Sollte aber Ihr ehrliches, durch mehrfache Proben bewährtes Streben Ihnen mit Entschiedenheit besondere, von den bisherigen abweichende Wege weisen, dann—folgen Sie Ihrer eigenen Überzeugung mehr als jeder anderen. Denn diese ist und bleibt Ihr höchstes, köstlichstes Gut, so gewiß als die Heranbildung zur wissenschaftlichen Selbständigkeit das schönste Ziel des akademischen Unterrichts bildet, und so gewiß eine in redlicher Arbeit erworbene eigene wissenschaftliche Überzeugung einen festen Ankergrund angibt, um auch der sittlichen Weltanschauung allen den möglichen Wechselfällen des Lebens gegenüber den nötigen Halt zu gewähren.

Die edelste unter den sittlichen Blüten der Wissenschaft und zugleich auch ihre eigentümlichste ist ohne Zweifel die Wahrhaftigkeit, die durch das Bewußtsein der persönlichen Verantwortung hindurch zur inneren Freiheit führt und deren Wertschätzung in unserem gegenwärtigen öffentlichen wie privaten Leben noch viel höher bemessen werden sollte.

But if you see a different way, one that differs from the path most trodden but has been decisively tested through honest and diligently proven methods, then–follow your own convictions and not those more commonly shared. This is and remains your highest, most valuable possession, for the development of scientific independence is the most beautiful goal of academic training, and a scientific conviction gained through honest work provides a firm anchoring from which you can maintain an essential independent perspective even with respect to the moral foundations of society and all other changes you may face in life.

The noblest of man’s moral qualities and also its most characteristic is without doubt truthfulness: that fidelity to truth, through an awareness of personal responsibility, leads to inner freedom. It deserves to be held in far higher regard in our current public and private life.

—Max Planck, “Neue Bahnen der physikalischen Erkenntnis,” speech delivered on Oct. 15, 1913, reproduced in Physikalische Abhandlungen und Vorträge, vol. 3, p. 75 (1958)(Fritz Stern/S.H. transl.)

Reading through Saul Bellow’s entertaining novel-memoir of Allan Bloom, Ravelstein, I was struck by this passage: “Ravelstein… held that examples of great personalities among scientists were scarce. Great philosophers, painters, statesmen, lawyers, yes. But great-souled men or women in science were extremely rare. ‘It’s their sciences that are great, not their persons.'” (p. 107) The observation is both extremely telling and dead wrong. Bloom, like his mentor, Leo Strauss, and a number of other figures associated with neoconservatism, has a tough time with scientists, with scientific method and with science. They can’t reject it, of course, and they can’t deny the importance of science to society and human development. But they often feel uncomfortable with it, particularly when it picks at the margins of their cherished political ideas, and they bristle over the notion of taking direction from scientists. Bloom/Ravelstein suggests in this passage that they might accept the science itself as important, but not the scientists. The voice of scientists should be pushed to the sidelines–they are not the “great souls” that speak to us across the ages.

Really? Of course it’s true that scientists as a group aren’t the hero-worshipping kind and most would smirk at the label “great soul.” But what of Pythagoras, whose now lost writings exercised such a heavy influence on Bloom’s hero Plato? What about Kepler, Galileo, Newton, Einstein and Sakharov? Were they not all “great souls”? Did they not have much to say to humanity over the ages? Are their voices still not powerful?

In America today, nutty conspiracy theories appear in our broadcast media with some regularity and now it’s no longer just individual scientists but science itself which seems to have become the target of sustained political attack. To some extent, these phenomena are common to times when societies are under pressure—when unemployment is high and politics is fractious. Science has always been taken as a threat to those who hold simple ideas with religious fervor and take comfort from the belief that they explain everything–and to the politicians who attempt to manipulate them. A prominent Fox television host insisted this week, with growing vehemence, that tides are proof positive of the existence of God. Modern science offers perfectly sensible explanations for the presence of tides; but the sensitivity is an ancient one, figuring in the questioning of Galileo by the Inquisition in 1633. As recently as 1990 the current pope was struggling to justify what his predecessors had done on this score. Still, there is no logical reason why the scientific explanation for tides should be taken as disproving the existence of God–no more than the fact that the we live in a heliocentric planetary system proves that God is Dead. (It does, however, decisively disprove the Ptolemaic model adopted by Aristotle and the early church fathers.) Much of the controversy between science and faith is nonsense; and much of it is driven by religious figures for whom the love of dogma has come to supplant the dogma of love.

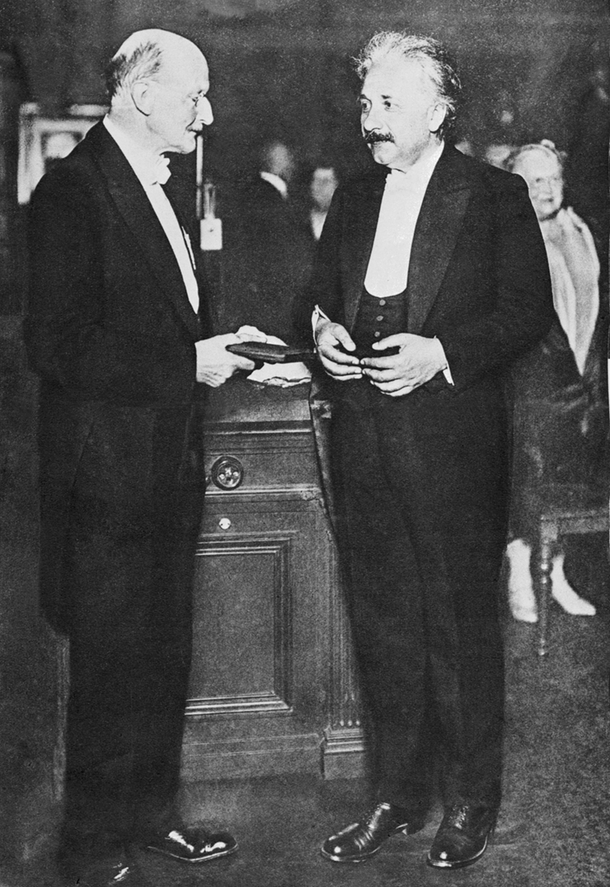

But conspiracy theories and anti-scientific quackery in America today are nothing compared with what raged in Central Europe in the years between the two world wars. That overlapped with some of the great scientific discoveries of the modern era, and a disproportionate share of that work was done in the universities and laboratories of Central Europe. As we learn from Fritz Stern in Einstein’s German World, the great men of science of this era—Albert Einstein, Max Planck, Paul Ehrlich and Fritz Haber in the first echelon—were by and large outsiders to the world of politics. For the most part they were proud of the accomplishments of the Wilhelmine era, but their pride focused more on their universities and research institutes and less on the Kaiser. In the face of a storm of political craziness, xenophobia and hysteria, they had remarkably similar advice to dispense to their students and to society in general: keep your own counsel and don’t get caught up in the tumult of mobs and the delusion of conspiracy theorists.

Einstein was typical, furnishing this advice to an unemployed musician from Munich in 1933: “Read no newspapers, try to find a few friends who think as you do, read the wonderful writers of earlier times, Kant, Goethe, Lessing, and the classics of other lands, and enjoy the natural beauties of Munich’s surroundings. Make believe all the time that you are living, so to speak, on Mars among alien creatures and blot out any deeper interest in the actions of those creatures. Make friends with a few animals. Then you will become a cheerful man once more and nothing will be able to trouble you.” Regrettably, of course, his musician would not have gotten far with such practices in the world that was then opening up around him. Einstein himself did the right thing: taking measure of the grave threat that the rise of fascism presented to the world, he became increasingly active and increasingly vocal in opposing it. Other scientists of the era kept quiet, and their historical reputations suffered for it.

But there is no finer statement of the scientist’s calling and of the essential commitment to truth that lies at the heart of great scientific work than can be found in this speech that Max Planck delivered to an incoming class of students at the University of Berlin in the fall of 1913. Trust less what you are told and more what you observe, test and confirm for yourself, he says. If our society is to prosper in peace and happiness, then the precepts of science must occupy their proper place, and none of them is more powerful than this rigorous commitment to truth, whether it conforms to the prejudices of the masses or not. Scientists bring technological innovation that can make our lives easier and more meaningful; but when they warn us of threats on the horizon, we ignore them at our own great peril.