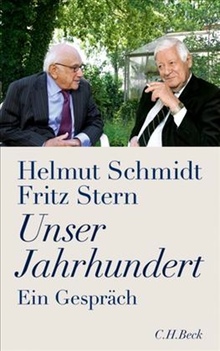

With the kind permission of C.H. Beck Verlag, former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt, and Columbia University historian Fritz Stern, we present here the second in a series of excerpts from the bestselling book Unser Jahrhundert – Ein Gespräch, in an original English translation.

ii. remembering golda meir and yitzhak rabin

stern: Israel or Bismarck?

schmidt: We want to discuss one of them, but we have to come back to the other subject. An unedifying subject.

stern: One doesn’t make any friends with this subject–neither in America nor in Israel.

schmidt: And not in Germany either. And I have little desire in my days of advanced age to make new enemies. But once we were received with open arms in Israel. That was in the sixties. In 1966, Loki and I undertook our first trip to Israel — we had been invited by grandmother.

stern: Which grandmother?

schmidt: Golda Meir. She was roughly twenty years older than we were. That’s why Loki and I called her grandmother.

stern: 1966. So it was before the war, the famous Six Day War.

schmidt: Before the war, yes. In the seventies, our relationship with Israel grew more difficult, although there were exceptions; with Moshe Dayan, for instance, the hero of the Six Day War, I was on the best terms.

stern: Overall, I would say that the Israelis themselves were less critical towards the Germans than the American Jews were. Not all of them, but many, especially the right-wing American Jews, had an enormous resentment. And they still have it.

schmidt: Yes, and without the American Jews the settlements on the West Bank would never have come about the way they did.

stern: Without part of the American Jews.

schmidt: That is, however, not my personal experience. A friend explained this to me a few years ago, in the course of a discussion about the settlements on the West Bank. You just have to look, he said, they’re all young people who were born and brought up in the Bronx.

stern: That’s probably a great exaggeration. Certainly there are some who went over and became settlers on the West Bank, but it is more likely a somewhat smaller number.

schmidt: No matter how many, Fritz, the fact is that Israel could never have pursued such an offensive policy in the Middle East without the complete cover that America provided in the last thirty years.

stern: We spoke about this at length yesterday.

schmidt: What can the Israelis do? They have gotten themselves on the wrong track, and in the process they’ve created one of the few possibly insoluable problems in the world today.

stern: This is a great tragedy. I am very concerned about the future of Israel when I think about its own policies.

schmidt: For more than forty years the world has known that a solution is only possible on the basis of two states. Since 1968, this recognition has been shared by all governments of the world, more or less, with the sole exception of Israel. In the meantime a half million Israelis live on the West Bank and in East Jerusalem.

stern: Yes, and the conditions on the West Bank are deplorable, I mean how the Arabs are treated.

schmidt: The so-called wall, which runs for many kilometers around each settlement without taking the Arab population into consideration, stands outside of the official territory of the state of Israel.

stern: And it’s neither justifiable under international law nor humane. There have of course been efforts to come to a two-state solution. I took Yitzhak Rabin seriously, his efforts amounted to a proper approach. Then he was killed by a fanatic. And aside from him there were then and there are today important Israeli politicians, organizations, and individuals who are engaged for peace and a reasonable solution. The Israel of the hardliners is not the entire country.

schmidt: In the Oslo process Rabin set course for the two-state solution. The fate of the settlements was, however, set aside for the moment.

stern: I believe that Rabin hoped that compromises could be made. His model would have been: we will give up some settlements, and in exchange for those that we’re keeping, we’ll give you, the Arabs, some more land elsewhere. There were and are still today some organizations in Israel that are absolutely committed to the return of this land. I knew an Israeli general by the name of Tal. General Tal was called the Israeli Rommel because he was a major tank commander—in 1967 and even more significantly in 1973 in the Yom Kippur War. It was he who pressed to the banks of the Suez Canal and who then signed the cease-fire agreement on the Nile. Three years later I visited him. He showed me pictures of the ceasefire: he was standing on his tank, surrounded by other tanks. And then he suddenly said: “We won a great victory, but I have to say this: We have to give it all back.”

schmidt: Some day, sooner or later, or–

stern: Indeed, not today. But also not in some uncertain distant future. “We have to give it all back.” And then he said–the discussion occurred in the Ministry of Defense–“Here in this house I am an exception.”

schmidt: Later I suspect Moshe Dayan was of a similar opinion.

stern: And later he said, and it made quite an impression on me: “You should know that I belong to the hawks here; the second we come under attack, I will be just as hardline as the others.”

schmidt: Let’s depart the subject of Israel, Fritz. Nothing positive comes of it.

stern: Then we would be one-sided, because in our discussions up to this point only Israel has made mistakes. The role of the Palestinians deserves some mention. We cannot forget what happened in Munich in 1972, and the whole terrorist movement on one hand, and on the other the fact that the misery of the Palestinian people was in the end also the fault of the rich Arab states, who could not have cared less about them–

schmidt: Historically, the beginning of this entire dramatic problem lies with the Balfour Declaration in 1917. The English promised the Jews their own territory, without imagining that one day the state of Israel would develop out of it. They were focused on a series of Arab administrative districts which were formally a part of the Ottoman Empire and were ruled from Constantinople. It was an extremely complex situation. There was no state called Saudi Arabia, no state called Syria, no state called Iraq. There was only the state of Lebanon. All the other areas were under Turkish administration.

stern: The Balfour Declaration of 1917 did not speak of an Israeli state but rather of a Jewish Homeland, and the British did not promise it to the Zionists just out of generosity but rather because of their assumption that in this way they could develop Palestine as a long-term base for themselves. That’s the way many of the Zionists attempted to sell it to the English: We will be your Gibraltar in the east, you will have two important anchors in the Mediterranean, one at Gibraltar and the other, a Jewish Palestine.

schmidt: I believe that one of those who could have developed a clear vision of the future of the state of Israel, had they wanted to speak of it, would have been Nahum Goldmann.

stern: A very interesting man. He left me one of his briefcases. He was also deeply engaged for the state of Israel. — But I wanted to say: the indifference of the Arab states towards the Palestinians is puzzling.

schmidt: You shouldn’t forget that these so-called Arab states had at first no legitimacy. They were all the artificial creations of the Allies in the course of the treaties concluded in the suburbs of Paris in 1919. None of them existed before that point.

stern: But I mean the conduct of the surrounding Arab states today. Or in 1948, at the time of the founding of the state of Israel, when they obviously all existed.

schmidt: They existed at that time, but they were very fragile states, without exception dictatorships, and the governing families sat on an unstable throne and had to hustle as a domestic matter to hold on to power. That is true for Jordan; that is true for Syria. Having Israel as an enemy was a help to them.

stern: Just the same it is a ray of hope that Israel is a democracy, even if a gruff one, but a democracy just the same. We can’t say that of the Arab states in the region. They are all more or less feudal states or dictatorships.

schmidt: From the perspective of international law, it makes no difference whether they are democracies or dictatorships.

stern: But taking into account what we discussed yesterday and today, we can say that Israel has one advantage over the dictatorship of its neighbors: it is a democracy. One of the points of hope relating to the future of Israel is the Supreme Court, which maintains itself in the best sense of the words conservative and liberal–it keeps a check on its own government in questions of intolerance and torture. The Supreme Court is an important and a positive authority.

schmidt: When I consider that the Supreme Court does not even recognize marriages between Jews and non-Jews, I am more skeptical than you. But let’s put this subject aside…