Secretary of Defense Gates’s detentions-policy advisors see Guantánamo as old policy. The all-new, streamlined detentions policy goes by the name of Bagram. Looking over the new policies, there’s no doubt that they have gone some distance to satisfy their critics. But there is a serious question about the legality of the new detentions policy, and even whether it really meshes with counterinsurgency policy. Will it help win hearts and minds? Will it reinforce the legitimacy of the government in Kabul?

In Guernica and The Nation, Anand Gopal takes a close look at the United States detention policies in Afghanistan—not from the perspective of the Pentagon but rather from that of Afghan villagers and city dwellers. It’s not pretty:

Of the 24 former detainees interviewed for this story, 17 claim to have been abused at or en route to these sites. Doctors, government officials, and the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission, a body tasked with investigating abuse claims, corroborate 12 of these claims. One of these former detainees is Noor Agha Sher Khan, who used to be a police officer in Gardez, a mud-caked town in the eastern part of the country. According to Sher Khan, U.S. forces detained him in a night raid in 2003 and brought him to a Field Detention Site at a nearby U.S. base. “They interrogated me the whole night,” he recalls, “but I had nothing to tell them.” Sher Khan worked for a police commander whom U.S. forces had detained on suspicion of having ties to the insurgency. He had occasionally acted as a driver for this commander, which made him suspicious in American eyes.

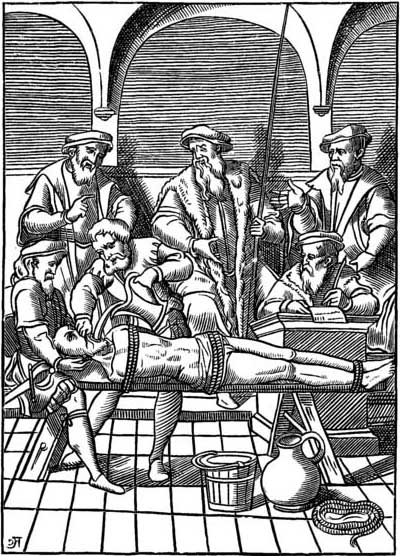

The interrogators blindfolded him, taped his mouth shut, and chained him to the ceiling, he alleges. Occasionally they unleashed a dog, which repeatedly bit him. At one point, they removed the blindfold and forced him to kneel on a long wooden bar. “They tied my hands to a pulley [above] and pushed me back and forth as the bar rolled across my shins. I screamed and screamed.” They then pushed him to the ground and forced him to swallow 12 bottles worth of water. “Two people held my mouth open and they poured water down my throat until my stomach was full and I became unconscious. It was as if someone had inflated me.” he says. After he was roused from his torpor, he vomited the water uncontrollably. This continued for a number of days; sometimes he was hung upside down from the ceiling, and other times blindfolded for extended periods. Eventually, he was sent on to Bagram where the torture ceased. Four months later, he was quietly released, with a letter of apology from U.S. authorities for wrongfully imprisoning him.

The practice that Sher Khan describes here, first used in classical antiquity and later by American soldiers battling the Filipino insurgency around the turn of the last century, is called the “water cure.” One of the JAG School textbook cases of prosecution for torture involves this procedure. The case became notorious in the United States in 1902-04, and Theodore Roosevelt personally insisted on being briefed about it, and on rigorous enforcement of the prohibition of torture. If Gopal’s account holds, then the rules that bound the military under Washington, Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Reagan really are dead, notwithstanding President Obama’s protestations that he has put an end to torture. Nearly all of the techniques that Gopal describes appear to violate the current Defense Department guidelines (with some lingering questions concerning Appendix M), but the guidelines themselves seem to have been rewritten in a way that allows the Secretary of Defense to dispense with them at will. Historically, transparency, Red Cross monitoring, and a duty to report violations have been an essential part of the system that assures fidelity to legal commitments. That has clearly changed. As Gopal notes, the United States has maintained rigorous secrecy surrounding its detention operations in Afghanistan, and Congress has created exemptions from the Freedom of Information Act for information concerning the treatment of prisoners. Gopal aims to give us a peek behind that curtain.

At least a part of this secret prison system is operated by the Joint Special Operations Command, JSOC:

The U.S. Special Forces also run a second, secret prison somewhere on Bagram Air Base that the Red Cross still does not have access to. Used primarily for interrogations, it is so feared by prisoners that they have dubbed it the “Black Jail.” One day two years ago, U.S. forces came to get Noor Muhammad, outside of the town of Kajaki in the southern province of Helmand. Muhammad, a physician, was running a clinic that served all comers—including the Taliban. The soldiers raided his clinic and his home, killing five people (including two patients) and detaining both his father and him. The next day, villagers found the handcuffed corpse of Muhammad’s father, apparently dead from a gunshot. The soldiers took Muhammad to the Black Jail. “It was a tiny, narrow corridor, with lots of cells on both sides and a big steel gate and bright lights. We didn’t know when it was night and when it was day.” He was held in a concrete, windowless room, in complete solitary confinement. Soldiers regularly dragged him by his neck, and refused him food and water. They accused him of providing medical care to the insurgents, to which he replied, “I am a doctor. It’s my duty to provide care to every human being who comes to my clinic, whether they are Taliban or from the government.”

If a medical professional takes up arms and fights with an insurgent unit, he makes himself into a legitimate target. But what the doctor told Gopal is correct as a general proposition of ethics and law. Moreover, the work a medical professional performs in this regard is protected by the Geneva Conventions and other international law. Under the Bush Administration, the United States adopted a practice of targeting as the “enemy” medical professionals who provided care to individuals it labeled as terrorists. Bush Justice Department officials deemed this “material support.” Law of war experts called these policies something else, namely a grave breach of international humanitarian law. Gopal’s narrative suggests that the Rumsfeld doctrine and its systematic denigration of the laws of war is still in place under Obama.

How does all of this stack up against the conduct of the Taliban? Gopal suggests an answer to that question, too:

It has become a predictable pattern: Taliban forces ambush American convoys as they pass through the village, and then retreat into the thick fruit orchards that cover the area. The Americans then return at night to pick up suspects. In the last two years, 16 people have been taken and 10 killed in night raids in this single village of about 300, according to villagers. In the same period, they say, the insurgents killed one local and did not take anyone hostage.

One of the key benchmarks likely to influence the conflict in Afghanistan is this: who abuses and mistreats the civilian population the least? Brutality abounds, and it is by no means clear that the Americans have the upper hand when it comes to being nice to the natives.