The last and greatest cause of this malady [melancholy], is our own conscience, sense of our sins, and God’s anger justly deserved, a guilty conscience for some foul offence formerly committed… A good conscience is a continual feast, but a galled conscience is as great a torment as can possibly happen, a still baking oven, (so Pierius in his Hieroglyph, compares it) another hell. Our conscience, which is a great ledger book, wherein are written all our offences, a register to lay them up, (which those Egyptians in their hieroglyphics expressed by a mill, as well for the continuance, as for the torture of it) grinds our souls with the remembrance of some precedent sins, makes us reflect upon, accuse and condemn our own selves… A continual tester to give in evidence, to empanel a jury to examine us, to cry guilty, a persecutor with hue and cry to follow, an apparitor to summon us, a bailiff to carry us, a serjeant to arrest, an attorney to plead against us, a gaoler to torment, a judge to condemn, still accusing, denouncing, torturing and molesting…Well he may escape temporal punishment, bribe a corrupt judge, and avoid the censure of law, and flourish for a time.

—Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it is: With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Maine Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up, pt iii, sec iv, mem 2, subsec iii (1621).

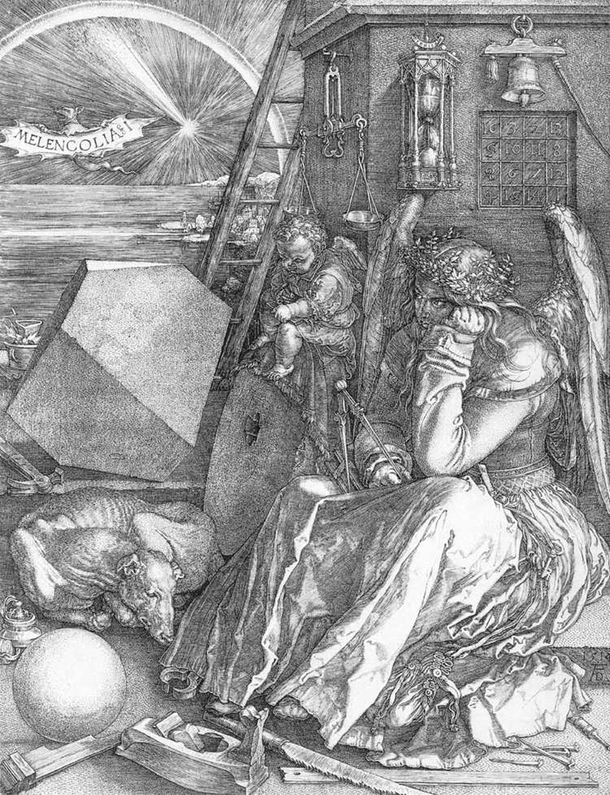

Burton’s Melancholy may be the ultimate statement of the late medieval and Renaissance theory of humors, which suggested that human moods resulted from the presence of certain fluids in the body. Melancholy itself, what we today would call depression, was understood to result from an excess of black bile, for instance. Burton’s book has limited continuing value as a work of science (it is interesting, perhaps, as a threshold discussion of cognitive science), but as a work of literature and literary criticism it’s eccentric and fascinating. It runs to several volumes and can’t be read smoothly. Best to break it into nuggets and consider them–like the discussion of conscience and its relationship to melancholy, reproduced above, which is filled with a long repertory of literary and philosophical comparisons. (The relationship to Shakespeare, and particularly works like Macbeth and Richard III, is very strong).

Burton is driven by a study of the mind and he is convinced that human society can only advance by mastering the workings of the mind. He sees depression as a serious obstacle, a condition which regularly afflicts the scientifically and artistically gifted. He is committed to understanding what causes it and how it can be combatted. In all of this, he offers some brilliant insights mixed with hopelessly outdated science. It’s easy to see him as both as a literary critic and as the progenitor of behavioralist thinkers like B.F. Skinner.

The flavor of melancholy is contained in much of the music of the Elizabethan and Jacobean era, for instance, in the compositions of Burton’s contemporary, the lutenist and songwriter John Dowland. But let’s try a more symphonic approach to the theme. Listen to the third movement of Carl Nielsen’s Symphony No. 2 (1902), entitled “Melancholy,” and inspired by Burton’s book. Here is a splendidly depressing performance of the work by the Helsinki Symphony: