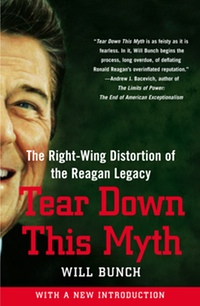

Will Bunch is an award-winning senior writer for the Philadelphia Daily News and a senior fellow with Media Matters for America. His latest book, Tear Down This Myth: The Right-Wing Distortion of the Reagan Legacy, just out in paperback, examines the process by which Ronald Reagan was subjected to a makeover after his death. I put six questions to Will Bunch about the book.

1. Your book describes itself as a deconstruction of the myth of Ronald Reagan. But how successful has the effort at myth-making been? How does Reagan now stack up among the presidents among historians and the public in general?

It’s interesting–Reagan’s reputation has risen with both the public and historians the further we get in memory from his actual presidency–which I think is a huge tribute to both the myth-making machinery created by the likes of Grover Norquist and the mainstream media’s willingness to embrace the myth. For example, in March 1990, some 13 months after Reagan left the Oval Office, Reagan’s popularity (59 percent) had dipped below that of Jimmy Carter (62 percent). Two major surveys of historians in the mid-1990s rated Reagan’s presidency as below average, not one of the all-time greats.

Ironically, it was those historian rankings that inspired Norquist, the Heritage Foundation, and others to begin what became the Ronald Reagan Legacy Project–the group that aims to name schools, roads, etc., for the Gipper in every U.S. county–and related activities. A key part of that myth-building was the notion that Reagan was largely responsible for “winning the Cold War”–a premise that was rejected, according to a USA Today poll in 1989, when it was actually happening, by Americans crediting Mikhail Gorbachev for the reforms instead. You see the fruits of that effort today; professors–arguably eager to show they’re not tools of liberal bias–now rate Reagan as high as the Top Ten of U.S. presidents, and public opinion of the 40th president is fairly high as well.

2. Lincoln’s birthday passed last week. It was remarkable that few Republicans paused to notice or to note the importance of the nation’s first Republican president. Is there a relationship between the fading away of Lincoln as a Republican icon and the rise of Ronald Reagan?

As the American electorate grew not only younger but more non-white and more nonreligious than ever before, the early years of Obama’s presidency would have been an ideal time for the Republican Party to reinvent itself, to promote a center-right path to the American dream that would be inclusive for Latinos, African-Americans or other growing blocs of voters, one rooted in economic freedom while moving away from xenophobia and religious intolerance. Instead the GOP retreated within itself, retreated within the myth of Ronald Reagan. When six candidates competed in a public forum to become the new chairman of the Republican National Committee, they were asked to name their favorite Republican president, each one including the eventual winner, Michael Steele, blurted out the name of Ronald Reagan without even a second’s pause to consider the name of Abraham Lincoln, who seemed to hold little appeal to the party’s rabid and increasingly Southern base, or even the hero of D-Day, Dwight Eisenhower, who presided over a remarkable era of American might.

—From Tear Down This Myth: The Right-Wing Distortion of the Reagan Legacy

Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Free Press. Copyright © 2009 Will Bunch

It was stunning in the 2009 debate between candidates to become chair of the Republican National Committee; as some may recall, all six hopefuls quickly named Reagan as their favorite ex-president, and not one even paid token lip-service to Lincoln. The simplistic answer would be racism – i.e., lack of excitement that Lincoln’s legacy was ending slavery – but I do not think that’s the reason, certainly not overtly. It’s just that Reagan, especially the mythologized version pushed by 21st Century GOPers, relates more to the battles the right is still fighting today, such as the unending “culture wars” against liberal elites and efforts to portray Democrats as weak on defense. That makes him a more potent and more useful symbol than Lincoln, whose remarkable nineteenth-century achievements are more abstract and are generally things that all Americans support.

3. Reagan is often portrayed as an arms hawk who brought down the Soviet Union through aggressive military spending. Is this a tenable claim? Does it take into account his arms control efforts?

The Cold War and Soviet relations are central to the Reagan legacy/myth. The conservative story line is (not surprisingly) a rather simple one: Reagan came in and spent billions on an arms race that bankrupted the Soviets, while his bellicose rhetoric – “evil empire” and “tear down this wall!” – cowed its leaders into allowing the collapse of the Iron Curtain. Reality is more complicated. For one thing, the U.S. arms build-up began under Jimmy Carter and a lot of the spending proved ultimately wasteful. Now that we have access to historical material from the Kremlin, we also know that our most bellicose moves strengthened hardliners at the expense of Soviet reformers. Reagan was right about one thing: Communism was a soon-to-fail economic system, as a new generation of USSR leaders led by Gorbachev also realized. This is why most people at the time, and most historians today, give the lion’s share of credit for ending the Cold War to Gorbachev and to the reform efforts that he initiated, such as glasnost and perestroika.

That said, Reagan deserves praise for realizing that Gorbachev was indeed a different kind of Soviet leader, and for encouraging his reforms. Likewise, people should realize that Reagan’s aversion to nuclear weapons was a deeply held, personal belief which motivated some major accomplishments in arms reduction at the tail end of his presidency. These aspects of the real Reagan – a willingness to negotiate with enemies at the right time, and his real concerns about nuclear weapons – are the parts of Reagan’s legacy that progressives should actually embrace and use in today’s political debates.

4. According to former Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill, former Vice President Cheney claimed during a cabinet meeting that “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.” How does deficit spending without consequences play in the Reagan legend?

This part of the Reagan legacy is so at odds with the 2010 message from Reagan-worshipping conservatives – especially the right-wing Tea Party faction – of fiscal discipline and deficit reduction that no one can figure out exactly what to do with it. I would argue that there are parallels between Reagan and Obama, in the sense that both presidents came into power during economic crises and both cut taxes and increased spending in their first year, leading to higher deficits. The one difference – and it’s an important one – is that Reagan’s increased spending was for the relatively wasteful area of defense (although it did lead to some job creation) while Obama is making an attempt to target more useful areas, such as infrastructure and alternative energy. The bottom line on Reaganomics is pretty bleak. Yearly deficits soared, and the overall national debt nearly tripled, from $930 billion to about $2.7 trillion, according to the Washington Post.

There was a short-term cost to this and a long-term cost. In the short term, Reagan’s profligate ways led to higher interest rates that slowed productively and eventually plunged the nation into a recession around 1990, leaving George H.W. Bush to deal with the mess. Policy makers had little room to maneuver in that 1990-91 recession because of the large deficits. Ultimately, both Bush 41 and Bill Clinton mounted a major effort to undo Reaganomics, including the breach of the “no new taxes” pledge that helped turn the senior Bush into a one-term president. Contrary to what Cheney said, deficits did matter, which is why the mythmaking and its influence in Bush 43’s reckless ways is so disturbing.

In the long-term sense, Reagan turned America from a creditor nation, which it had been since World War I, into a debtor nation. If you are unhappy about all the dollars that America owes to China today, that is a major element of the legacy of the president of whom we’re now erecting all these bronze statues. What’s more, many people – myself included – fault Reagan for promoting a kind of sunny, credit-card-driven consumerism that didn’t just hurt the nation’s wallet but led to unwise spending decisions and too much borrowing by everyday citizens. Do you remember “Wall Street,” with Gordon Gekko and “greed is good”? It’s not a coincidence that film was released at the zenith of the Reagan presidency.

5. Ronald Reagan signed the Convention Against Torture, and his Justice Department indicted and prosecuted a Texas sheriff for waterboarding. How can his views about torture be reconciled with the current Republican pro-torture dogma?

It’s important not to nominate Reagan for sainthood in the arena of human rights. His “Reagan Doctrine” in Central America, leaving the fight to anti-Communist thugs and death squads that the then-president called “the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers,” is arguably the gravest moral failing of his tenure. That said, back on U.S. soil, Reagan was far to the left of the 2010 Republican Party on issues such as torture. The convention that he signed in 1988 holds that there is no circumstance of any kind that permits torture, which certainly would include the 9/11 aftermath and related anti-terror efforts today.

But it goes even deeper than that. As I noted in an early 2010 blog post: “Reagan would not have approved of drone-fired missile attacks aimed at killing terrorists; as president, he several times rejected anti-terrorism operations for the sole reason that civilians would have been killed by collateral damage. In 1985, he surprised aides such as Pat Buchanan by ruling out a military response to a Beirut hijacking for fear of civilian casualties; Lou Cannon reported then in the Washington Post that Reagan called retaliation in which innocent civilians are killed “itself a terrorist act.” And the idea of trying terrorists in military tribunals as opposed to a civilian court of law? The Reagan administration was completely against that. Paul Bremer (yes, that Paul Bremer) said in 1987, “a major element of our strategy has been to delegitimize terrorists, to get society to see them for what they are — criminals — and to use democracy’s most potent tool, the rule of law, against them.”

It’s almost tragic – when you go back to the very recent history of the 1980s – when you realize how seriously an American consensus on human rights and the power of our criminal-justice justice system has been trashed by the modern conservative movement. It’s going to take a long time to get that back – although the words that Reagan and his aides left behind could help America get past this.

6. What is the most endearing thing you learned about Ronald Reagan in the process of researching and writing your book?

I mentioned above that his worries about the effect of so many nuclear weapons in the world were a sincere belief. One thing that I did not realize until I researched Tear Down This Myth was that in 1983, at Camp David, Reagan watched and was deeply moved by the nuclear war TV-movie sensation The Day After, which was perceived by most as a liberal and on some level anti-Reagan production. He wrote in his diary that the movie had strengthened his resolve to work with the Soviets on arms reduction, which he actually did after the arrival of Gorbachev. When he signed a major nuclear-reduction treaty in 1987, he telegraphed the producer of The Day After and said, “Don’t think that your movie had nothing to do with this, because it did.”