By the time Sandberg left Google, there were no more doubts about that company’s ability to turn Web traffic into cash. The achievement was so emphatic that Sandberg and her colleagues used to worry about the other extreme, which they called “success disaster,” a fairly common fate among tech start-ups. “You can’t underestimate the intensity and complexity of being a leader in an organization that’s undergoing hypergrowth,” says Adam Freed, Google’s former director of product management and one of Sandberg’s friends from her Harvard days. “Sheryl had to make decisions very quickly based on reasonable but imperfect data. The annals of business history, especially in Silicon Valley, are littered with the wreckage of companies that started to experience hypergrowth and mismanaged it. But Sheryl was able to see way down the highway, very quickly, to judge what the outcomes of her decisions would be.” Whether you call it “scaling the company” or “managing hypergrowth,” Sandberg is one of the few executives on Earth with a demonstrated knack for it. —“What She Saw at the Revolution,” Kevin Conley, Vogue

What does it all mean: photos of German automobiles smashing simulated animals to bits;

ancient organisms lavishly captured;

evil cat terrifies inbred canine–the horrifying videographic evidence!

Modern intellectuals…tend to be less concerned with a knowledge of the canon, and more fixated on these issues of the day, and often seek a mass audience in our mass democracy. We even have a subset of intellectuals who are particularly involved in public affairs, either inside or outside of government. Historian Russell Jacoby labeled them “public intellectuals,” usually well-known, well-educated generalists who can speak or write about most subjects, injecting their own overarching worldviews into their pronouncements. These public intellectuals are, in many ways, the opinion-shapers of the growing educated class. Some are academics; others are writers, critics, or journalists; most have gone through a few elite universities, at least as undergraduates; all try to contend with social and political reality at the conceptual level, so as to offer a perspective that provides some coherence to politics and current events. Of course, the reality of their existence is not always so high-minded: They also form a community of intellectuals, with its own, often low-minded, politics and culture, and its own complex connections to the popular culture and the rough-and-tumble of American politics. —“Bush, Obama, and the Intellectuals,” Tevi Troy, National Affairs

Steve Jobs will buy your perversions;

Simon Cowell will cover your abortion;

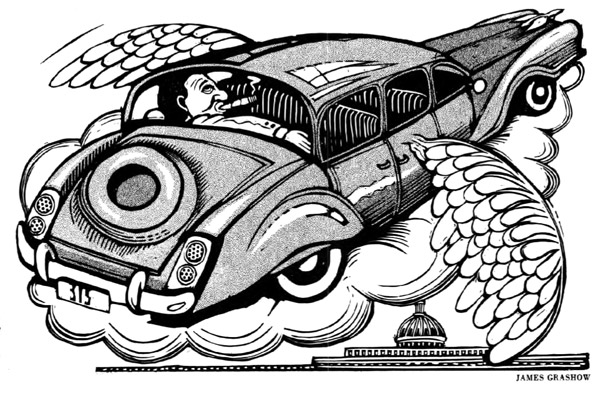

Al Gore vs. the volcano

Sheikh wears red, draping the end of her soft cotton sari demurely over her head. I have come to interview her specifically, and she is supposed to be the center of attention, but as we begin to talk she tries to defer to everyone else. She doesn’t want to sit on the chair because the rest of the onlookers—many of them men—are sitting on a bench or on the ground, and she feels uncomfortable with the higher status that the chair gives her, though it’s no taller than the benches. Everyone insists she sit on the chair. So she abandons the stool and sits on the chair, dropping her flip-flops on the ground and curling her feet behind the bottom rung. The darkness blots out the external world and everything outside of the circle of light coming from Sheikh’s doorway. We sit in a broad, well-swept mud courtyard. Besides Sheikh, our group includes a savvy male translator from Kolkata, a female local guide, two dogs, a goat nibbling discarded clothes, and around 20 nosy interlopers from her family and the village. A duck arrives late, loudly interrupting with surreal quacking before waddling into the darkness. —“A Distribution of Chairs,” Anrica Deb, The Morning News

Right wing doctors will one day rule the world;

if it’s all fiction, do you still like Ike?

no, France, we will not let your pedophile go! (unless we do–he is famous, after all)