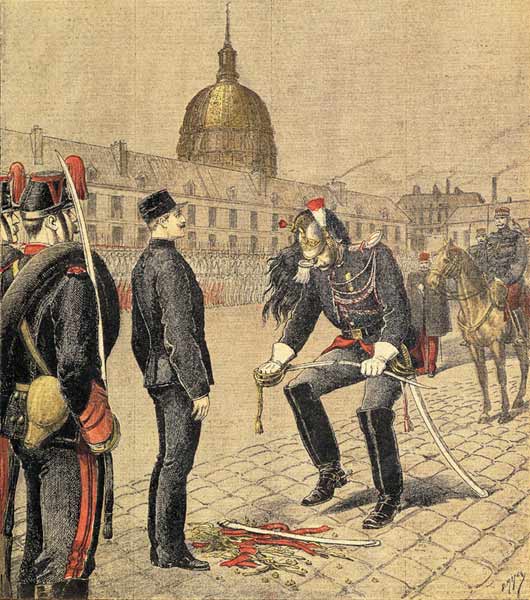

In a superior review essay in the weekend’s Financial Times, Donald Morrison considers the historical shadow of the affaire Dreyfus. Of the defining role of this scandal in modern French history, there can be no doubt. But did it have ramifications on the global stage and does it still have something to say to us today? Both the reviewer and the authors under review seem to agree on the answers to those questions.

In France, the original case still incites debate. There are people who still believe that Dreyfus was guilty, or that national preservation excused his treatment. Those who celebrate his innocence fear that the kind of state-sponsored injustice he endured has not been eradicated, and that the clubby world of French officialdom continues to act arbitrarily, secretly and sometimes illegally without penalty. For both sides, the Dreyfus case was a watershed in modern French history. The divisions it created resurface periodically – in the debates over wartime collaboration, France’s struggles in Vietnam and Algeria, anti-Semitism, official corruption, immigration and other failures of governance. Though it unfolded more than a century ago, the captain’s ordeal has since inspired more than two dozen feature films, documentaries and television dramas, as well as hundreds of books. The latest batch includes a handful by French authors aimed at France’s seemingly insatiable Dreyfus market as well as works by non-French authors continuing to apply its lessons to their own contemporary controversies.

Best among the latter group is American lawyer and novelist Louis Begley’s Why the Dreyfus Affair Matters, a slim but powerful denunciation of Bush administration missteps in the fight against terrorism. Begley likens Dreyfus to the 800 or so “enemy combatants” dispatched to the notorious US military lock-up at Guantánamo, nearly all without trial or even charges. Like the captain, Begley notes, the detainees were for the most part denied basic rights, held in harsh conditions and ultimately found to be innocent (nearly 600 have been released). Begley salutes the journalists, lawyers and judges who fought against “torture and kangaroo trials” to free them: “They have redeemed the honour of the nation,” he writes.

The developments surrounding Dreyfus, incidentally, make an interesting contrast with the discussion of Nietzsche’s analysis of German conservatism of the Gründerjahre (1870-90), which I discussed in connection with the recent Helmut Schmidt-Fritz Stern book this weekend. In the wake of France’s defeat and Germany’s victory in 1871, both countries saw a spike in extreme nationalism, militarism, religiosity, and anti-Semitism. The difference between the two was, as the discerning Fritz Stern notes, that France was able to muster powerful voices for republican values, an open society, and fidelity to justice over politics.

Although the comparison of the Guantánamo prisoners to Captain Dreyfus may be somewhat attenuated, there is still much to it. The prisoners have been harshly vilified by government spokesmen. When, after examination of the actual evidence, it appears that there was little if any justification for the vilification, that fact is simply glossed over. A handful of these prisoners truly are guilty of despicable crimes. But perhaps eighty per cent of them had no business being held in the first place. The Bush Administration made a scapegoat of them and brutalized them, with far more venom and political malice than Captain Dreyfus ever experienced. And the Bush Administration’s commitment to justice can best be summed up in the words that Jim Haynes–who as general counsel to the Department of Defense oversaw the proposed military commissions–reportedly put to chief prosecutor Col. Moe Davis:

“Wait a minute, we can’t have acquittals. If we’ve been holding these guys for so long, how can we explain letting them get off? . . . We’ve got to have convictions.”

But outside of a handful of lawyers and human rights activists, now themselves the targets of a McCarthyite smear campaign, no actors on the political stage in Washington see any advantage in rallying to the cause of the Gitmo prisoners. This is demonstrated by the infamous 90-6 vote in an overwhelmingly Democratic senate to block funding for the Obama initiative to close Guantánamo. America does not want to confront the reality of its own conduct. Where today is the voice of a Clemenceau or Zola on the American political stage?

One of the key lessons of the Dreyfus experience is that in times of perceived national security crisis, the justice process often suffers in the face of perceived political exigency, and few political leaders have the fortitude to defend it. Justice too often is itself denounced as a weakness or luxury that the state cannot afford in such circumstances. History teaches another lesson: true justice, wielded forcefully, is no liability, but rather a powerful weapon in the hands of any democratic state.