it, to “live in unity in the desert,” humans must overcome these obstacles. That struggle is the essence of human development, and in his view it rests on the development of a different attitude towards the self, fellow humans and God in which the self is overcome. This process is gelâzenheit, which might be translated as “letting go,” but certainly focuses on the sublimation of the conscious self and a willingness to forego material possessions. The images that Eckehart takes point carefully to the asceticism of the early church fathers as models for this process.

He then develops this idea in the context of a new doctrine of love in which love of self is carefully juxtaposed against the love of fellow humans and of God. He cites a passage from Paul of Tarsus in Romans 9:3 in which he wishes to be “cut off from Christ for the sake of my brothers.” Self-sacrifice is thus defined as the essence of love and the overcoming of the self (in his words, hie ist der mensche ein wâr mensche–thus is a human truly human). But this “true” human is essentially also what Eckehart calls a “just man.” For him, the demand for justice must be everything, what he lives and breathes to achieve, more important than the outer formality of religion. And it is radical in its social implications, as Eckehart the noble says “I call you not servants, but friends.” But it starts with the abandonment of temporal connections (omnia relinquere) in the quest for a mystical union with the spiritual. Daz hoehste und daz naehste, daz der mensche gelâzen mac, daz ist, daz er got durch got laze, says Eckehart—“the highest and most extreme thing that the human can give up, that is that he give up God for the sake of God.” These words may confound, and they certainly challenge the temporal and sacred authority of his time, but there is a clear internal logic to them, which challenges its audience to reject the paths they tread in favor of a new and mystical view of the world and humankind.

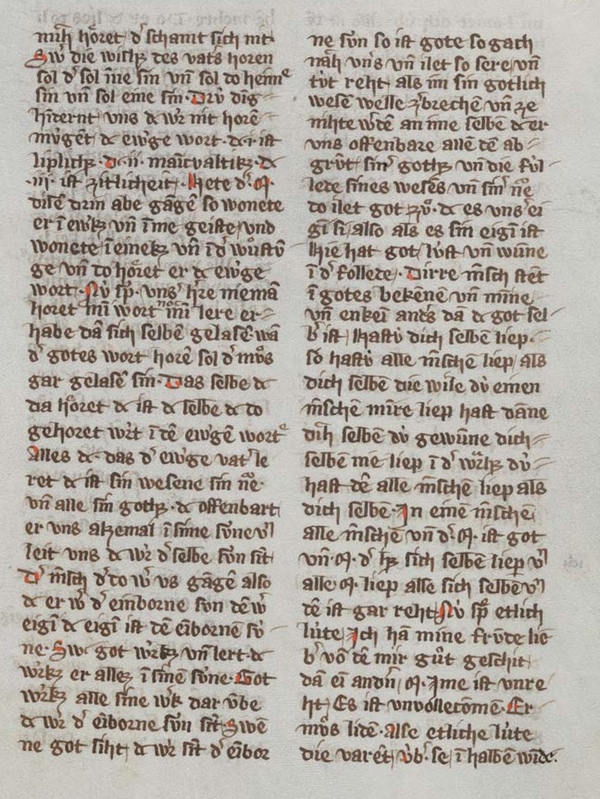

Below examine a manuscript of Meister Eckehart’s sermon “Qui audit me” dating to about 1370, found in the Stiftsbibliothek in Einsiedeln. The quoted passage is found in the right column at the middle of the page.

Listen to Michael Praetorius’s setting of Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen (1609) sung by the Toelzer Knabenchor: