Les loix naturelles et fondamentales des sociétés sont la règle souveraine et decisive du juste et de l’injuste absolu, du bien et du mal moral, elles s’impriment dans le cœur des hommes, elles sont la lumière qui les éclaire et maîtrise leur conscience: cette lumière n’est affaiblie ou obscurcie que par leurs passions déréglées. Le principal objet des loix positives est ce dérèglement même auquel elles oposent une sanction redoubtable aux hommes pervers: car en gros de quoi s’agit-it pour la prospérité d’une nation? De cultiver la terre avec le plus grand succès possible et de preserver la société des voleurs et des méchans. La première partie est ordonnée par l’intérêt, la seconde est confiée au gouvernement civil. Les hommes de bonne volonté n’ont besoin que d’instructions qui leur dévelopent les vérités lumineuses qui ne s’aperçoivent distinctement et vivement que par l’exercice de la raison. Les lois positives ne peuvent suppléer que fort imparfaitement à cette connaissance intellectuelle, leur injonction trop servilement assujettie à la lettre interdit plus aux hommes l’usage de la raison qu’elle ne les instruit.

The natural and fundamental laws of societies are the sovereign and decisive rule of the fair and of absolute injustice, of moral good and evil, they imprint themselves on the hearts of men, they are the light that illuminates and masters their conscience: this light can only be weakened or obscured by their disordered passions. The principal objective of positive laws is this very disorderliness, to which they oppose a severe punishment to those perverse men. For, on the whole, what is it that is truly necessary for the prosperity of a nation? To cultivate the land as successfully as possible and to keep society safe from thieves and rogues. The first part is governed by self-interest, the second is entrusted to the civil government. Men of good will have need only of guidance which these luminous truths, which are perceived distinctly and vividly only by the exercise of reason, will provide them. Positive laws provide very poor substitutes for intellectual understanding given that their servile subordination to the literal text inhibits men from using their reason more than it educates them.

—François Quesnay, “Despotisme de la Chine,” first published in Éphémérides du citoyen (1767), reproduced in Œuvres économiques complètes et autres textes, pp. 1016–17 (2005)(S.H./B.H. transl.)

When Thomas Paine wrote in Common Sense that “in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other,” and when John Adams wrote the same year that “good government is an Empire of laws,” they were both echoing language that had been honed and developed in prior decades by the French authors of laissez-faire capitalism. François Quesnay may have been chief among them. In conversation with the Dauphin in 1752, for instance, Quesnay denied the Dauphin’s suggestion that the king’s duties were burdensome, insisting instead that the sovereign need do nothing but allow the law to rule. In a properly functioning monarchy, the king was little more than an ornament; the law and organs of justice administered a country whose subjects were free to pursue their own economic interests, within certain limits.

No doubt, these ideas influenced the Bourbon monarchy in the second half of the eighteenth century and led to the improvement of classes that were already propertied and industrious. But we have good reason to question whether their effect was universally positive.

At the time of the American revolution, the concept of the dominance of laws over men had become essential to the colonies’ liberal and radically democratic credo — amounting to a demand that even the sovereign be held accountable under the law. The economic underpinnings of Quesnay’s idea were still there, but they had become somewhat subsidiary to the notion of civil liberties. The French Physiocrats, whose philosophy Quesnay helped to define, largely rallied to the American cause; one of them, Éleuthère Irénée du Pont de Nemours, transplanted himself to Delaware to pursue his business interests and his ideas, founding what would become an American chemicals giant. Still, although these thinkers were driven by a classically liberal political premises, they managed to reconcile themselves with ease to the French monarchy. With time, however, some came to embrace the French Revolution, just as they had taken up the American.

It is a common misconception, though one that abounds in American politics, that laissez-faire capitalism supposes less law and less regulation. In fact, it supposes a legal regime that advances the interests of the entrepreneurial class, which at length is what evolved in America. The Physiocrats advanced an even more vigorous posture regarding laws and their enforcement: “The supreme being wants man to be free; but this liberty is viewed from varying perspectives under which man might preserve order or otherwise be thrown into a state of disorder,” Quesnay wrote. “This supposes the need for precise laws defining precisely his duties before God, towards himself, towards others… perspectives in which politics and religion are brought together to define a natural order which they must follow.” Hence, Quesnay wrote, an intelligent observer would not seek deregulation, which would lead to destructive chaos, but rather regulations that coincide with laissez-faire economic principles — namely regulations that promote the rights and protect the property of the entrepreneur.

This position sounds inherently contradictory, and perhaps it is, but it has been borne by the free-market movement to the present day. America has witnessed a resurgence of laissez-faire arguments over the past fifty years, as the Chicago School has cruised to dominance in the nation’s law and business faculties, and has come to control discussion of basic policy issues. It is therefore no surprise that this same period has witnessed a dramatic explosion in the nation’s prison population, a harshness in sentencing unequalled among Western nations, and the increased privatization of the criminal-justice process. Indeed, the administration of laws has emerged as simply another business and another source of profit. Somewhere along the way, the fundamental notion of justice has faded both in importance and in meaning.

As Bernard Harcourt has persuasively argued, the germ of this immense problem can be found in the early works of the Physiocrats, who provided much of the foundation upon which Milton Friedman and his followers constructed their school. Both movements, it seems, have led to considerable skillful and innovative thought. But as Voltaire wrote in two critical letters, the basic philosophy contains an admixture of error, even as it has been pursued with a boundless enthusiasm and an intellectual arrogance that should not be mistaken for true science.

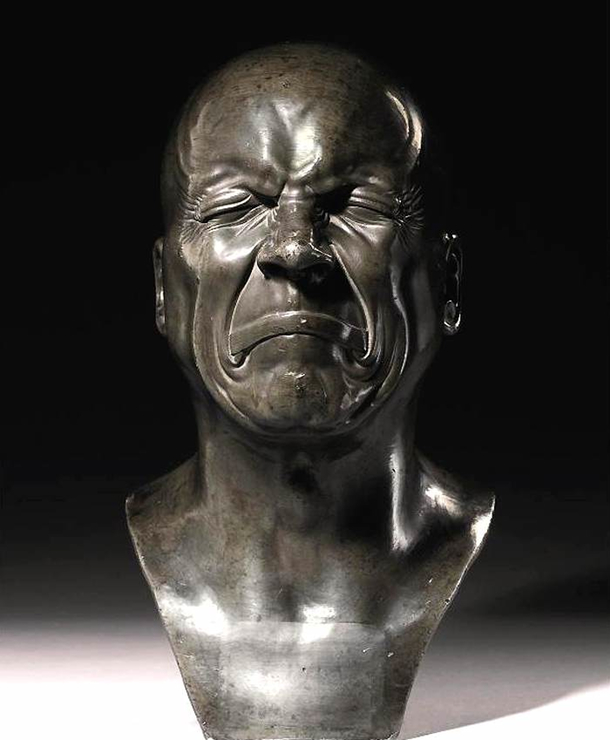

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt was a Bavarian sculptor of the neoclassical period. Much of his work focused on physiognomy, the notion that outward facial expressions can reveal the inner spiritual state of their subject. His work is the subject of a recent major exhibition mounted jointly by New York’s Neue Galerie and the Louvre in Paris. His work is discussed by Willibald Sauerländer in a marvelous New York Review of Books essay from October 2010, entitled “It’s All in the Head.”

The notion that the force of nature caused chaos to give way to reason and order was essential to the early Enlightenment. Listen to an unusual orchestral presentation of this concept in the opening (“Chaos”) of Jean-Féry Rebel’s ballet Les élémens (1737). A series of dissonant chords, unheard of in his time, dissolves into harmonies, then is followed by a presentation of the elements. The performance is by Reinhard Goebel and Musica Antiqua Köln: