Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour;

England hath need of thee: she is a fen

Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

Have forfeited their ancient English dower

Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart;

Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free,

So didst thou travel on life’s common way,

In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

The lowliest duties on herself did lay.

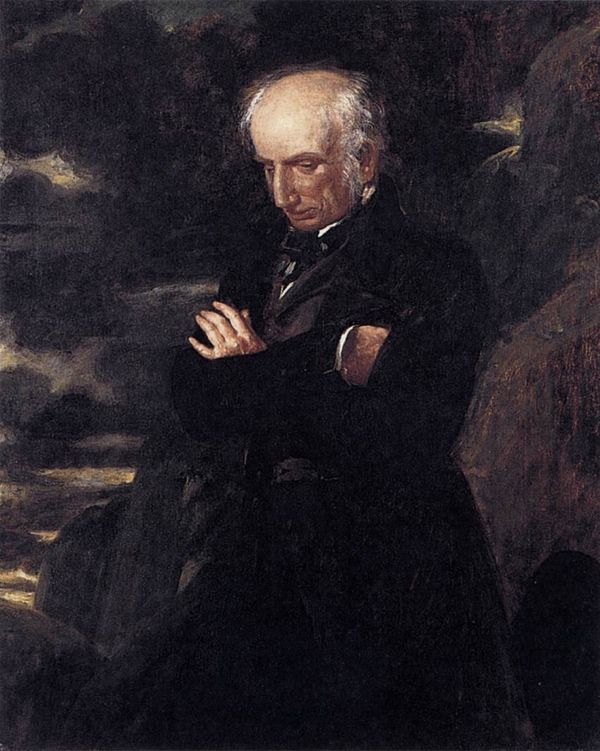

—William Wordsworth, London, 1802 first published in Poems, in Two Volumes (1807)

This poem might be one of the first manifestations of the conservative Wordsworth. It moves sharply away from the revolutionary Wordsworth of the prior decade, and it has distinctly nationalistic flashes (“ancient English dower/Of inward happiness”). It coincides with some dramatic changes in Wordsworth’s life–he came into an inheritance that enabled him to live comfortably, he married Mary Hutchinson, a childhood friend, and turned away from the radical, republican ideas of his college years. In Milton, Wordsworth sees a glorified vision of England’s past. True it doesn’t have the wealth of the nation’s emerging commercial supremacy. The nation’s wealth and power were rather of a spiritual sort—a unifying vision of England, in which the religious and the political fused. The golden days of Milton were, of course, far from golden by most measures. It was a time of immense turbulence, civil war, religious bigotry and violent death. How could this period be held up as an alternative to the age of Lord Nelson and William Pitt? Wordsworth’s criticism is focused, “we are selfish men,” he writes. He disdains a world in which the unbending rules of commerce govern life, in which the people grow steadily more detached from nature. Milton offers a different vision of England and her future. Still, Milton was an arch-republican, a friend and defender of the regicides and a man who placed as much value in the languages and literatures of the continent as of England. He is an improbable choice as a conservative nationalist.

But this is not the real Milton, it’s the Romanticist’s Milton. This poem strikes me as offering a vision of Milton which is remarkably like the one William Blake put forward. He is heroic and contrarian (and an early advocate of divorce, something which would have suited Wordsworth in 1802). Is it right to see in Milton such a strident nonconformist? Perhaps. In any event, he is a man of unquestionable religious sentiments but a moral vision distinct from the establishment’s. In that sense, Wordsworth sees a measure of himself reflected in history.

Listen to a performance of the Three Piano Pieces in E Flat Major, DV 946 (1828) by Franz Schubert. Andreas Staier plays a Viennese Hammerklavier from ca. 1825: