In Berlin, on November 9th, people placed votive candles before a neighborhood synagogue. A sign in front of a busy train station reminded passersby that trains once took passengers to Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Flossenbürg, and a host of other detention camps. And crowds thronged to an exhibition at the German Historical Museum: “Hitler and the Germans.” It was the anniversary of Kristallnacht, the massive pogrom perpetrated, in 1938, against Jewish homes, businesses and institutions in Berlin and nationwide.

In the Germany of the seventies and eighties, the Nazi past was still the “unbewältigte Vergangenheit”—the “unreconciled past.” It was simply too horrible to think about, went the embarrassed explanation. Besides, grandma and grandpa would be upset; they would often explain that they “knew nothing about all that.”

But the organizers of “Hitler and the Germans” seem to have had grandma and grandpa in mind. Their powerful exhibition shows the rise of Adolf Hitler in the context of German popular culture. It illustrates the horrors of the rise of the Nazi party, accompanied by casual, widespread and largely unaccountable acts of violence against favored targets of persecution—Jews, socialists, and gays prominent among them. “Hell is in charge now,” wrote Joseph Roth to Stefan Zweig in one poignant account of the transfer of power to the Nazis in 1933. The exhibition patiently chronicles the evolution of racial policies: the Nuremberg laws, internment camps, and the “final solution.” It maps the Nazis’ expansionist plans, their goal of creating a new Thousand-Year Empire with the incorporation of lands of the Slavic east, coupled with the deportation of indigenous peoples and their resettlement. These facts constitute the historical bone structure of the Nazi period, but the exhibition’s highest achievement is that it develops all this history through the use of German popular culture of the period—films, newspapers, pamphlets, posters, artifacts of daily life. In other words, things of which grandpa and grandma could not credibly claim ignorance. The exhibition demonstrates not only how pervasive pro-Nazi pop culture was, but how personally popular Hitler was among the Germans, and how the Hitler cult grew dramatically after he came to power.

In the bookshop at the end of the exbition sat a small mound of copies of Hitler’s Willing Executioners, the Daniel Goldhagen work that generated a storm of controversy upon its publication in 1996. There is certainly plenty of room to quibble with some of Goldhagen’s specific findings, but no one emerging from “Hitler and the Germans” is likely to question its thesis: that ordinary Germans knew of and approved of Hitler’s genocidal policies.

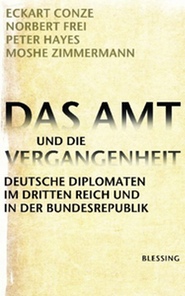

Unpleasant but essential recollections—this was the theme of another event only a short distance away, at Berlin’s House of World Cultures. The subject was the history of the German Foreign Office (known to initiates as “das Amt”), and, in particular, the dark secrets of its engagement during the Nazi period and the role played by its Nazi alumni in the decades that followed. The exhibition is drawn from the work of a panel of prominent historians, a 900-page tome called Das Amt und die Vergangenheit (The Foreign Office and the Past). The book had a curious genesis. In May 2003, Marga Henseler, a 92-year-old former staffer at the Foreign Office who served at the German embassy in Washington and the consulate in Los Angeles, wrote Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer to express her anger over the fact that an obituary had run honoring a recently deceased diplomat. This man, Henseler explained, was a terrible Nazi with blood on his hands, and it was absurd to honor him in a Foreign Office publication. The letter drew no initial response, and Henseler redirected it to Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, who then showed it to Fischer and suggested that it merited his attention. Fischer then acted, instructing the in-house bulletin of the Foreign Office to desist from “honoring with an obituary former staffers who were members of the Nazi party.”

Fischer’s act drew an almost immediate counterattack from conservative alumni of the Foreign Office, who said Fischer was motivated by his own radical left-wing past (Fischer, a Green, acknowledges having participated in sometimes violent student demonstrations in the late sixties and early seventies). Fischer’s response: appointing a commission of eminent historians, and giving them full access to the Foreign Office’s records and archives and a mandate to produce a history of German diplomats in the Third Reich and their legacy in the era of the Federal Republic.

For decades, the Foreign Office has strained to portray itself as a bastion of professionalism that stood above the fray and craziness of the Nazi era. But Das Amt tells a different story, and it tells the story authoritatively. The Foreign Office was committed to and engaged in the fulfillment of every aspect of Nazi policy with foreign policy implications, including forced labor, deportations, and the establishment of concentration and extermination camps. Consider, for instance, the mid-level official Franz Rademacher, who, in 1943, submitted a travel reimbursement form and noted this reason for his trip: “the liquidation of Jews in Belgrade.” This sort of document was not classified; it was visible to everyone—down to the functionaries in the ministry’s bookkeeping department. After World War II, the Foreign Office had a substantial number of officials who were former Nazis, many of whom had played horrific roles during the Nazi era. Yet there was no systematic effort to identify them, learn of their crimes and judge their suitability for further service. In fact, the Foreign Office opened a department to render them free legal advice. Diplomats and staffers were warned against traveling to certain countries lest they become involved in criminal investigations; legal services were offered to those who got drawn into such investigations. In this way the Foreign Office actually obstructed pending criminal investigations into the activities of its staffers.

The publication of Das Amt is vindication for Fischer in the debate over his simple ministerial directive about obituaries. “Now they have received the obituary that they have earned,” he says, a conclusion that few will openly dispute.

But Das Amt and “Hitler and the Germans” also mark the end of the “unreconciled past” in Germany. Today the solemn remembrance of gross injustices of the past is for many an act of civic responsibility.