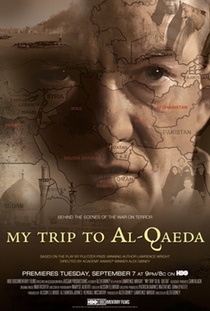

Author Lawrence Wright has gained acclaim for his penetrating studies of Arab terrorists, from the Muslim Brotherhood to Al Qaeda. His work, regularly featured in The New Yorker, has included The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11, which received the Pulitzer Prize in 2007, and the screenplay for The Siege, a 1998 film that forecast America’s reaction to a terrorist attack with uncanny precision. Wright’s one-man play about his personal experiences in writing The Looming Tower and related works, entitled My Trip to Al Qaeda, will premier on HBO on Tuesday, September 7 at 9 p.m. in a film directed by Alex Gibney. I put six questions to Wright about his new film.

1. My Trip to Al Qaeda chronicles your journeys deep into the Arab world, to Cairo and Jeddah. Would it be fair also to describe it as an internal voyage—Larry Wright struggles with his need to be analytically objective on one hand, and yet also deal with his rage over the stubborn stupidity of Al Qaeda leaders, their acts of barbarity against innocents, their perversion of religion, as well as a measure of rage against American political leaders who betrayed the nation’s values in the name of a struggle against terrorism?

While I was researching The Looming Tower I never intended to play a role other than that of the objective reporter. But, like all Americans, I was grieving and angry because of the attacks. Sometimes those feelings erupted with a heedless intensity that caught me by surprise. There were some awful moments; in particular, I recall a furious argument with one of the leaders of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood after I had heard one too many lectures from Islamist propagandists. Even more disturbing, I suppose, were times when I felt a sense of fellowship with people I knew had blood on their hands. For me, it was a journey into a land of moral complexity, one that often left me grasping for certainties that weren’t readily at hand.

2. What drove you to develop this as a one-man play, rather than a more conventional format, like a polemical essay?

In 1991, I saw Anna Deveare Smith perform her one-woman show, “Fires in the Mirror,” about the Crown Heights riot, and I was riveted. I’ve always loved theater, but I never imagined it could be married to journalism. Then, a few years later, David Hare, the British playwright, asked to use a line I had written in The New Yorker for his one-man show about Jerusalem, “Via Dolorosa” (he wound up deciding not to use it). Both of those precedents were in my mind when I decided to do this play.

Actually, for a reporter, this feels very natural. I think our job is to act as a witness for our community. We go out and learn what’s going on, then we come back and make a report. It must have been like that when humans were sitting around campfires. Someone goes over the hill to see what’s there, then he returns to tell the others. When I’m standing on the stage, seeing the lights reflected on the faces of the audience, I feel that kind of intimate contact.

3. You start the HBO version with President Obama’s speech in Cairo. Of course, just last week polling showed that the initial surge of enthusiasm for Obama in the Arab world has subsided, and skepticism is now setting in. Has Obama delivered on the promise of that speech? If not, what did he fail to do in the first eighteen months of his presidency?

The Arabs are taking Obama’s measure by what he accomplishes in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which is, really, nothing so far. Obviously, this is an intractable conflict that has defeated many stout attempts by past administrations, but it’s not insoluble, and anyone who cares about this ongoing tragedy has a right to be frustrated at the absence of powerful initiatives and fresh ideas.

4. You talk about Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, Osama bin Laden’s brother in law, who was murdered in January 2007. What do you think of Khalifa, his relationship to Al Qaeda, and the circumstances of his death?

Jamal is a complicated figure for me. I really liked him. It was difficult to maintain objectivity around him; he was too spontaneous and full of fun. The fact that he was bin Laden’s best friend made me see a side of the terrorist leader that was all too human. Jamal had distanced himself from bin Laden and had publicly condemned him in the Arab press. Moreover, he had asked me for help in clearing his name. He wanted me to contact the FBI to set up an interview for him. I did so, but the Bureau refused to meet him in Saudi Arabia. Jamal told me that he had cleared the meeting with the Saudi Interior Ministry, so I don’t think that was the obstacle. I was later told by a source in the Bureau that the CIA had nixed the idea.

Because of his closeness to bin Laden, and his kinship, Jamal knew many people in Al Qaeda. I don’t think he was ever a part of it. He was always really candid with me. He even interviewed his wife on my behalf. As a very conservative Saudi woman, bin Laden’s sister would never talk to me, but Jamal stayed with her every fourth night (he had three other wives), and he would bring my questions with him. That was incredibly helpful. Because he was such a terrific source, and such a likeable personality, it’s possible that there were aspects to his relationship with bin Laden that I overlooked. But I don’t think so.

I’ve gone through the FBI and Justice Department documents on Jamal that I obtained through FOIA requests, and there’s absolutely nothing in there that implicates him. And yet, many analysts in the intelligence community assumed that, because he was bin Laden’s brother-in-law, he must have been entangled in Al Qaeda. Once I heard a well-known writer, who teaches counter-terrorism to international police agencies, declare that Jamal was on the Al Qaeda shoura council. That was wrong and ridiculous, but it may have gotten Jamal killed. I think he was assassinated by American Special Forces on the mistaken assumption that he was an Al Qaeda operative. I can’t prove it. He was murdered in Madagascar. No one was arrested in the killing.

5. At several points you analyze the rhetoric of Al Qaeda and you point to their strange juxtaposition of two concepts: “humility” and “humiliation.” How are these concepts employed and what do you learn from the contrast?

Humility is a highly valued character trait in Islamic culture. When bin Laden’s followers praise him, they often invoke this quality. The fact that bin Laden is from a wealthy family makes this aspect of his personality all the more appealing.

Humiliation, on the other hand, is imposed from the outside. It is one of the most common words in bin Laden’s vocabulary. For many Muslims who resonate with the term, their humiliation may be cultural or religious in nature – the sense of Islamic societies being overpowered by Western values, mores, and political dictates.

But it is also true that a number of Muslims have been physically humiliated. Ayman al-Zawahiri, for instance, the number-two man in Al Qaeda, the doctor always at bin Laden’s elbow, was imprisoned for three years in Egypt following the Sadat assassination. Like many of his companions, he was brutally tortured. I think the particular appetite for carnage that sets Al Qaeda apart from other terrorist organizations was born in the humiliation such men suffered in those prisons.

6. One of the most jarring points in your narrative is an encounter with FBI agents who demand to know why you’ve been calling a number in Britain and ask about your daughter. Tell us what happened and what significance you attach to the incident.

In the movie, I talk about two members of the Joint Terrorism Task Force who came to my office to ask about phone calls that I made to a number in London. It belonged to a solicitor who represented some of the jihadis I had been interviewing. During the course of the conversation, they asked who “Caroline Wright” was. That’s my daughter. She was a university student at the time, not living at home. None of our phones were registered in her name. The only way I could imagine that they got her name was by listening to my phone calls.

There’s another instance that I didn’t mention in the movie. Before this episode, I had been told by a source at the Counter-Terrorism Center that my source had seen a summary of a telephone interview I had with Zawahiri’s cousin in Cairo. At the time, I figured that the Egyptians had covered the conversation and supplied it to the CIA. On December 16, 2005, when the New York Times revealed that the NSA was illegally wiretapping Americans, I thought otherwise.

I’m glad the JTTF came to my house to clear this matter up, but it’s an example of the danger of awarding government such extraordinary powers. A simple misunderstanding such as this could easily have led to having Caroline’s name placed on an FBI link chart, only two steps away from Al Qaeda.

One day, Al Qaeda will fade away, but we will still be left with the swollen security state that we’ve created to fight it. That’s another challenge we haven’t begun to face.