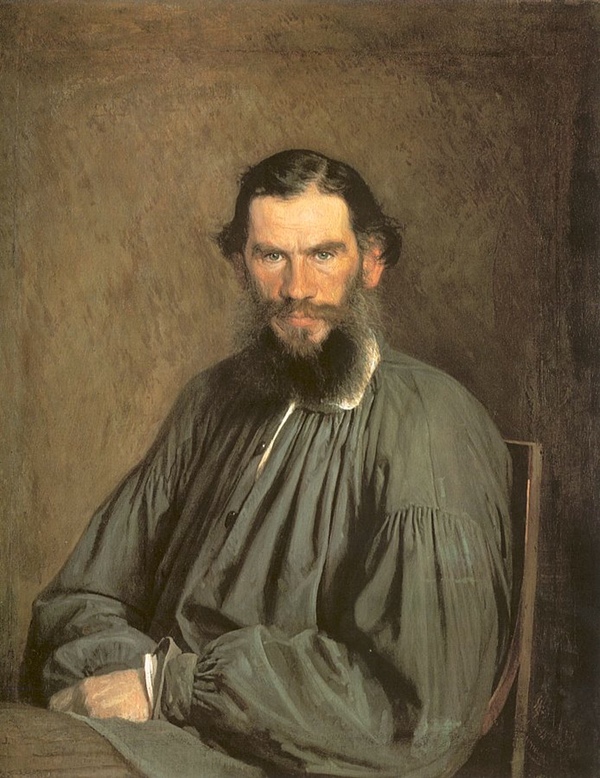

Ivan Kramskoi, Portrait of Count Lev Tolstoy (1873)

Ivan Kramskoi, Portrait of Count Lev Tolstoy (1873)

The longer I live–especially now when I clearly feel the approach of death–the more I feel moved to express what I feel more strongly than anything else, and what in my opinion is of immense importance, namely, what we call the renunciation of all opposition by force, which really simply means the doctrine of the law of love unperverted by sophistries. Love, or in other words the striving of men’s souls towards unity and the submissive behaviour to one another that results therefrom, represents the highest and indeed the only law of life, as every man knows and feels in the depths of his heart (and as we see most clearly in children), and knows until he becomes involved in the lying net of worldly thoughts. This law was announced by all the philosophies–Indian as well as Chinese, and Jewish, Greek and Roman. Most clearly, I think, was it announced by Christ, who said explicitly that on it hang all the Law and the Prophets. More than that, foreseeing the distortion that has hindered its recognition and may always hinder it, he specially indicated the danger of a misrepresentation that presents itself to men living by worldly interests–namely, that they may claim a right to defend their interests by force or, as he expressed it, to repay blow by blow and recover stolen property by force, etc., etc. He knew, as all reasonable men must do, that any employment of force is incompatible with love as the highest law of life, and that as soon as the use of force appears permissible even in a single case, the law itself is immediately negatived. The whole of Christian civilization, outwardly so splendid, has grown up on this strange and flagrant–partly intentional but chiefly unconscious–misunderstanding and contradiction. At bottom, however, the law of love is, and can be, no longer valid if defence by force is set up beside it. And if once the law of love is not valid, then there remains no law except the right of might. In that state Christendom has lived for 1,900 years. Certainly men have always let themselves be guided by force as the main principle of their social order. The difference between the Christian and all other nations is only this: that in Christianity the law of love had been more clearly and definitely given than in any other religion, and that its adherents solemnly recognized it. Yet despite this they deemed the use of force to be permissible, and based their lives on violence–so that the life of the Christian nations presents a greater contradiction between what they believe and the principle on which their lives are built: a contradiction between love which should pre scribe the law of conduct, and the employment of force, recognized under various forms–such as governments, courts of justice, and armies, which are accepted as necessary and esteemed. This contradiction increased with the development of the spiritual life of Christianity and in recent years has reached the utmost tension.

–Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, Letter to Mohandas K. Ghandi, Sep. 7, 1910 (English original)

A little more than a century ago, a Russian nobleman who was also one of the greatest novelists of his—or any other—age, took up his pen to write a letter to a young Indian lawyer then living in South Africa who had launched a movement against official racism. A short, powerful correspondence followed, fashioned in an English that is remarkably eloquent considering that it was not the native tongue of either writer. This correspondence can be read in a single sitting, in no more than thirty minutes, and doing so would be a rewarding process for anyone. But who could have imagined the influence that the Tolstoy-Gandhi dialogue would have for the coming century? Who could have imagined that those letters shuttling between Yasnaya Polyana and Johannesburg would ultimately provide moral inspiration and guidance to the American civil rights movement, half a century later? That they would have helped to propel one of the greatest social transformations in human history?

Count Tolstoy is a revered figure today, his works are published in all the languages of the world and inspire popular culture. In the last decades of his life, however, he was seen as a crazed eccentric in his homeland, and even as something of a threat. His advocacy of the renunciation of violence and his support of religious communities that the official Orthodox Church deemed heretical brought him into steady conflict with authority, and the conflict was acute precisely because his own moral authority seemed greater than theirs. Elif Batuman gives us an impressive feel for all of this in her fanciful The Murder of Tolstoy: A forensic investigation from the February 2009 Harper’s, another essential read.

Mohandas K. Gandhi was in many ways Tolstoy’s kindred spirit. A lawyer not a writer, a Hindu not a Christian, an Indian not a Russian. But the essence of Gandhi’s message was distinctly similar. And the differences helped demonstrate the universality of that message.

Listen to Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s Hymn of the Cherubim