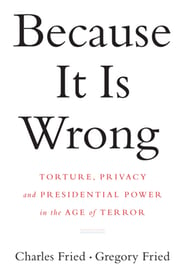

Beginning with the disclosures of Abu Ghraib and continuing over a period of several years, Reagan Administration Solicitor General and Harvard law professor Charles Fried discussed the Bush Administration’s policy choices with his son, philosophy professor Gregory Fried—forging a consensus on many issues while disagreeing on others. Now they have transformed that dialogue into a book, which presents powerful arguments against torture, accepts that the Bush Administration violated the prohibition on torture, and proceeds to a nuanced discussion of what America can do about it. I put six questions to Charles and Gregory Fried about Because It Is Wrong—Torture, Privacy and Presidential Power in the Age of Terror:

1. Your book opens with a discussion of Leon Golub’s Interrogation 1 and continues with references to a number of other masterworks of graphic art. How did you pick the art, and how does it help you address the ethics issues covered in your book?

charles fried: To treat works of art as mere illustrations, or substitutes for arguments, demeans them as art, as works that speak for themselves and raise questions of their own. In working on this book, one thing we hoped to achieve was to write for an audience broader than merely academic scholars; we felt that the questions we were addressing go to the heart of what our nation stands for, and so we tried to make articulate what our moral intuitions on these issues are. Formal arguments are not very good at evoking deeply held moral intuitions. This is why we turned to art as well as to religious stories and to history: we wanted to appeal to images and to tales that we believed many, if not most, of our readers would find familiar. We hoped to make an argument that would find resonance with deep traditions the American people would understand. Art, stories, and intuition cannot substitute for reason, but they are an introduction and accompaniment to reason, helping to overcome objections where reason alone may not persuade.

gregory fried: Some readers have told us that they were put off by our use of biblical stories and religious concepts, such as the notion of human beings as created in the image of God. I think we should underline that in a book addressed to the general American public, we endeavored to find cultural reference points to the core moral intuitions we wanted to emphasize. It is striking that the response of some to any biblical reference would be so allergic and reactive. That may say something about the passions surrounding the debates over religion today; however, we do not think one must be religious to understand the ethical point of the imagery or stories. That would be narrow-minded indeed. Although perhaps one serious question here is whether the idea that there is something sacred about the dignity of the human person is ultimately a religious notion, whatever a secularist or atheist might believe about that dignity as grounded in purely humanistic values.

2. The book moves from torture to questions of privacy. You both seem agreed that torture is an absolute wrong, as the title suggests, but that surveillance may be absolutely justified with the right circumstances and procedures. What led you to pair torture and privacy as issues?

The common good requires that

we find out who commits acts of injustice and why, so that

injustice can be prevented or cured and the unjust punished.

We know that the facts and the criminals do not willingly

announce themselves, and so we must pry them out. But even

beyond that and descending to the level of gossip and idle curiosity,

sociability—the conditions of common life—entails (if it

does not require) that we attain some, perhaps only minimal,

level of familiarity with each other, that we take some interest

in each other, even in the people we pass on the street or

sit across from on the subway…. It is as if we owe each other

some minimal level of self-revelation. So privacy is surely a

value and an intrinsic one, but it is not even plausibly an absolute—

unlike, as we have argued, the prohibition on torture.

—From Because It Is Wrong—Torture, Privacy and Presidential Power in the Age of Terror

Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton & Co.- © 2010 Charles Fried and Gregory Fried

charles fried: Torture and surveillance are used to get information about potential threats, and the government broke the laws prohibiting or regulating both in its efforts to prevent another attack after 9/11. The general public, and even the informed public, reacted as if both transgressions were equally serious and equally deserving of condemnation. Indeed, there may have been a markedly greater tolerance of torture than of surveillance—maybe because few of us expect to undergo torture, but all feel our phones or Internet may be tapped into. This gets things exactly wrong. It is morally obtuse, an example of law fetishism, to equate the two just because they are both illegal. Torture is illegal because it is wrong and electronic surveillance is wrong—when it is—because it is illegal.

Privacy is a moral and legal value; but it is contingent and custom-bound. After all, the Fourth Amendment speaks of “unreasonable searches and seizures” and the need for a warrant. There is no such thing as reasonable torture, and torture warrants would be an abomination. This is not to say that there should not be some secure zone of privacy to which citizens may, ordinarily, turn in order to think, act, and commune with one another without fear of scrutiny. There absolutely should be such a zone of privacy, but its borders are not absolute, neither as to where they are drawn nor in being impermeable.

3. It’s often argued that if law and ethics allow you to kill an enemy in wartime, it must also allow you to torture him. What’s the matter with this argument?

charles fried: Behind the argument in this question lies the assumption that survival trumps all other values, and that therefore whatever we reasonably believe we need to do to survive is legitimate. This is a way of bringing torture in through back door. The permission to kill in warfare derives from the permission to kill in self-defense. That is why when an enemy surrenders or is hors de combat because of wounds, the law and ethics of war strictly forbid killing him. Killing disables someone who is seeking to kill me. Torture may be a defensive response, but it is one that destroys not the person but the humanity of the person. We will all die, so mortality does not impugn our humanity. Brute survival is not the highest end.

gregory fried: We should be alive to the question of what we survive as. We are mortal, we cannot live forever, and we have the freedom to choose to live, not merely to survive, according to principles that we believe make life worth living. And we have to have the courage to live according to those principles, not to discard them when it seems convenient. To paraphrase Judge Aharon Barak, for a democracy to remain a democracy, it must sometimes fight with one hand tied behind its back — we must not use all the tools that might be available to us to defeat an enemy if some of those tools undermine the core principles that govern our own political and civic life. We would argue further that fighting this way, without resorting to torture, will in fact make us stronger, because it upholds the convictions that define us as a free republic by respecting the fundamental dignity of all persons, even the worst ones. Just as we expect soldiers to display courage in war, to risk their lives in a cause, we must ask for a similar courage from all citizens of a free country: to renounce tools of war and interrogation, such as torture, that seem to promise increased safety, but which in fact constitute a poison pill for democratic values.

4. You argue against “Machiavellian heroes” while recognizing that Machiavelli’s arguments carry much weight. Instead you ask us to look at Nelson Mandela as another sort of hero. What guidance does Mandela give us in forging a new moral consensus about torture?

charles fried: We do not need a new moral consensus. We have the old one, which is good enough. Lincoln in 1863 promulgated the first code for the conduct of warfare. That code acknowledged the necessity and propriety of killing and wounding enemy combatants in warfare, and even in proper proportion innocent bystanders. But “cruelty” and “torture” were strictly and always forbidden. That is what our officers have been taught for generations—it is part of the honor of being a soldier. We are not aware that Mandela is a model in the fight against torture: he is a model of humanity and the virtue of reconciliation.

What is truly shocking about our current situation is that we find otherwise respected politicians and opinion leaders in the media arguing for practices of “enhanced interrogation” that just a decade ago would have been unthinkable and unequivocally denounced as what they are: torture. Whether this is a result of the panic following 9/11, television shows such as “24,” or some other combination of factors is a question best left to cultural historians. But the fact remains that this open and high-level embrace of torture is a sudden and profound departure for the United States. So opposing it is not a matter of a new consensus but rather a renewed one.

gregory fried: Mandela’s example serves as a model, not for the question of torture specifically, but rather for what constitutes genuine statecraft. When he came to power in South Africa in 1994 after the fall of apartheid, Mandela understood that however important good laws and a new constitution may be, they are meaningless if the people do not share a sense of common commitment to the core principles of the nation. That is why Mandela insisted that not just the former ruling National Party but also his own African National Congress must admit its violations of human rights in the truth and reconciliation process. That is why he took so seriously the whole country uniting behind the national rugby team, the Springboks, as a symbol of racial unity and equality (as portrayed in the wonderful film Invictus).

The rule of law, which is so crucial to free republics, cannot be upheld by law itself; it requires the united commitment of the people to democratic principles such as human dignity. When leaders embrace techniques such as torture for short-term gain, they forget a key lesson of statecraft, which is that radical departures from foundational principles, no matter how useful they might appear at the moment, can result in lasting changes to the living character of a people and its government. We mull over torture as a response to ticking time-bomb hypotheticals and we consider the use of torture warrants, but we forget that actual human beings must carry out such measures. What will it do to our character as a people, to our courts, and to the nature of our government generally if we institutionalize the art of torture? Can America remain unchanged if we have schools dedicated to instructing and practicing torture? If we cultivate a class of officials committed to torture as their career? What spirit will they take home with them, to their families and communities, at the end of the day? There is not only the victim of torture to consider, but also the moral devastation of the torturer. And in public discourse and popular culture, won’t we be asked to embrace such new institutions as a positive good (witness the show “24” already), not just a necessary evil? And so the corrosion will spread. Torture, as we say in the book, is the practice of tyrannies; it cannot just be picked up and put down like a socket wrench, as if it had no lasting impact on those who wield it.

5. Gregory makes the case for accountability for high government officials who authorized torture, while Charles expresses caution based among other things on the politically destabilizing effect a prosecution might have. In Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, governments refrained from bringing torture charges against their predecessors for several decades for just the reasons Charles suggests, but in the last decade charges have finally been brought—generally with very broad public support. Are these examples instructive for America?

Torture is the habit of tyranny, not of

free republics, and it cannot simply be switched on and off. It

inculcates a conception of state power and human worth that

directly conflicts with our founding principle of an inalienable

dignity to the human person, even the most culpable.

As we know from Abu Ghraib, once it is unleashed, even

as a supposedly well-quarantined tactic practiced by putative

professionals, torture spreads like cancer…. This is the lesson of

history for all governments that turn to torture: an isolated

practice expands to become the emblem of state power and

the reality of the citizens’ subjection.

—From Because It Is Wrong—Torture, Privacy and Presidential Power in the Age of Terror

Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton & Co.- © 2010 Charles Fried and Gregory Fried

charles fried: While I am not an expert on the recent history of those countries, I would say that in these cases, the victims were overwhelmingly the fellow citizens of their torturers. There were also very many victims. So the transgressions in those nations were massive and carried out by dictatorial regimes against their own people. I think this combination of factors meant that those nations simply could not move forward without some kind of accounting. But the sad fact is that the victims of torture in the case of the War on Terror are overwhelmingly foreign nationals, and so it is unlikely there will be a similar pressure for transitional justice as in the cases you cite. This is not a justification, just a prediction.

gregory fried: If the point of the question is that prosecutions may have to wait until a time when passions have cooled and the political landscape has changed, that may well be; but it certainly seems that in the United States, the cooling of passions also means the forgetting of the past, especially if the victim was a feared and unfamiliar Other with whom Americans feel little personal connection; the opposite must have been the case for citizens in those Latin American nations, who knew both perpetrators and victims intimately. So I don’t see much hope that the passage of time will result in prosecutions in our country, unless we succeed in making vivid for our own people the nature of the crimes committed. This would be an argument for congressional hearings, but that seems rather unlikely after last November’s elections.

6. Professional ethics for lawyers, physicians and psychologists provides a regime for accountability apart from criminal law. In Texas, the State Board of Psychology has just decided to take up ethics complaints against a licensed psychologist who allegedly was involved in devising and implementing waterboarding and other “enhanced interrogation practices” for the CIA. Is this sort of professional discipline appropriate even where criminal justice measures might not be?

gregory fried: It might well be, but as the question indicates, such actions tend to apply to relatively low-level participants in the apparatus of interrogation and torture. As such, while this might do some work in repudiating torture, such disciplinary action by no means does so on a national level, and therefore it remains ambiguous and hardly decisive.

Still, this sort of professional discipline may now be the only realistic option, at least within the confines of the United States, to lay down some kind of marker that these practices are unacceptable. It has become increasingly clear that the political will is lacking to conduct either prosecutions or congressional hearings on torture. Outside of the United States is another matter, and it may well be the case that figures such as Donald Rumsfeld and John Yoo, and perhaps those even higher up in the chain of command, will have to think twice about traveling abroad, where they might be arrested and put on trial for war crimes.

That would be a terrible situation for the United States, not only because it would be a diplomatic disaster, but also because it would underline the fact that we as a nation have been unable, by ourselves, to come to terms with this departure from our long-standing traditions in law and in principle. At a time in our history when we are conducting military occupations to bring democracy to previously autocratic regimes, this would be a sad irony indeed.