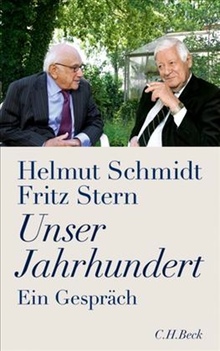

With the kind permission of C.H. Beck Verlag, former German chancellor Helmut Schmidt, and Columbia University historian Fritz Stern, we present here the third in a series of excerpts from the bestselling book Unser Jahrhundert – Ein Gespräch, in an original English translation.

iii. parties, fiscal and democratic accountability

stern: The question is how long the population in a democratic system will play along [with policies of fiscal irresponsibility]. It’s not a question of the individual member of parliament who drops out at some point. I understood you from the start to mean that “dropping out” amounts to a rejection of society, of the entire system.

schmidt: That’s not what I meant. I mean specifically the situation in which a parliamentary deputy defies party discipline, declines to vote as his leadership asks, and perhaps even leaves his party. One of the great weaknesses and dangers of democracy is that a party that wants to govern has to sell itself to the people, even with respect to fiscal policy –

stern: Especially with respect to fiscal policy. The opposition of many Americans to taxation is enormous; they hardly seem to recognize the extent to which they rely on state services, even in their day-to-day life.

schmidt: Politicians attach themselves to all sorts of rescue maneuvers, whether Opel or Quelle or Abwrackprämie, in the expectation that this will win them some votes. The bill is delivered later. What helps politicians at present is the circumstance that in concept all major states are reacting to the crisis in the same manner, whether they are democracies or authoritarian states like Russia or communist states like China. If all of these governments had not announced an economic rescue program of legendary measure (and thereby assumed an enormous state debt), then today we would be faced with five million unemployed in Germany, five million unemployed in France and fifty million unemployed in China. All states of the world did the same, namely that implemented enormous economic rescue plans and pressed their central banks to assist by making the necessary money available. All did the same. And that is in my view very fortunate, because from 1929 to 1932 almost every state behaved differently, and in each case falsely.

stern: Exactly! Then there was an enormous economic illiteracy. Most believed that they had the right measure to cure a depression, namely deflation, spending less money. The thought that one should spend more money to help the economy lift itself out, to suppress unemployment, occurred to very few. But – and this would be my question to you – at some point the deficit spending has to come to an end. Indeed, the Germans have just put a limit on deficits in the Grundgesetz.

schmidt: You shouldn’t take that too seriously. There has never been a state that operated without deficits. I exclude the oil exporting countries, the United Arab Emirates or Saudi Arabia. That doesn’t mean that the state can’t run up debts as it likes. Every excessive indebtedness of a state – it must be serviced on one hand, and at some point extinguished on the other – leads to an accumulation of cash that expands the purchasing power, particularly when the central bank plays along, which they presently do. The final effect of excessive indebtedness is an inflationary movement of prices. That is unavoidable. That occurred in both world wars, in all affected states, and it will follow just as certainly following the current crisis, after it has been surmounted – the question is only when that will be. The consequence is an inflationary development. That is not to be avoided.

stern: The development in America was somewhat different. Government debt rose horribly in the eight years under George W. Bush –

schmidt: That began with Reagan. In that connection, one has to express respect for the eight years of Clinton, he brought the American budget back into order.

stern: That’s just what I wanted to say: George W. Bush inherited a balanced budget from Clinton, and he left behind a massive deficit. And then his boasts to be a conservative!

schmidt: The decisive weakness of the American state, which was first apparent during the Reagan era, is the balance of trade deficit. As long as the state’s debts are with its own citizens, that’s its own thing; but when the American State has $2 trillion in debt to the Chinese and $1 trillion to the Japanese, and another $1 trillion to the French, Germans, Swiss, Russians and the OPEC countries, then serious problems arise.

stern: Debt inside one’s own family, if I can call it that, is a burden for future generations. However, if one runs up enormous debts with outsiders, then one is subject to their extortion. For a great power like America that is –

schmidt: More theoretical than practical at present.

stern: At present.

schmidt: Yes, for instance the Chinese, with $2 trillion in their currency reserves at present, are hardly about to sell them to someone else to come up with cash payable in Euros or Yen.

stern: As long as the return is correct and as long as the investment is relatively secure, the Chinese are not likely thinking of a sale. And the return is still higher in America than in the rest of the world. But if interest rates climb, that would quickly become a burden for the Americans.

schmidt: Yes, indeed.

stern: An important predicate for restoring order would be that America restores a better balance between imports and exports. At present American consumers purchase every imaginable product from abroad without being in the position of selling their own goods abroad. But up to this point Americans have had little need to produce goods for export because of their enormous domestic market.

schmidt: In any event they didn’t feel they were under any special pressure to do so. There are two exceptions: the American armaments industry and the American aviation industry.

stern: But the problem in America isn’t just the foreign indebtedness. One shouldn’t forget–and it will certainly extend the financial crisis–that Americans also have enormous private debt–that they live off their debt. It’s hardly coincidental that the global financial crisis began with the American real estate market. And we’re far from the end of this crisis. I think and hope that Obama is on the right path. In any event he had the courage to tell the American people about the seriousness of the situation during the election campaign. Very few politicians are willing to take such a risk because they know that generally this is not the way one wins the next election.

schmidt: You’re right–a responsible politician can only proceed to tell the people how serious the situation is with the most careful contemplation, whether in Germany or in America. But that is not only related to the election campaign. Put yourself in the position of a doctor, and you have before yourself a patient, about whom you know that he has cancer, prostate cancer. The spread of the cancer to the rest of the body can take a very long time. You must tell him: You have cancer. But do you want to tell him: In your case, I reckon that you have two more years. As a doctor, you wouldn’t do that. The politician’s situation is similar. To tell the patient how serious his situation is without being able to change the situation would be only to reduce the patient’s confidence.