Toute race, tout art a son hypocrisie. Le monde se nourrit d’un peu de vérité et de beaucoup de mensonge. L’esprit humain est débile; il s’accommode mal de la vérité pure; il faut que sa religion, sa morale, sa politique, ses poètes, ses artistes, la lui présentent enveloppée de mensonges. Ces mensonges s’accommodent à l’esprit de chaque race; ils varient de l’une à l’autre: ce sont eux qui rendent si difficile aux peuples de se comprendre, et qui leur rendent si facile de se mépriser mutuellement. La vérité est la même chez tous; mais chaque peuple a son mensonge, qu’il nomme son idéalisme; tout être l’y respire, de sa naissance à sa mort; c’est devenu pour lui une condition de vie; il n’y a que quelques génies qui peuvent s’en dégager, à la suite de crises héroïques, où ils se trouvent seuls, dans le libre univers de leur pensée.

Every nation, every art has its hypocrisy. The world is fed with a little truth and a great many lies. The human mind is feeble: only rarely can it accommodate unalloyed truth; its religion, its morality, its politics, its poets, its artists, must all be presented to it enveloped in falsehoods. These lies are adapted as suits the mentality of each nation: they vary from one to the other. But these very falsehoods make it so difficult for nations to understand one another, and so easy for them to develop hatred towards one another. Truth is the same for all of us: but every nation has its own lie, and to this it applies the word idealism. Every creature therein breathes it from birth to death. It becomes a fact of life–there are only a few men of genius who can break free from it through heroic moments of crisis, when they are alone in the free world of their thoughts.

—Romain Rolland, Jean-Christophe, vol. 4: La Révolte (1905)(S.H. transl.)

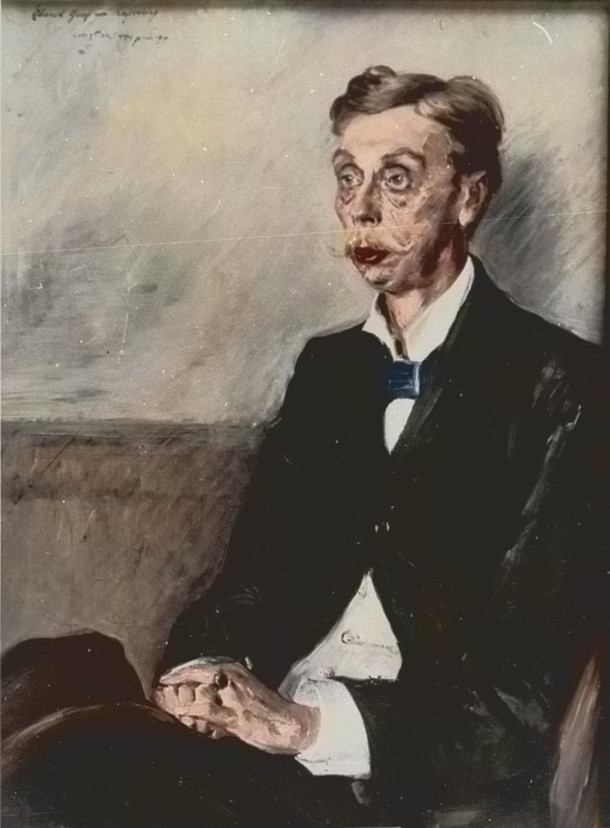

The lazy days of summer, a friend recently told me, are the time for us to actually read those books we’ve always claimed to have read, but haven’t. Romain Rolland’s river of a novel, Jean-Christophe, has been on my reading list and my bookshelves since college, but the massive volumes always intimidated. Writers I greatly admire–Leo Tolstoy, Thomas Mann, Hermann Hesse and Stefan Zweig, for instance–were deep admirers and friends of Romain Rolland. In the early years of the twentieth century, he was a commanding presence in the literary world. Today, however, who reads him? Rolland’s work does not seem to have aged well.

But reading it, I did not find this work to be dated or irrelevant. Neither did I find the mature work of distant sagacity that I expected. Rolland’s novel is filled with a curious passion. It looks at one level like a typical German Bildungsroman, but it attacks so many themes and ideas. Rolland gives us a musical genius, a thinly veiled portrait of Beethoven, transposed into the end of the nineteenth century and catapulted out of Germany and into France. He addresses idealism and the challenge of genius, the crisis of composition, the unquenchable impulse to create. But the book also has an unmistakably political moment. Rolland takes dead aim at the jingoistic nationalism of the late nineteenth century and warns of the mass slaughter that it surely will (and indeed did) produce, and he does this in a work completed on the eve of the Great War. Every nation, he tells us, has its own greatness of spirit and its unique gifts, but every nation deludes itself by imagining these gifts to be something other than what they really are. Pride, religious bigotry, racism, a sense of cultural superiority–these attitudes are the clear markers of a destructive immaturity in Europe that will produce great ruin if not purged. And in successive chapters he offers flattering praise and then devastating criticism of the three nations which for him form the heart of Europe–France, Germany and Italy. Not the national interest, but justice, he argues, must become the lodestar for Europe’s nations. “I love my homeland,” he says at one point to a foreign friend, “I love it every bit as much as you love yours. But can I for the sake of that love murder innocent souls or betray my conscience? That would be a betrayal of my homeland. I number among the army of the spirit, not the army of violence.”

The nationalism of his era is, Rolland writes, infected with lies and enshrouded with prejudices. It is not a nationalism worthy of the people in whose name it is hoisted as idealism. A truer national pride values the accomplishments of one people without needing to resort to fear and hatred of others to make its point. It projects confidence and loves justice. It exults peace and forbears violence. It is willing to accept that political actors invoking the name of the nation may do wrong and merit punishment for it–and it refuses to connect their interests with those of the nation. It values critical introspection that aims towards improvement and avoids making virtues of its own failings.

Rolland’s strident pacifism is hardly a practical approach to global politics. His trip to the Soviet Union and the accolades he once bestowed on Stalin reflect an embarrassing weakness in appraising political leaders. But when it came to Europe’s core, Rolland stood on firmer ground and offered a powerful vision of a new Europe. And it seems that Rolland’s vision has affected the Europe that emerged from World War II every bit as much as that of Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman. Jean-Christophe Krafft, his protagonist, may indeed be a reincarnation of Beethoven, but he is also the spirit of a Europe that might be, and now, a century later, draws ever closer to reality.

In a letter published by The Nation in 1931, Romain Rolland describes his meeting with Mahatma Gandhi:

On the last evening, after the prayers, Gandhi asked me to play him a little of Beethoven. (He does not know Beethoven, but he knows that Beethoven has been the intermediary between Mira [Slade] and me, and consequently between Mira and himself, and that, in the final count, it is to Beethoven that the gratitude of us all must go.) I played him the Andante of the Fifth Symphony.

Listen to a performance of the andante movement from Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in C Minor, op. 67 (1808), in the transcription of Franz Liszt, which Rolland used. Idil Biret performs: