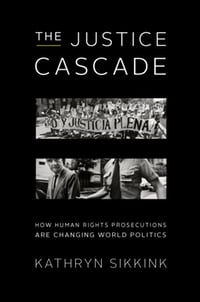

Kathryn Sikkink has spent thirty-five years studying how nations hold their leaders to account for such crimes as kidnapping, torture, and extrajudicial execution, which are often committed against the backdrop of civil insurrection, war, or antiterroism campaigns. The conclusions she draws are startling: in place of historical doctrines of immunity, a new trend she dubs the “justice cascade” is pressing national criminal-justice systems and international law toward greater accountability. I put six questions to Sikkink about her study, as well as her opinion on what the justice cascade means for American leaders who adopted practices that in other nations led to demands for accountability.

1. You start your work by examining the collapses of brutal military dictatorships in Europe’s southern tier (Greece, Spain and Portugal), and point out that although political and social processes led to accountability in Greece and Portugal, they didn’t in Spain. Will accountability for the horrendous crimes of the Franco period be avoided forever, or have they merely been delayed?

Based on charges filed by associations of victims and their families, Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzón opened an investigation in 2008 into more than 100,000 cases of executions and disappearances that took place from 1936 to 1951. So, we are talking here about executions and disappearances that happened between sixty and seventy-five years ago. My book is about the trend toward individual criminal accountability, which requires that cases be brought against specific living perpetrators. Virtually all of the suspected perpetrators in Spain are now dead. Although individual criminal accountability for human rights violations from that period is no longer possible, other forms of accountability are needed. In particular, many family members still hope to locate the remains of their relatives, to rebury those remains, and to know more about the circumstances that led to the deaths. Such truth-telling is still necessary and possible, even if individual criminal accountability is not.

2. Samuel Huntington wrote that if accountability trials were to be conducted, they had to occur immediately in the wake of transition or not at all. His view seems to have been the received wisdom of political scientists twenty years ago. Have the intervening events tended to sustain or to refute him?

The single most forceful finding of my research is that on this issue, Huntington was completely wrong. Justice comes slowly — often painfully, unacceptably slowly in the eyes of victims — but surprisingly it often does come. Domestic courts in Uruguay took twenty years to sentence former authoritarian leaders Juan María Bordaberry and General Gregorio Álvarez for ordering the murders of political opponents. The Extraordinary Chambers in Cambodia issued its first conviction last year, more than thirty years after the horrors of the killing fields.

The most interesting evidence from my research, though, shows not that justice is occurring even after many years, but that prosecutions appear to deter future human rights violations. A careful statistical analysis of all such cases in transitional countries shows that those who prosecute offenders are more likely to see improvements in human rights. I believe this means that since human rights prosecutions increase the perceived likelihood of punishment, they deter potential repressors from killing or torturing their opponents.

3. In Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, nasty dictatorships gave way to democracy under circumstances in which the culprits secured some form of amnesty or immunity. Yet in none of these countries did those arrangements hold up over time. Why?

There were very large numbers of victims in all of these countries, who provided the backbone for well-organized human rights movements that worked hard for accountability. They eventually got help from their own judicial systems and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. These activists were incredibly persistent and ingenious in finding legal ways to undermine or circumvent the amnesty laws.

Since I sent my book to press, new developments in the Southern Cone of South America have continued to reveal the persistence of human rights advocates. In Argentina, one of the most notorious perpetrators, former naval officer Alfredo Astiz — the so-called “angel of death,” who infiltrated the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and caused the disappearance of some members of that group — was found guilty of torture, murder, and forced disappearance, and sentenced to life in prison. And Brazil, the only transitional country in the region that had not seen any human rights prosecutions for violations committed during the authoritarian regime, decided to set up its first official truth commission to examine events during its authoritarian period. Also, this October, Uruguay’s parliament derogated the country’s long-standing amnesty law and declared the crimes of its past dictatorship to have been crimes against humanity. I think what carried the day was the deep outrage of many young Uruguayans, some of whom weren’t alive when the events occurred, yet who asked how powerful individuals who had ordered the murders of Uruguayans could be sheltered from prosecution.

4. While you build an impressive case for the triumph of accountability principles across Europe and Latin America, and in many other nations around the globe, the United States in the era of Bush and Obama seems to be a stubborn outlier. What has happened in America that puts this country on a course so sharply at odds with most of the world, and in particular with our allies?

Although demands for justice have been remarkably resilient, it has not been easy for any country to confront its past. Almost all leaders, faced with the dilemmas of accountability, have wanted to turn the page and look toward the future. Even in countries like Greece and Argentina, which have seen strong popular demand for accountability, leaders faced agonizing choices that they feared could lead to military coups. As the United States confronts the legacies of the Bush Administration’s human rights violations, it will help to remember that countries with far weaker political and judicial systems have nevertheless managed to hold their leaders accountable.

The U.S. military has prosecuted a series of cases involving soldiers engaged in the abuse of detainees, but the definition of torture in the UN Convention against Torture looks beyond those who actually inflict pain, to officials who instigate, consent to, or acquiesce to torture or cruel and degrading treatment. To date, almost all of the investigated military personnel have been enlisted soldiers, not officers, and no U.S. military officer or civilian official has been held accountable for criminal acts committed by subordinates. As I document in my chapter on the United States, we are unlikely to see further moves toward domestic criminal accountability, because U.S. officials during the Bush Administration did everything possible to protect themselves from prosecution. But while legislation might protect U.S. officials from domestic prosecution, it cannot necessarily protect them from foreign courts, such as those of Italy, whose courts were the first to convict U.S. citizens for crimes committed as part of the war on terrorism during the Bush years.

The interesting question is whether the lack of criminal accountability for higher-level U.S. officials will eventually lead to more attempts at foreign criminal prosecutions. With the exception of the case in Italy, foreign prosecutions against Rumsfeld and other officials have not succeeded, in part because foreign judges have accepted claims that the United States is making efforts at accountability. Two civil cases against Rumsfeld for torture are now moving ahead in U.S. courts, so I think they will be very important in establishing whether some form of accountability for higher-level officials is possible in the U.S. judicial system.

5. As you describe it, the development of an International Criminal Court with an independent, autonomous prosecutor was largely opposed by the United States. Today, Hillary Clinton has maintained a formally ambiguous view of the court, but she has pushed to see key matters, such as the cases against Muammar Qaddafi and Bashar al-Assad, placed under its control. Does this suggest to you a growing reconciliation of the United States to the ICC concept?

The United States has reconciled itself to the ICC concept in the sense that we are now willing to use it to pursue certain foreign-policy objectives, like the indictment against Qaddafi. But we have not changed our position about a court with an independent prosecutor to the extent of being any more willing or able to ratify the Rome Statute and submit ourselves to the ICC’s jurisdiction. I don’t expect to see U.S. ratification any time in the near future.

6. While your book was with your press, the Arab Spring erupted, building off of demands for human dignity and an insistence on the principle of accountability for torture and crimes against humanity. Many (notably in the CIA) had predicted that such a shift was impossible. Do you see the Arab Spring as further validation of ideas about the justice cascade, particularly of the notion that individual human actors and NGOs, and not just states, are in a position to drive this process?

Yes, I believe that the demands for accountability in Egypt, Tunisia, and elsewhere in the Arab world are evidence for the justice cascade. This concept measures the increase in the legitimacy of the norm of individual criminal accountability — so the fact that protestors in Egypt immediately demanded accountability for Mubarak underscores how the legitimacy of such demands has increased. But my research also suggests that accountability will not come easily in the Middle East, in large part because it has not been easy in any part of the world, including places with longer democratic traditions and better-functioning judicial systems. The number of human rights prosecutions around the globe has grown dramatically in the past twenty years, but in no case have they occurred smoothly and without delays, pushback, and unexpected legal maneuvering. Delay has often been the rule, not the exception. So the “advice” I might give to the human rights activists in the Arab Spring is this: You must know that justice takes time, often too much time, but that it is possible. Expect delays and disappointments. But only if advocates of justice do not tire nor relent, not only in your country, but elsewhere in the world, will accountability be realized.