Il n’y a point de plus cruelle tyrannie que celle que l’on exerce à l’ombre des lois et avec les couleurs de la justice: lorsqu’on va, pour ainsi dire, noyer des malheureux sur la planche même sur laquelle ils s’étoient sauvés.

Et comme il n’est jamais arrivé qu’un tyran ait manqué d’instruments de sa tyrannie. Tibère trouva toujours des juges prêts à condamner autant de gens qu’il en put soupçonner. Du temps de la république, le sénat, qui ne jugeoit point en corps les affairs des particuliers, connoissoit, par une délégation du peuple, des crimes qu’on imputoit aux alliés. Tibère lui renvoya de même le jugement de tout ce qui s’appeloit crime de lèse-majesté contre lui. Ce corps tomba dans un état de bassesse qui ne peut s’exprimer; les sénateurs alloient au-devant de la servitude; sous le faveur de Séjan, les plus illustres d’entre eux faisoient le métier de délateurs.

No tyranny is more cruel than that which is practiced in the shadow of the law and with the trappings of justice: that is, one would drown the unfortunate by the very plank by which he would hope to be saved.

Moreover, no tyrant ever lacks the instruments necessary to his tyranny. Tiberius always found the judge who was prepared to sentence any person of whom he had the slightest suspicion. In the time of the republic the senate, which did not as a body pass judgment on specific transactions, nevertheless, through a delegation of the people, took cognizance of crimes that were imputed to allies. In a like manner, Tiberius referred to this body the adjudication of all crimes which he considered an act of offense against his person. The senate then fell into a state of utter degradation such as can scarce be described; the senators themselves led the processional into their own enslavement. Under the patronage of Sejanus, the best known among them competed to be informers for the emperor.

–Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence, ch. xiv (1734) contained in Œuvres complètes, vol. ii, p. 144 (R. Caillois ed. 1951)(S.H. transl.)

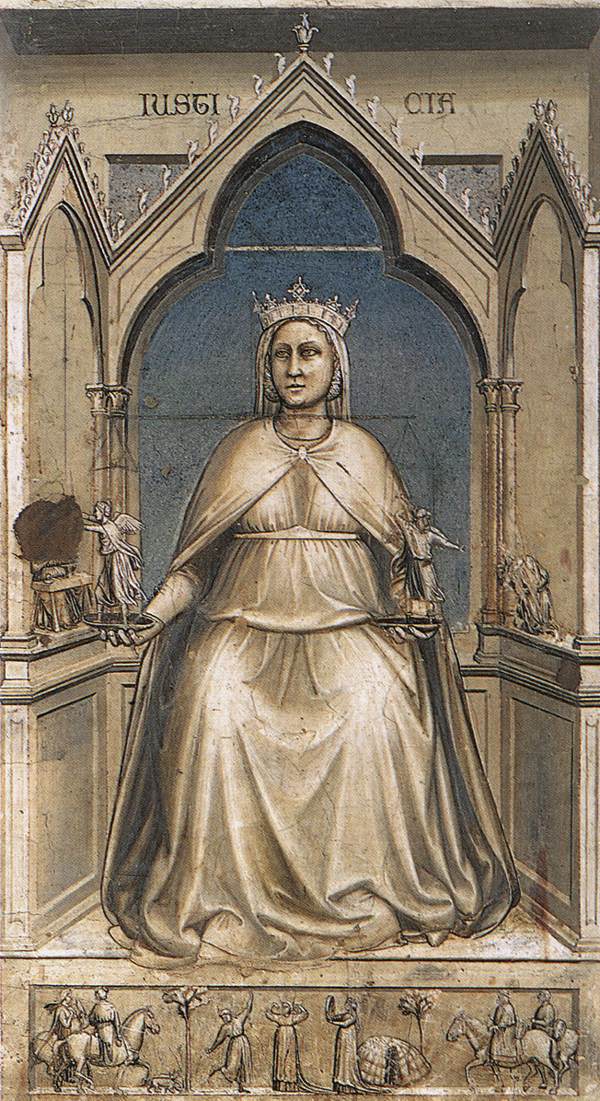

The American Founding Fathers were influenced by the lessons they drew from a study of antiquity and particularly helped in this process by Montesquieu and his essay of the rise and collapse of liberty in Rome. In Montesquieu’s study of Tiberius, he reflects how the institutions of government were steadily corrupted by those who sought the favor of the emperor. Judges convicted and sentenced anyone of whom Tiberius grew suspicious; senators vied with one another in denouncing their rivals to him. This reflects the weakness of human nature in the face of power, but Montesquieu focuses on how it causes the disintegration of the justice system. There is something particularly pernicious about a situation in which the outer trappings of justice exist, but the substance has been replaced with a craven homage to the power of the executive. Montesquieu drew on Tactitus for his examples, but subsequent human history can recount many others. In 1946, for instance, just this concern about the warping of justice by a tyrannical spirit led to a decision, controversial at the time it was formed, to put justice ministry officials, prosecutors and judges on trial for their complicity in crimes against humanity under the Nazi regime. Powerful as that example was, others can be cited in societies which retain a better semblance of justice. As for example, in the just-past Bush Administration, in which lawyers of the Justice Department issued memoranda approving torture with presidential authority, authorized warrantless surveillance, launched bogus prosecutions of political rivals and indulged the bribing of foreign government officials in commercial dealings, all in the name of executive power elevated above the law, but given the benefit of formal legality.

Listen to Claudio Arrau perform Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, op. 73 (1809-11). In the English-speaking world, this work carries the title “The Emperor,” a reference to Napoleon, though that was not of Beethoven’s choosing. Beethoven welcomed and admired Napoleon when he first emerged on the stage of world politics; he viewed him as the herald of a new era of democracy and civil rights. But when Napoleon crowned himself emperor, Beethoven viewed this as an act of betrayal. Beethoven’s attitude towards imperial assumptions of power was mocking, not magnifying.