“You, most blessed and happiest among humans, may well consider those blessed and happiest who have departed this life before you, and thus you may consider it unlawful, indeed blasphemous, to speak anything ill or false of them, since they now have been transformed into a better and more refined nature. This thought is indeed so old that the one who first uttered it is no longer known; it has been passed down to us from eternity, and hence doubtless it is true. Moreover, you know what is so often said and passes for a trite expression. What is that, he asked? He answered: It is best not to be born at all; and next to that, it is better to die than to live; and this is confirmed even by divine testimony. Pertinently to this they say that Midas, after hunting, asked his captive Silenus somewhat urgently, what was the most desirable thing among humankind. At first he could offer no response, and was obstinately silent. At length, when Midas would not stop plaguing him, he erupted with these words, though very unwillingly: ‘you, seed of an evil genius and precarious offspring of hard fortune, whose life is but for a day, why do you compel me to tell you those things of which it is better you should remain ignorant? For he lives with the least worry who knows not his misfortune; but for humans, the best for them is not to be born at all, not to partake of nature’s excellence; not to be is best, for both sexes. This should our choice, if choice we have; and the next to this is, when we are born, to die as soon as we can.’ It is plain therefore, that he declared the condition of the dead to be better than that of the living.”

—Aristotle, Eudemus (354 BCE), surviving fragment quoted in Plutarch, Moralia, Consolatio ad Apollonium, sec. xxvii (1st cen. CE)(S.H. transl.)

Examine the original Greek text in the Dübner edition used by Friedrich Nietzsche, with the quoted passage on pp. 137-38.

“Stat rosa pristina nomine, nomina nuda tenemus” reads the last sentence of Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose. “Yesterday’s rose continues in its name, but the names we keep are hollow.” The motto fits Eco’s work on many levels—he introduces his reader to the rediscovery of classical antiquity in the depths of the Middle Ages, to the battle between religious doctrine and science, to the brave reassertion of humanism. And one of his points is how the greatness of thought of the past eludes us even as the words remain. In the background of Eco’s novel is the discovery of Aristotelian texts, long vanished, in the library of a Benedictine monastery in remote northern Italy—the struggle to save these texts leads to a series of murders, and at last the texts are lost as a fire consumes the library. One of the most famous of the lost writings of Aristotle is Eudemus or On the Soul, a relatively youthful work on a point that may have been difficult to reconcile with the dogma of the medieval church fathers (a fact which may help explain why it did not survive). Only a few scraps of this work have been handed down, the most important being this quotation by Plutarch in a later work of philosophic consolation. In it we learn the essence of what later philosophers have come to call “the wisdom of Silenus.”

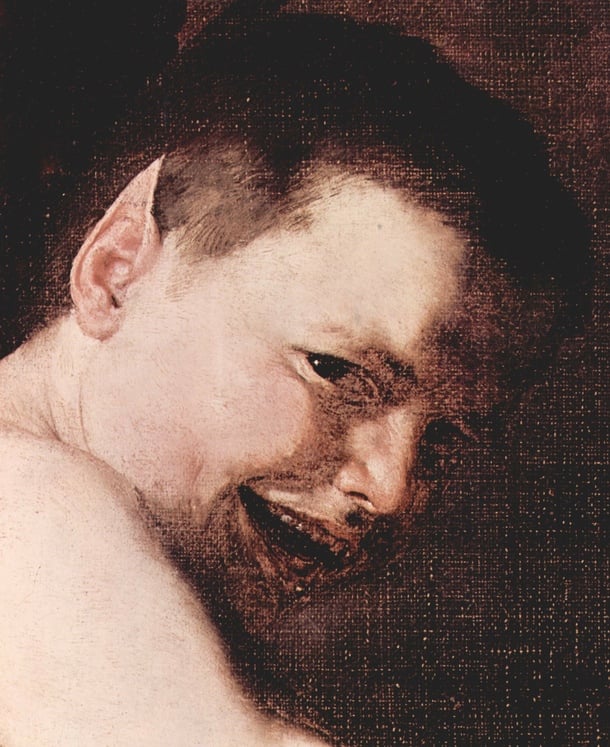

It’s a perfect example of what Eco means by “empty names.” In popularized lessons from antiquity, we have Bacchus and the satyrs, foremost Silenus, the most drunken and the wisest among them, who come down to us as images associated with drunken debauchery. But in antiquity, Silenus is a figure of serious thought involving a good bit of melancholy. He is an immortal, but he plainly sees this as a punishment–he is trapped in unending life. Silenus envies the humans for their fixed, relatively fleeting existences on earth. He turns to alcohol and other tools of intoxication, stimulation, and arousal–all of this a flight from reason, an escape from consciousness of his existence. He celebrates the immediate pleasures of life. But he is also described as shy and withdrawn, uncertain of himself. Silenus comes to play an important role in the thinking of Aristotle and Plutarch, he presents us with the dilemma of mortality and the horror of life without death. Then for centuries he is relegated to the role of garden ornament, with rare exceptions, like Jusepe de Ribera’s fascinating painting of a youth who may be enraptured or may be tormented. Finally in the mid-nineteenth century classicists aided by archaeological discoveries began to probe once more into the inner truth, the psychological dimension of these characters and images. They began to probe the Dionysian cult and what it represented to those who practiced it.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s writing on the Dionysian state marks a decisive turning point in the scholarship. It marks the rediscovery of the wisdom of Silenus. Nietzsche’s Silenus has immediate relevance to the ultra-nationalistic, militaristic Europe that surrounded and disgusted him. As Julian Young describes Nietzsche’s modern Dionysius cult, it meant a “dwindling of the political instinct,” an “indifference, even hostility towards the state.” “In the consciousness that comes with the awakening from intoxication, he sees everywhere the horror or absurdity of human existence; it nauseates him. Now he understands the wisdom of the forest god.” That god’s name, is, of course, Silenus.

Rudolf Nureyev performs to Claude Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un Faune (1894):