James Palmer, a British writer who lives in Beijing and has a fascination for all things Mongolian, has produced a captivating biography of Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, a Baltic nobleman who fought in the service of the Russian tsar in World War I. Following the Bolshevik Revolution, Ungern led a ragtag White army to capture Mongolia, where he styled himself the human manifestation of a Buddhist god of war. Mongolia would never be the same again. I put six questions to James Palmer.

1. Is it fair to say that Mongolia today is a sovereign and genuinely independent state because of Baron Ungern-Sternberg—because his machinations resulted in the country moving from the Chinese to the Soviet side of the Inner Asian spheres of influence, therefore allowing it to gain real independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union?

Yes. I believe that Ungern’s intervention, when he drove the Chinese out of Mongolia and then forced the Bolsheviks to come and take over the country as a result, probably was vital. I don’t want to take away from the achievements of Mongolians, of course. The Mongolians always fought the Chinese, and it’s possible, though I think pretty unlikely, that they could have resisted Chinese power by themselves, as they did in 1911. They seized the chance for real independence in 1990, as the USSR was falling apart. But I think Ungern did make a considerable difference, largely by accident. The Mongolians might have been able to drive out the Chinese warlords by themselves in 1921, but the Soviets would have been very reluctant to come in and help, because they were quite cautious about antagonizing the Chinese, and so Mongolia would have ended up, either in the twenties and thirties or, like Tibet and Xinjiang in 1949, retaken by China.

Russian rule meant horrendous slaughter and oppression in Mongolia, but the Mongolians always maintained their nominal autonomy. The Chinese, on the other hand, wanted to absorb and settle Mongolia, as they did to Inner Mongolia. The Mongolians are, according to Chinese nationalism, one of the “five peoples of China,” something which most Mongolians–like Tibetans and Uighur–would vigorously contest. They’d be in the same position as Xinjiang or Tibet now, watching Han settlers pour into their lands, and any attempts at revising nationalism or independence would be ruthlessly crushed.

As it was, they had the USSR backing them up, and by 1990 their independent status had enough international backing and support to make it impossible for revanchist Chinese ideas to get any grip. There’s still a desire among Chinese nationalists to take back Mongolia–I’ve heard “Mongolia used to be part of China!” many times–but it’s not, thankfully, a realistic one or one backed up by government policy, though it sparks plenty of paranoia and anti-Chinese prejudice in turn in modern Mongolia.

2. E.H. Carr famously ridiculed the “accident theory” of history which posits that something of such seeming inconsequence as the shape of Cleopatra’s nose might influence the course of human events, but your book seems to present us with a total nutcase who had undeniable influence on the course of a nation’s history. Is that a fair characterization?

The flipside to Carr’s objections is “Whig history,” or Hegelian determinism, the idea that history is moving unstoppably in a certain direction–like toward U.S. democracy, or Marxist utopia, or Prussian authoritarianism–and that the big forces of history aren’t affected by individuals. The idea is that if somebody shot Hitler in 1922, Germany would still inevitably have gone down the path of exterminationist anti-Semitism, and World War II would have worked out just the same. That’s just as ridiculous, I think. There are big social, cultural, and economic forces, naturally, but there’s also chance and contingency. Most of the time it probably doesn’t matter, and then sometimes it matters a lot. Ungern was undoubtedly one of those cases, a lonely, weird, sad man who found himself put in a position to affect the fate of millions.

But we can’t really know, because we only have the history we have. My fiancée’s in international relations, and one of the bad habits of that field is assuming that you can draw scientific laws from history–“countries with an income of $8000 or more have never stopped being democratic!,” that kind of thing. In its bastardized form you get nonsense like that Friedman line about two countries with a McDonald’s never having been to war with each other–an axiom that lasted all of seven years or so, until the United States bombed Serbia. But history is much too small a laboratory to draw firm conclusions of that kind.

3. How did the popular occultism of the early twentieth century influence Ungern-Sternberg and drive him towards his mission to Mongolia?

Popular occultism was fascinated by Asia. Much of it was second-hand Buddhist or Hindu ideas, like a lot of “New Age” thought today. The archetypal example is the hugely influential Helena Blavatsky, a Russian émigré and fantasist who travelled widely in Asia and created Theosophy, which to us looks like a ridiculous hodge-podge of Buddhism, Hinduism, Western occultism, pseudo-evolutionary theory, and wild dreams, but was popular and influential on various subcultures from the 1880s to the 1930s.

My name is surrounded with such hate and fear that no one can judge what is the truth and what is false, what is history and what myth.

–Baron Ungern-Sternberg, 1921

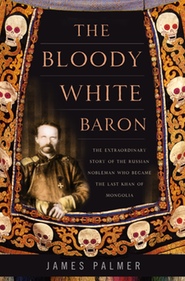

—From The Bloody White Baron: The Extraordinary Story of the Russian Nobleman Who Became the Last Khan of Mongolia

Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Basic Books. Copyright © 2009 James Palmer

Part of this was a wide popular fascination with Asia in Europe from the 1870s or so onwards, when the first translations of Asian sacred texts start being published, and you have Boston pastors travelling to Buddhist sites in India, for instance, on the slightly wry grounds that “in these days, when a large part of Boston prefers to consider itself Buddhist rather than Christian, I consider this pilgrimage to be my duty as a minister.” It’s very Orientalist, naturally; a mixture of fascination and fear. Asia is mysterious, powerful, and threatening. That was particularly acute in Russia when Ungern was growing up, because the Russians have always been torn between continents. They had that strong sense of their “Tartar” or “Mongol” heritage, which was both quite genuine–there’s lots of real Central Asian influence on Russian culture–and a hook for fantasies of escape, primitivism, and magic.

That fascination transferred to Germany later. There’s a marvellous line from one of D. H. Lawrence’s letters in the twenties, which naturally I found six months after the book was published–“the great leaning of the German spirit is once more eastwards, towards Russia, towards Tartary […] The positivity of our civilization has broken. The influences that come, come invisibly out of Tartary. So that all Germany reads Beasts, Men, and Gods [a “non-fiction” bestseller by the Polish writer Ferdinand Ossendowski about his adventures with Ungern] with a kind of fascination. Returning again to the fascination of the destructive East, that produced Atilla.”

4. You describe Ungern-Sternberg as a religious mystic who could be just as much at home in his native Lutheranism, in the Russian Orthodox church, or in Mongol-Tibetan Buddhism, but who was nonetheless a flaming anti-Semite. What produced these seemingly contradictory attitudes?

Religious mysticism has never been incompatible with ethnic or religious hatred; the Byzantine eremites and stylites, for instance, would often spout the vilest anti-Semitic bilge from their caves and pillars. It’s a little like the Tom Lehrer lines from National Brotherhood Week–“the Catholics hate the Protestants, and the Protestants hate the Catholics, and the Hindus hate the Muslims, and everybody hates the Jews.”

There wasn’t, of course, any native tradition of anti-Semitism in the Asian religions that fascinated Ungern, but he saw them through the lens of the European occult heritage, which has a long and ugly streak of anti-Semitism in it; it’s all over Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley, for instance. This is partially the common-or-garden prejudice of Europe, at the time, and partially because of the obsession with conspiracies and secret powers, which lent itself well to anti-Jewish paranoia and fantasies of ritual murder, especially when you had material like the “Protocols” being produced. If you look at the popularity of The Da Vinci Code today, it’s the same phenomenon, only with Catholicism swapped out for Judaism (tapping on a very old and nasty legacy of fantasies about Catholicism in Protestant countries, but that’s another issue.)

The occult tradition also misappropriated several Jewish traditions, like qabala, and so, I think, there was some kind of need to discredit the people they’d stolen from. Then there’s that peculiar alliance between occultism and the right, because the right at the time was all about elitism, about the need for a small group that could control the wild masses, and that slotted in very well with occult thinking, which was all about special powers and secret groups of initiates. It’s not occult if everybody knows about it, after all.

5. Casual cruelty has been described by some historians as an effective strategy in the hands of the Mongols who swept across the Steppe to create an empire, but you see in it part of Ungern-Sternberg’s unmaking. Why?

I don’t know if cruelty is necessarily part of Steppe life–I’ve seen children tormenting goats, but kids are rotten everywhere. A certain ruthlessness definitely is, and a comfort with bloodshed and violence that you have to have in such a tough environment. The upside of that is a real dedication to hospitality and life; Mongolians are extraordinarily generous to strangers and guests, because it’s that code of hospitality that’s allowed them to survive a hard place for so long.

Steppe ruthlessness benefitted the Mongol armies in two ways. The first was that Steppe-raised warriors, unlike agriculturalists, were easy about killing, which mattered a lot, particularly in the days when most of your killing was done hand-to-hand. They could butcher people as easily as sheep. The second is that they were able to use that ruthlessness–that willingness to level a city and slaughter its inhabitants–to spread fear among their enemies, and manipulate that fear into forcing surrenders before they even had to fight, ideally. As long as you lay down and rolled over as soon as they showed up, the Mongols generally wouldn’t hurt you. If you fought, they’d kill everybody. And they were masters at spreading that fear through rumor, too. But the Mongol empires themselves, once they were established, weren’t especially cruel by the standards of the day, nor particularly racist; people could be absorbed into the Mongol armies very easily.

Ungern and his men, on the other hand, had an unfocused, chaotic sadism that took itself out as often on their own side and on random civilians as on their enemy, combined with, in the case of many of his men, a contempt for the people they found themselves among. Ironically, the Chinese they drove out of Mongolia had behaved in a very similar way. They were trying to build popular support to raise an army and support themselves, and you can’t do that when you’re torturing strangers snatched off the street. It was like the Germans in Ukraine in World War II, where they utterly destroyed the initially strong local support–for a brief time they were seen as liberators from Stalinism–with their own stupid bastardry and racism.

Looking at it utterly cold-heartedly, you can pull off being utterly ruthless as a tactic when you have the force to back you up, and can do it as thoroughly as the Mongols or the Romans did–the Romans never hesitated to kill or enslave “barbarians” in the tens of thousands. But random rape, pillage, and torture just leaves the people hating you all the more. As for Ungern’s own men, when times were relatively good his cruelty kept them bound to him. When things went bad, though, it wasn’t, “Hey, boss, can we have a word?” It was a midnight assassination attempt.

6. Why did the Bolsheviks feel so threatened by Ungern-Sternberg and his efforts to revive a truly independent Mongolia?

Well, Ungern technically didn’t want an independent Mongolia as such; he wanted a reunified Qing empire with Mongolia as a part and China as the centre–an idea about as popular in Mongolia as suggesting going back to British rule would have been in India in 1955. He kept somewhat shtum about this while he was in Mongolia, since his Mongolian allies very much were fighting for their own autonomy.

The Bolsheviks didn’t particularly care about Mongolia–the Mongolian Communist representatives were ignored until Ungern came along. What they cared about was the threat of a White-backed power on their borders. This was at the end of the Civil War, after all, which had killed millions of Russians and wrecked half the country. Any chance of that being revived–and there were still hundreds of thousands of Whites in exile, after all–had to be crushed. Plus Ungern’s actions in Siberia, where he’d run his own little mad fiefdom and operated death camps that murdered Red prisoners, had made him a particular bogeyman. You had to really go above and beyond to stand out as a sadistic lunatic in the context of the Russian Civil War, but he went that extra mile. That meant that defeating him was always going to be a propaganda coup; he was a kind of Osama bin Laden figure for the Bolsheviks.