?????? ?? ? ???????? ????? ??????? ??????, ?????? ??? ??? ??? ??? ???? ?????????? ???? ????? ????? ????????, ??? ????????? ?????? ?? ????????? ??? ???????? ????: ?????? ????? ??? ??????? ???? ??????????? ?? ?????, ??? ???????? ??? ??????? ??? ????????? ??? ???????? ??? ??? ?? ??? ?????? ??????. ???? ?? ??????????????? ???? ????? ???????? ????? ????????, ?????? ?? ??? ????: ????????? ??? ??? ??? ?????? ??? ?? ??????? ????? ???????????? ?????, ??? ? ??????????? ????? ?????? ???? ??? ?????? ????? ?????? ??, ???? ?? ??? ??? ?????? ??????? ?????? — ????????? ??? ?????? ???? ?????, ?? ????? ???????? — ??????? ?? ??????????? ??? ???????? ????????? ??????: ??? ??? ???????????, ??????? ???????? ??? ??? ??????? ??? ????????? ??????, ???? ????? ????????????? ????????????.

???? ??? ?????? ???? ?? ????? ???? ?? ???????? ???, ????? ?????? ?????? ??? ????????? ???? ?? ??? ?????, ??? ???? ?????? ?????? ?? ??? ?????? ?????? ?????????. ????? ??? ????? ??? ???? ??? ?????? ???? ????? ??? ???? ?????????: ‘??????? ?? ?? ?????? ??????????, ???? ??? ?????? ?????; ?????????? ?? ???: ??? ???? ???????? ??????? ?????? ????????, ??? ?? ????? ??????????: ??? ????? ?? ??? ???? ’ ???? ?? ?? ???? ?????????, ? ??? ?????? ?????;’ ‘??? ??????,’ ??? ? ????, ‘??? ?????? ??????????: ?? ??? ?? ???????? ??????, ?? ?????? ????? ????????? ????? ????? ??????: ??? ????? ?? ??? ???? ???? ??? ?? ????????? ?????? ??? ????? ???????? ???????? ?? ????? ??????.’

???? ??, ? ????????, ??? ??? ????? ?? ?? ????? ??? ????????, ???? ??? ???? ?????? ?????????? ? ????? ? ????? ????? ????????????, ??????? ??????? ???????? ?????????, ??? ??? ??? ????? ?? ??? ?????? ??????????, ??? ?????????, ?? ?? ???—???????, ?? ??? ????—???? ?? ??? ????????? ????????? ?????? ?????, ?? ??? ??? ??????????? ????? ????? ??? ??????????, ??????? ??????? ?????? ?????????, ?? ????? ???????? ?????? ?? ???????? ??? ?????? ? ?? ????? ??????. ????, ? ????????, ?????? ?????.

And now that man was partaker of a divine portion, he, in the first place, by his nearness of kin to deity, was the only creature that worshipped gods, and set himself to establish altars and holy images; and secondly, he soon was enabled by his skill to articulate speech and words, and to invent dwellings, clothes, sandals, beds, and the foods that are of the earth. Thus far provided, men dwelt separately in the beginning, and cities there were none; so that they were being destroyed by the wild beasts, since these were in all ways stronger than they; and although their skill in handiwork was a sufficient aid in respect of food, in their warfare with the beasts it was defective; for as yet they had no civic art, which includes the art of war. So they sought to band themselves together and secure their lives by founding cities. Now as often as they were banded together they did wrong to one another through the lack of civic art, and thus they began to be scattered again and to perish.

So Zeus, fearing that our race was in danger of utter destruction, sent Hermes to bring respect and right among men, to the end that there should be regulation of cities and friendly ties to draw them together. Then Hermes asked Zeus in what manner then was he to give men right and respect: “Am I to deal them out as the arts have been dealt? That dealing was done in such wise that one man possessing medical art is able to treat many ordinary men, and so with the other craftsmen. Am I to place among men right and respect in this way also, or deal them out to all?” “To all,” replied Zeus; “let all have their share: for cities cannot be formed if only a few have a share of these as of other arts. And make thereto a law of my ordaining, that he who cannot partake of respect and right shall die the death as a public pest.”

Hence it comes about, Socrates, that people in cities, and especially in Athens, consider it the concern of a few to advise on cases of artistic excellence or good craftsmanship, and if anyone outside the few gives advice they disallow it, as you say, and not without reason, as I think: but when they meet for a consultation on civic art, where they should be guided throughout by justice and good sense, they naturally allow advice from everybody, since it is held that everyone should partake of this excellence, or else that states cannot be.

—Plato, Protagoras, 322a–323a (433 B.C.E., W.R.M. Lamb, trans.)

Can virtue be taught? That is the subject of the Platonic dialogue from which this passage is drawn. Socrates is squaring off here against his somewhat older rival Protagoras. It’s predictable Platonic material, grounds for endless and indeterminate debate.

Midway through the dialogue, things take an interesting turn. Protagoras argues that in the polis, the views of all citizens are worthy of attention, and he offers as support what can only be called a democratic creation myth. The beginning of his tale looks like the usual Prometheus story. But then he adapts it to his purpose. After receiving their first set of gifts, Protagoras says, men still did not seem capable of living with one another; nor were they able to build cities or wage war. They lacked what W.R.M. Lamb translates as “the civic art.” The original Greek is ????????? ??????, for which the contemporary English cognates would be “political technique.” But it takes some scrambling to elaborate this: “political” in the Greek sense would relate to social interaction — so not to politics as it appears in newspaper reportage today. “Technique,” meanwhile, would refer to all the arts, skills, and crafts that humans are capable of acquiring through inductive reasoning.

In Protagoras’s account, the gods’ remedy for the human shortcoming in civic art is two further gifts. One is ?????, which Lamb renders as “respect,” and which indeed involves a concern for the positive opinion of others, but which might equally be rendered more negatively, as a sense of shame. The other gift is ????, which Lamb calls “right,” but which might better be described as the spirit of moral justice. So the skills that are essential to turning man into a political animal are these: a sense of concern for the feelings and opinions of others, and a sense of justice as an abstract and moral concept.

Just as important, though, is the question of endowment. Who receives these gifts? The answer is all humans. Not simply the elites. Not simply the members of one polis, and indeed not even just the Greeks, though they are surely the people of antiquity most conscious of these gifts, and most intent on unlocking them.

Protagoras goes on to draw out the message of his legend: While it’s true that cities turn for guidance to the opinions of persons possessed of certain special skills, when it comes to the ????????? ?????? — to the political arts; which is to say, when the question at hand is one of governance — all citizens need to be consulted. If the people of the cities are guided throughout by justice and good sense, he says, “they naturally allow advice from everybody, since it is held that everyone should partake of this excellence, or else that states cannot be.”

To be sure, the voice we hear in this passage is neither that of Socrates, nor his student Plato — elitists who doubt profoundly the wisdom of the masses, and who disdain democracy. In the course of the dialogue, Socrates struggles to conceal his contempt for the idea that carpenters and fishermen could have something useful to say about important matters of state. He would rather see rule by a dictatorial philosopher-king. But in the lines Plato composes for Protagoras, we hear the spirit of Athenian democracy, as well as its basic premises: acceptance of the fundamental worth of all citizens, and faith in democratic process.

Protagoras’s words provide an important foil when contemplating the progress of American democracy. During the golden age of Athenian democracy, when Protagoras was written, decisions concerning collective security belonged to the democratic franchise. A popular assembly would deliberate not only whether war was to be waged and who would be placed in command, but tactics, punishments, and the treatment of allies and foes. Generals and admirals who failed to perform their missions, or even whose victory was tempered by an offense against the dignity of the fallen, would be called to account.

America has always been a representative democracy, rather than a direct one, but at the time of the country’s founding, decisions about national security were divided between the legislative and executive branches in hopes of promoting broad popular discussion and achieving national consensus on important issues. Over the past few decades, however, the public space for discussion and participation in national-security decision-making has steadily narrowed. In Protagoras’s terms, political art has succumbed to the dark magic of the technician.

The arguments for an executive monopoly are by now familiar: only national security “experts” are said to have the skills and the information necessary to make judgments about collective security. The uninformed public cannot be entrusted with the right to decide its fate. And yet, the same people making these arguments routinely classify basic information, thereby ensuring the public is kept uniformed. Such secrecy suffocates democracy. Judgment about matters once viewed as the essence of the democratic franchise has passed into the hands of a murky and unelected class of elite technocrats — civil servants with high-level security classifications — who alone make the vital decisions that affect the security of the state, decisions that are often matters of life and death for their fellow citizens and others. Protagoras suggests for us a question: Is such a system really a democracy? And is it a state that respects the abilities and rights of its citizens?

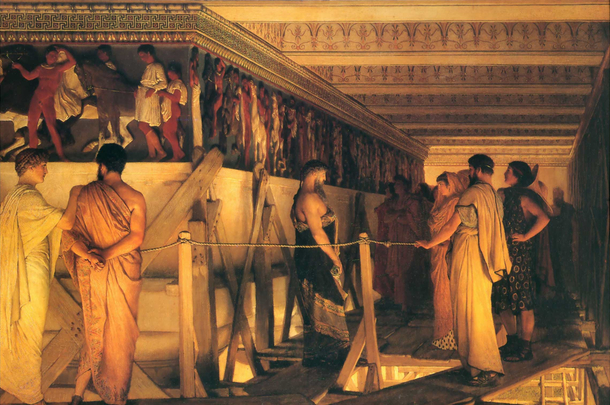

The Dutch painter Laurence Alma-Tadema (who later moved to England, was knighted, and became a member of the Royal Academy) was one of the more striking and profound nineteenth-century chroniclers of classical antiquity. In this painting, the master architect Phidias is exhibiting his work, specifically the frieze of the Parthenon, to a select audience, among them figures who appear in Protagoras: Socrates, Plato, Alcibiades, and Pericles. Anthropomorphized depictions of ????, the goddess of moral justice, appear in the Parthenon’s ornamentation.

In 1788, the Oxford musicologist Philip Hayes composed a remarkable round for the text of Psalm 137, entitled “By the waters of Babylon.” It speaks of the pain and suffering of a people held in bondage, and their longing for freedom and return, and it gained instant popularity for its simplicity and perfection of expression, emerging as an anthem of the anti-slavery movement in Hayes’s lifetime and the decades that followed. It has become better known in recent times thanks to a performance by Don McLean: