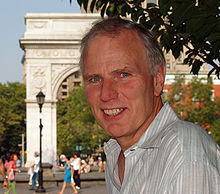

Last week the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, NYU law professor Philip G. Alston, issued a study on targeted killings in which he exhaustively reviewed and critiqued the United States’s use of drones, particularly in Afghanistan and Pakistan. I put six questions to Prof. Alston about his conclusions.

1. In your report, you specifically challenge the American government’s decision to allow the CIA to wage drone warfare, calling it the “greatest challenge” to the principle of compliance with the law of armed conflict. Why is drone warfare by the CIA inherently more troubling than the use of drones by the uniformed military, which also relies heavily on civilian contractors throughout the process?

Let me start with the boring part–a legal definition of a targeted killing. It is the intentional, premeditated, and deliberate use of lethal force, by a state or its agents acting under color of law, or by an organized armed group in armed conflict, against a specific individual who is not in the perpetrator’s custody. A good example is when the United States uses a drone in Pakistan’s tribal regions to monitor a particular suspect for several weeks, information is gathered on his comings and goings, and the suspect is then targeted and killed by an armed drone. Both the U.S. military and the CIA have carried out such targeted killings in recent years. It’s no secret that over the years there have been significant problems with U.S. military compliance with the laws of war, and related transparency and accountability issues. But the CIA almost makes the military look good. Because it shrouds its operations in secrecy, it has to reject out of hand the international law requirement that there must be at least some minimal accountability for such targeted killings.

Since armed conflict is the only context in which a targeted killing operation is likely to be legal, we’re talking about the laws of war. Those laws do not prohibit an intelligence agency like the CIA from carrying out targeted killings, provided it complies with the relevant international rules. Those rules require, not surprisingly when it’s a matter of being able to kill someone in a foreign country, that all such killings be legally justified, that we know the justification, and that there are effective mechanisms for investigation, prosecution, and punishment if laws are violated. The CIA’s response to these obligations has been very revealing. On the one hand, its spokepersons have confirmed the total secrecy and thus unaccountability of the program by insisting that they can neither confirm nor deny that it even exists. On the other hand, they have gone to great lengths to issue unattributable assurances, widely quoted in the media, both that there is extensive domestic accountability and that civilian casualties have been minimal. In essence, it’s a “you can trust us” response, from an agency with a less than stellar track record in such matters.

We know–the world knows–that the CIA has a program pursuant to which it uses drones to commit targeted killings in other countries. These killings occur primarily in Pakistan, but also in other countries, including Yemen. The CIA has killed hundreds of people, including civilians. But not even the American public, let alone the international community, knows when and where the CIA is authorized to kill, the criteria for individuals who may be killed, how the CIA insures killings are legal, and what follow-up there is when civilians are illegally killed. It follows that the international law requirements of transparency and accountability are comprehensively violated.

There are similar problems with the military, especially if Special Operations forces are used, because these forces also often conduct operations in secrecy. But unlike the CIA, there is at least the potential in U.S. military operations for there to be public accountability. On May 30, 2010, for example, the U.S. military in Afghanistan released a report on the February killing of 23 civilians in Uruzgan. The civilians were killed because of erroneous intelligence from surveillance drone operators, and the report urged the U.S. Air Force to open its own investigation. Senior officers involved were disciplined and additional training ordered. We’ll have to wait and see the outcome of the Air Force investigation, but, at least in this case, there appears to be a basic commitment to meeting accountability obligations, including on the battlefield. In contrast, the CIA is determined to remain unaccountable and thus has no place in running a program allowing it to kill people.

2. The United States has charged child warrior Omar Khadr with “homicide in violation of the law of war” in military commission proceedings in Guantánamo. If the United States is correct on the proposition (and I understand that you disagree with it) that it is a war crime for an unprivileged combatant to use lethal force in wartime, does that not mean that CIA officers and civilian contractors working with them might be equally chargeable with war crimes?

You’re right, I do disagree with the proposition that it is a war crime for an unprivileged combatant (or “unprivileged belligerent” as the laws of war term it) to merely “participate” in armed conflict. That’s because the laws of war don’t criminalize a person based solely on his status, such as being an unprivileged belligerent. Instead, they focus on conduct – i.e., whether or not the person’s activities comply with the law of war rules. But the difference is that unlike members of a state’s armed forces, civilians, including CIA agents, do not have immunity from prosecution for domestic law violations. So a CIA agent or a civilian contractor who uses lethal force in compliance with all the restrictions of the laws of war has not committed a war crime, but that person can be prosecuted for murder or homicide under U.S. law, or the law of the state in which the killing occurred (unless a government negotiates immunity under domestic law, as the U.S. has done in Afghanistan for its officials and contractors operating there).

In contrast to the law of war rules, the original military commission rules included as “murder in violation of the laws of war” the use of lethal force by a person who does not meet the “requirements for lawful combatancy.” It has been reported that these rules were changed because the State Department recognized that this approach–predicated on the status of a person, not their conduct–would, if applied to CIA agents in the drone killing program, have created the risk that they could be prosecuted for “war crimes.”

Of course, calling something a war crime doesn’t make it so–the question is whether it is recognized as such under international law–and your question raises a broader concern and reflects the deeply disturbing approach of the United States to the laws of war since 9/11. The U.S. has put forward the novel theory of a brand new “law of 9/11” under which it can sidestep the laws of war or re-interpret them when it suits. This approach is no doubt appealing and convenient in the short term. But it will inevitably return to bite the U.S., and will undermine the international legal framework on which the U.S. relies in so many other contexts. In this particular instance, if the U.S. were to insist that use of lethal force in an armed conflict by a civilian who is a citizen of another country is a “war crime” just because that person is a civilian, it won’t have a leg to stand on if another state prosecutes a CIA agent involved in the drone killing program on exactly the same grounds.

More broadly, in asserting an ever-expanding “right” to target and kill individuals anywhere in the world, the U.S. completely undermines the rules it has helped craft over half a century designed to prevent other states from carrying out extrajudicial killings. The rules the U.S. asserts today will surely be invoked by Russia, China, Iran, or any number of other countries tomorrow.

3. The Washington Post quotes an anonymous American official responding to your report who claims that the precision of the drone program is “unsurpassed in the history of human conflict,” and that there is no better technique to be used to deal with the threat presented by Al Qaeda and the Taliban. He claims that “absolute necessity” and the doctrine of self-defense justify the use of drones in the way the Obama Administration has used them. How do you react to this?

The official is right in underscoring the accuracy of the drone missiles. I don’t contest that, and I understand why the administration wants to be able to use them. If they are used correctly, and in the context of an armed conflict, I don’t have a problem. My concerns are (i) they are sometimes used, unjustifiably, outside conflict zones; (ii) when they are used by the CIA they violate the rules relating to international accountability that the U.S. has very often demanded be observed by other governments; and (iii) the U.S. government has put forward legal rationales, such as the doctrine of self-defense, which are self-serving and unsupported by international law.

In terms of legal rationales, it is symptomatic that the U.S. pointedly refused to provide any response to my report to the UN Human Rights Council beyond the equivalent of “interesting report, look forward to reading it one day.” But at the same time Secretary of Defense Gates and anonymous government officials have been busy providing the media with unverifiable assertions of legality and accountability.

You are right that the administration has put forward a “law of 9/11” self-defense justification, which would permit it to use force in the territory of other countries on the basis that it is in an armed conflict with al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and “associated forces.” The latter group, of course, is undefined and open-ended. This interpretation of the right to self-defence is so malleable and expansive that it threatens to destroy the prohibition on the use of armed force contained in the United Nations Charter. If other states were to use this justification for the killing of those they deemed to be terrorists, the result would be chaos.

States can, of course, defend themselves. They can do so in response to an armed attack or one that is real and imminent. That use of force has to be both necessary and proportionate. But the U.S. position is, in essence, that nine years after 9/11 it is still responding to a real and imminent attack and will probably continue to do so for years to come. Even if we were to accept that the U.S. is able to do whatever, whenever, because it is responding to somewhat distant armed attacks (which I don’t accept), that doesn’t give the U.S. a carte blanche to target and kill whomever it deems to be a terrorist or an enemy. Even if it is acting in self-defense, the targeting of a particular person still needs to comply with the requirements of the laws of war and human rights law. The United States seems to want to marginalize or even eliminate the relevance of human rights law and the laws of war in situations that it claims are governed by the self-defence rationale.

4. You chide the United States for failing to provide the guidelines for its use of drones, but the Obama Administration refers those who question its guidelines to a speech that Harold Koh delivered to the American Society for International Law. What issues did Koh fail to address?

The speech by the State Department’s Legal Adviser, Harold Koh, to the ASIL is an important starting point. It’s clear that at least some in the administration are grappling with the question of how to square the targeted killing policy with its expressed commitment to international law. That is the good news. The bad news is that all too little seems really to have changed in practice since the Bush Administration put forward claims that were excessively broad. I remain hopeful that the administration will make good on its international law commitments, but there is a way to go.

Harold Koh’s speech justified targeted killings on the basis of the right to self-defense, as well as on the laws of war. He outlined both legal frameworks, but addressed none of the questions about dangerous over-reach that I and many others have identified. In a speech which assiduously made no mention of the CIA, he didn’t address, for example, the scope of the armed conflict in which the United States asserts it is engaged, the criteria for individuals who may be targeted and killed, the existence of any substantive or procedural safeguards to ensure the legality and accuracy of killings, or the existence of accountability mechanisms. In fighting to promote the rule of law, the United States needs also to follow it.

5. You also discuss the death in detention of three prisoners in Guantánamo on June 9, 2006. You note that the U.S. claims that the pathologists conducting autopsies for the families of the deceased “did not submit an official request” to see the underlying reports or the missing body parts removed by American pathologists. As we have reported in Harper’s, however, a request was made on behalf of the pathologists by the human-rights group Alkarama. In fact we published the request, confirmed that it was received, and examined correspondence in which the U.S. military pathologist indicated he was under instruction not to cooperate with his foreign colleagues. How do these facts affect your assessment of the case?

On February 22, 2010, I wrote to the United States about the deaths of Salah Ahmed Al-Salami, Mani Shaman al-Utaybi, and Yasser Talal Al-Zahrani. I asked the U.S. to respond to allegations that the three men may not have committed suicide and to explain whether thorough and independent investigations subsequently took place. I also asked for the results of any investigations, and an explanation as to why certain body parts were removed from the three men by military pathologists, and why those parts and the first autopsy reports were not provided to independent pathologists as requested by the families of the deceased men.

In replying to me on March 12, 2010, the Government stated that thorough investigations had been conducted, and that it was found that each of the three men committed suicide. The United States also stated that the Government did “not receive an official request by the independent pathologists to examine the retained parts,” and implied that this was why the parts had not been provided.

Since I published my report, I have seen evidence suggesting that, in fact, the retained body parts were requested by the families, including a June 29, 2006 letter from the organisation assisting one of the deceased men, requesting the retained parts and the first autopsies. The information provided to me states that the letter was also sent to the U.S. embassy in Berne, but that it was never replied to.

The apparent discrepancy between the government’s assertion that an official request was never received, and evidence that formal written requests were in fact made, is very concerning. Lack of access to the retained body parts clearly impedes the ability of the independent pathologists to conduct meaningful autopsies, since such parts would be key evidence in a hanging-death autopsy. The U.S. should promptly respond to requests for the retained parts, original autopsy reports, and other relevant information. It should also clarify whether it received the earlier apparent requests, and if it did, why no action was taken on them at the time.

6. Physicians for Human Rights has now issued a report presenting the case that healthcare professionals working for the CIA may have been conducting human experimentation in connection with detention operations and interrogations like those that must have been conducted at Guantánamo’s Camp No. Do you intend to investigate these allegations?

The allegations contained in the Physicians for Human Rights report released on June 6, 2010 are extremely concerning. While the United States acknowledged some time ago that waterboarding and other forms of what the Obama Administration agrees are torture were carried out against detainees by U.S. officials, this report goes further and alleges that health professionals were involved in “research and experimentation” on those in U.S. custody. It alleges that medical professionals, for example, monitored detainees while they were being waterboarded, and that the CIA waterboarding “technique” was modified according to the information gathered by the medical professionals. Such claims raise important questions about whether the medical professionals violated U.S. domestic or international law prohibitions against non-consensual human subject experimentation. While I cannot assess the accuracy of these claims, they clearly need to be the subject of a full, independent inquiry, which would also consider whether there is a basis for criminal prosecutions for torture, killings, or other violations.