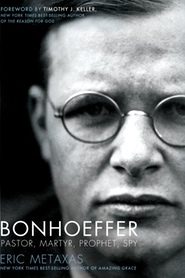

Eric Metaxas, whose best-selling biography of William Wilberforce, Amazing Grace, provided the framework for an important motion picture, is now out with a thick review of the life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German pastor and theologian who played a key role in one of the attempts to kill Adolf Hitler. I put six questions to Metaxas about Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy:

1. You dedicate your book, in German no less, to your grandfather. Tell us the significance of that dedication, and how in the course of your own life you were drawn to Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

My grandfather was a genuinely reluctant German soldier who was killed in the war in 1944, at the age of 31. My mother was nine. The tragedy of my mother’s losing her father at that age has been a big part of my life. My grandfather didn’t want to fight in Hitler’s war. My grandmother said that he used to listen to the BBC with his ear literally pressed against the radio speaker, because if you were caught listening to the BBC you could be sent to a concentration camp. The boss in the factory where he worked was a friend of the family–I met him in 1971–and he was able to keep my grandfather from being drafted until 1943. Of course that wasn’t quite long enough.

When I first heard the story of Bonhoeffer in 1988, I was staggered. I was slowly returning to the Christian faith that I had lost as a student at Yale, and Bonhoeffer’s personal story and his magnificent book, The Cost of Discipleship, really spoke to me and helped me as I struggled with my questions. As a German-American, I was especially touched by his story, because he was a German who had spoken up for those who couldn’t speak. First and foremost for the Jews of Europe, but also for many like my grandfather, who were powerless and who in their own way were also victims of the Nazis.

The dedication to my grandfather, for whom I’m named, includes a quote from the Gospel of John, where Jesus says that those who believe in Him will be “raised up on the last day.” Because of that promise I hope that I will actually get to meet my grandfather.

2. Albert Einstein was famous for saying that a “foolish faith in authority” was a core weakness in German society. German writers like Heinrich Mann, Hermann Hesse, and Frank Wedekind depict an educational system designed to break the individual’s will and make social conformists. But Dietrich Bonhoeffer emerged from this milieu unbent and with a strong contrarian streak. What is it about Bonhoeffer’s personality and upbringing that built such a determined opponent of the Nazi state?

Somehow Bonhoeffer’s time in New York, especially his worship in the “negro churches,” played their part… He had heard the gospel preached there and had seen real piety among a suffering people. The fiery sermons and the joyous worship and singing had all opened his eyes to something and had changed him. Had he been “born again”?

What happened is unclear, but the results were obvious. For one thing, he now became a regular churchgoer for the first time in his life and took Communion as often as possible… Two years earlier, in New York, he hadn’t been interested in going to church. He loved working with the children in Harlem, and he loved going to concerts and movies and museums, and he loved traveling, and he loved the philosophical and academic give-and-take of theological ideas–but here was something new.

—From Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy

Reprinted by permission of Thomas Nelson – © 2010 Eric Metaxas

The Bonhoeffer family were not mere contrarians or “anti-authority” in the shallow contemporary sense, but they did seem to have a rare and healthy perspective on themselves and on Germany. They were patriotic, but they were wary of certain impulses in the German national character. Bonhoeffer’s mother was a serious Christian who homeschooled her children because she didn’t like the authoritarian character of German public schooling at that time. She would quote the saying that German children “had their backs broken twice,” first in school and then in the military.

Of course a serious Christian perspective makes one wary of knee-jerk anti-authoritarianism, too. Anti-authoritarianism is the typical and opposite American impulse. That’s part of our national character and what we need to guard against. Bonhoeffer saw it at Union Theological Seminary in New York and was quite put off by it. The real question for Bonhoeffer was “What is legitimate authority?” In America we have by now swung so far in the anti-authoritarian direction that we have bumper stickers that say “Question Authority.” This implies that all authority is suspect, but Bonhoeffer would disagree. We are to question authority to determine whether it is legitimate. But to imply that all authority is illegitimate and mustn’t be obeyed is no different than saying that all authority is legitimate and must be obeyed.

As I say in the book, Bonhoeffer gave a famous speech two days after Hitler became Chancellor in which he deals with this issue explicitly. It is just as important today for us as it was then in Germany, but perhaps in the opposite direction.

3. John Baillie and Reinhold Niebuhr wrote that Bonhoeffer, during his time in New York, was tenaciously non-political. You give us a Bonhoeffer who seems to have taken sides in the controversy that then raged between “modernists” and “fundamentalists,” siding with the latter, who admired in particular the fundamentalist churches of Harlem, and who was appalled and moved by the sufferings of American blacks. Is there any contradiction between these two portraits?

Not at all. As Whitman says in Leaves of Grass, “I am large. I contain multitudes.” The truth is inevitably large and forces a wider perspective on things. Bonhoeffer was not a liberal or a conservative, but a Christian. He was zealous for God’s perspective on things, and God’s perspective is inevitably wider than the standard parochial political points of view. It sometimes forces us toward a liberal view and sometimes toward a conservative view.

But because Bonhoeffer has been so consistently portrayed as a theological liberal–which he was not–it’s important for us to see the other side, and I hope I’ve shown that in my book. He is clearly horrified at the way so many at Union Theological Seminary had cavalierly dispensed with the fundamentals of the Christian faith and had created an ersatz religion in their own progressive image. He was impressed with and moved by their earnest desire to help the poor, for example, but he wondered on what basis they called any of this “Christianity.” He found their theology shallow to the point of being almost evaporated entirely. But he was equally alive to the dangers on the other side, the dangers of fundamentalism and pietism. He’s complicated, but in the best sense. He’s an equal opportunity theological critic.

4. You describe the process by which Germany’s Evangelical Church crumbled quickly in the face of Nazi power, toying with heretical racial theories and portraying Hitler in Messianic terms. How did Bonhoeffer understand its weaknesses? Did he view the fact that it was an established church as contributing to its vulnerability?

Bonhoeffer was not against the idea of an established German church per se, but he had a healthy awareness of its dangers. Because he had been exposed to the American churches, the idea of the separation of church and state was not foreign and unthinkable to him. He saw that it could work and had certain advantages. But he didn’t see it as a definitive answer. When the Nazis were trying to take over the German State Church, however, he saw firsthand how an established church can go wrong. When the state encroaches upon the authority of the church, the church must stand up and be the church, else it will cease to exist. It must declare itself as separate from the state. That’s what the famous Barmen Declaration was all about, and I quote it at length in the book. It drew a bold line in the sand between the church and the National Socialist state.

5. In an interview on October 18, 2010 with Brannon Howe of Worldview Radio, you said that “God called me to write the book for right now,” because the parallels of Germany then and America today are “stunning.” What exactly are the parallels that you had in mind?

Bonhoeffer talked about how the German penchant for self-sacrifice and submission to authority had been used for evil ends by the Nazis, only a deep understanding of and commitment to the God of the Bible could stand up to such wickedness. “It depends on a God who demands responsible action in a bold venture of faith,” he wrote, “and who promises forgiveness and consolation to the man who becomes a sinner in that venture.” Here was the rub: one must be more zealous to please God than to avoid sin. One must sacrifice oneself utterly to God’s purposes, even to the point of possibly making moral mistakes. One’s obedience to God must be forward-oriented and zealous and free, and to be a mere moralist or pietist would make such a life impossible.

—From Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy

Reprinted by permission of Thomas Nelson – © 2010 Eric Metaxas

There are tremendous parallels, but I didn’t see them at all until I was doing the research and writing the book. So they weren’t part of my decision to write the book. It’s only in retrospect that I felt that the call to write about Bonhoeffer had something to do with those parallels for us today. They fairly leap out from the story, so I didn’t feel any need to underscore them.

The question for Germans in the 1930s is the same question we face today. When do state concerns begin encroaching on the authority of the church to a point where the church needs to shout “halt”? If the church is healthy and is playing its role correctly, it will check the unbridled growth of the state and will protect its own members–and others, too–from illegitimate state power. Bonhoeffer wrote about this in his famous essay “The Church and the Jewish Question.” He said there were three ways that the church must behave with regard to the state. First, it must question the state. In a sense it must call the government to account, and be a voice that speaks out if and when the state is not behaving legitimately. Second, if the state is harming anyone, it’s the role of the church to help those whom the state is harming. And thirdly and most radically, if the state is behaving wrongly, it is the role of the church to directly oppose the state. That’s where he lost a lot of people. They couldn’t believe a good Lutheran German would say such a thing. But Bonhoeffer was a Christian first and a German second.

Such state encroachment usually concerns the fundamentals, such as the definition of a human being. The Nazis did not believe that human life was sacred, because they didn’t believe that human beings are created in the image of God. They were essentially pagans with a social Darwinist worldview and they began to “legally” define humanity according to this bleak, utilitarian worldview. So a German Jew was no longer a human being in the way a Gentile German was a human being. And a mentally or physically handicapped person was no longer equal to others and was therefore “disposable.” Jewish babies could be legally aborted, but German babies could not. The Nazis began to define such things in a way that aggressively challenged the beliefs of all serious Christians, so the church had to make a choice: be the church and fight the state on these issues, or accede to the state’s definitions of humanity and effectively cease to be the church. Most in the church simply acceded to the Nazi’s definitions. Those who didn’t give in formed what came to be known as the Confessing Church. Bonheoffer was one of its leaders, of course.

A related parallel has to do with Christianity itself. What is it and who gets to decide? The Nazis didn’t like certain things about the Christian faith, so they simply decided to redefine Christianity. This is always the great danger and it’s happening in our time as well. When we decide that we want to dispense with two-thousand-year-old teachings because they don’t suit us, because they strike us as old-fashioned or culturally uncomfortable, we had better be careful. One opens the door to things one hadn’t anticipated. God’s truths are eternal, or they aren’t God’s truths.

Another parallel concerns the properly Christian response to aggression and evil. Many Christians feel uncomfortable with pointing the finger at something and calling it evil, even if they feel threatened by it, but this may render them unable to confront it. Others on the opposite end of the spectrum don’t give a fig for God’s perspective and will do whatever it takes to defeat what they think of as evil. But Bonhoeffer does the hard work of asking, “What is the Christian perspective?” He saw the Nazis as evil. There’s little question of that. And he was frustrated with his fellow Christians who were uncomfortable with that idea, who were all too willing to cut the Nazis slack and continue “dialogue” with them. Bonhoeffer knew that he must confront the evil of the Nazis. The only question was how to do it. What was God saying to do?

Militant and radical Islamofascism forces us to ask these same questions. To minimize its threat is to effectively appease it, but to confront it in a way that denies the humanity of its adherents is not a Christian approach. So what is the Christian approach? Bonhoeffer trod a very lonely road in figuring this out in his day, but I think he points the way for us today. We need Bonhoeffer to help us figure this out. His warning to the church in the 1930s essentially went unheeded, but it’s my hope that today we might hear what he has to say and let it guide us toward the proper approach on this crucial issue.

6. You describe Bonhoeffer as a “prophet.” What lessons about authentic faith and political issues today would you want Americans to learn from your life of Bonhoeffer?

The main one has to do with the vast difference between mere “religion” and an actual faith in the God who made us and loves us. Bonhoeffer’s whole life is about that difference, and I think we need to hear what he has to say to us on this. His life is a picture of the difference between them, which is why I’ve written a biography and not a book of theology. To encounter a life of such beauty and courage and integrity and authenticity is inescapably inspiring. His story itself is as eloquent a statement about the meaning of life as anything I could imagine. I only hope I’ve told it in a way that does it justice.