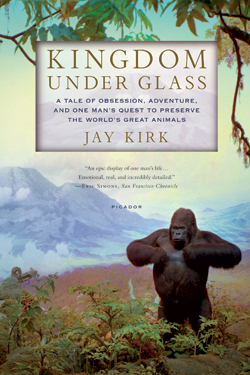

Kingdom Under Glass, by frequent Harper’s Magazine contributor Jay Kirk, came out in paperback in late November. The book tells the story of the remarkable career of Carl Akeley, the taxidermist who in 1909 dreamed up the African Wing of the American Museum of Natural History. Along the way, Kirk creates a kind of cyclorama of the early twentieth century: eugenicist museum curators; Teddy Roosevelt on safari; “Kodak King” George Eastman baking huckleberry pies in Kenya; and the forty-six-pound heart of P.T. Barnum’s Jumbo, preserved in alcohol. Harper’s asked Kirk six questions about the boundary between history and fiction, navigating racism in primary sources, and Akeley’s artistic legacy.

1. You first stumbled across Akeley while writing a story for Harper’s. What made you identify him as a subject for a book?

The Harper’s piece was about the non-existence of the Eastern Panther (Puma concolor couguar). I’d been reading a lot of natural history to understand how it had gone extinct in the nineteenth century before making a return as Bigfoot’s feline cousin, and I came across something in passing about a “famous taxidermist” who had once strangled a leopard with his bare hands. When I realized this was the guy behind the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History, I immediately became intrigued. I grew even more so when I learned of his obsession with being a True Artist, and how, in order to fulfill that obsession, he had not only strangled a leopard, but gone on these insane, massive expeditions, dragging with him small armies of painters and sculptors, and terrorizing his African porters along the way. I think what I found so compelling was the idea of anyone going to such preposterous lengths for something that, in the end, as art—or even as the “scientific” contribution it purported to be—was dubious at best. I also liked having a story where I could meditate on the absurdity of adventure in general—for me, it kind of throws a cheery light on the pointlessness of all human ambition. Most appealing, though, was the paradox of Akeley’s character: he killed animals in order to save them.

2. Reviewers have praised the “novelistic” feel of the book. It pivots easily from pointillist historical detail to vivid, emotionally colored narration. How did you come by this voice?

To a degree, my method was to imitate Akeley’s own. Taxidermy and narrative nonfiction share a lot in common, so it wasn’t such a big leap. They can both leave you feeling a little morbid—all this flensing and bloodletting just to bring something back to “life.” Akeley’s dioramas are hypermimetic little scenes that he brought off in part by making countless measurements and sketches of each unlucky subject before slapping on the first glob of clay. I think his mania for verisimilitude makes the dioramas feel hypnotic and yet simultaneously a bit too literal.

I wanted to be literal, but only to a point. The book was meant to be rigorous nonfiction, with enough endnotes to assure even the most skeptical reader of the veracity of any given detail or fact—but in order to get the tone I was after (non-facty, “novelistic”), I had to first do the work of a biographer, and then, I suppose, to kill the biographer. I say kill the biographer not because I dislike biographers, but as mental shorthand for the way I reminded myself that while I was obligated to the facts, I was under no obligation to be comprehensive. A more responsible biographer would probably have dedicated at least half a chapter to Akeley’s inventions—to his design for bullet-proof spotlights, his numerous patents for dentistry equipment, his cement gun (which you can read about on Wikipedia, if you’re really interested). My primary obligation was to story. Unlike a biographer, I was free to come and go—and so, I considered the biographer killed. Which, come to think of it, would make a nice start for a diorama: the biographer, embalmed in his natural habitat, the archival vault, wearing a pair of twee, lint-free cotton gloves, maybe with a vulture perched nearby on a library cart.

3. You spent five years researching this book. How difficult was it to structure all the information you dug up? Was there anything you were particularly sorry to leave out?

Putting it all together was less like taxidermy than making a claymation feature, or maybe one of those six-hour Italian features, minus the Italian actors. (Unless you count the cameo I included of General Oreste Baratieri, who was ejected by the Eritrean warlord Emperor Menelik II during Italy’s failed bid for a slice of the African cake. If you were really doing claymation, it would take a year just to position all the dead Italian soldiers—4,133 of them, to be exact.) Whereas Akeley would shoot an elephant, then spend three years up a ladder slapping clay onto the manikin, tediously following his gazillion sketches and measurements, the writing of my book, while mostly fun, often felt like a slow game of arranging clumps of factoids and weird details that I had collected on my own long safaris in the library. Just a lot of arranging. That word is very useful when you’re talking about the art of nonfiction.

As for what got left on the cutting-room floor, for the most part, I was happy to leave out what I did: a hundred or so elephant hunts that went nowhere. I do regret cutting a chapter about Akeley’s apprentice, Robert Rockwell, who went on to complete many of Akeley’s dioramas after he died. Rockwell was working at the Brooklyn Museum right before World War I broke out, and this crazy thing happened while he was doing some spring cleaning. His assistants had removed the large pane of glass in front of the American Bald Eagle diorama, to let Rockwell get inside with his nozzle-jar of carbon disulfide, which is this very unstable, flammable stuff. He fumigated the nest (which was enormous and weighed something like one ton, if I remember correctly), but no sooner had he finished and turned to leave than he heard a massive explosion. When he looked back, two of his assistants were unconscious on the floor, lying in pools of blood, while the third had been speared through the chest with a long shard of glass, dead. I kind of loved that image of the glass and bits of blown-up nest scattered across the room—and amid all the smoking carnage, the bald eagles crumbling in flame. I wanted to use it as my entry into the World War I section, but for some reason we chopped it.

From Kingdom Under Glass:

It was in Milwaukee where Carl would first discover the cyclorama. Created by German émigré artists fleeing the potato blight and the iron fist of King Frederick William III—only now to endure the iron fist of Frederick Pabst—these monster illusions dotted the city. As tall as fifty feet and as long as a football field, the cycloramas were huge paintings that engulfed the viewer in the center of a Civil War battle, the crucifixion of Christ, or panoramic scenes of ancient Rome in flame, overrun by barbarian Ostrogoths. The canvas screens revolved around the viewer on a series of mechanical rollers, giving the audience the mesmerizing, if slow and squeaking, impression of what some had come to call moving pictures, a term Edison hadn’t yet appropriated. The elaborate attention to detail, the lighting, the smell of pigment, the grand scale of it all lulled in the taxidermist’s hungry imagination. He too wanted to make something that would conquer an audience this way, a suspension of disbelief.

Nearly as mesmerizing was what he encountered at the dime museum on Grand Avenue. There Akeley and Wheeler saw the same sort of sensationalist wonders to which Barnum was treating the world: shrunken heads, fake mermaids, and erotic tableaux of young girls in flesh-colored tights posing as nude paintings. They would also come across the live savage exhibit, which no doubt gave their talks about Rousseau a certain new urgent slant. Carl had never come face-to-face with an actual aboriginal before. At the dime museum, the savage’s station was by the front entrance, near a giant mud anthill, inside of which visitors were presumably led to believe the native ate and slept after museum hours. Etched with war paint, dressed in a barkcloth robe, and dandling a whale-bone spear, this lone ambassador from some far-flung primitive nation stared out from behind a glass partition with tired eyes. A label on the wall by the exhibit revealed that he was from a tribe called “Earthmen.”

4. The book’s endnotes are fascinating, not just as bibliographical appendages, but as narratives of the research process. For instance, you note, regarding a scene in which you describe Akeley and his wife wearing dust goggles while riding the Uganda Railroad, that you were using “inference to develop scenes without crossing the boundary into fiction.” How do you know when you’ve crossed that boundary?

I worked with Francis Bacon’s dictum about historians needing to impose “weights on the imagination, not wings” throughout, though I also felt going in that nonfiction is burdened by too many false and unnecessary restrictions, or the wrong kind of restrictions. I tried to signal that with my epigraph, from the historian Eric Foner: “Works of history are first and foremost acts of the imagination.” Using the example of the train ride, neither Carl nor Mickie ever mentioned the dust goggles I describe them as wearing on the train, nor did I ever see a photograph of them in said goggles. However, from Charles Miller’s exhaustive Lunatic Express: An Entertainment in Imperialism, a history of the Uganda Railroad and the settlement of British East Africa, I learned that in addition to all the other discomforts of the train ride (ceaseless thirst, bad food) “dark goggles were also advised… as protection against the desert’s red dust which penetrated every compartment in billowing red clouds.” Of course, that doesn’t prove the Akeleys wore those goggles, but they were sensible, well-equipped travelers, and I was comfortable enough with the probability that they had worn them to omit the milksop subjunctives such as “in all likelihood the Akeleys were also wearing those goggles” or “it very well may have been that the Akeleys could be found thus goggled.”

5. Your safari narratives depend heavily on first-hand accounts written by Akeley, his wives, and other members of his expeditions, nearly all of whom communicate attitudes toward Africa and race that we find appalling today. To what extent can we trust their descriptions of porters and other Africans?

We can’t. There is absolutely nothing trustworthy about the portrayal of the Africans encountered by the white characters in my book. The Africans who get even a semblance of personality are clearly nothing but distortions of my characters’ points of view. I don’t even know if they have enough dimensions to register as caricature. They are background, stage furniture—except of course they’re actually carrying the furniture the white characters sit on after a long day of marching over the veldt.

And yet, the whole book is kind of an essay on race. The safaris were only an extension of the madness of the museum’s scientific agenda. The primary purpose of the safaris was to collect (that is, kill) these creatures, to create time capsules of the doomed so that the educated people of the future would be able to see what had been lost in the name of progress. But ironically, the American Museum of Natural History was complicit in this progress: it’s no coincidence that it was building new halls during an era in which American interests were expanding overseas. The museum had initially filled up with specimens (not to mention ethnological curios from exterminated native tribes) from the expanding Western frontier. Then, as the United States sought new markets worldwide and became more of an imperial contender, the museum had built halls to accommodate artifacts from newly explored corners of the globe. During Teddy Roosevelt’s second term alone, the museum sent expeditions to the East Indies, the Arctic Ocean, Alaska, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Tahiti, the Philippines, Samoa, Trinidad, Venezuela, Egypt, and Hawaii. Akeley’s boss, Henry Fairfield Osborn, the president of the museum, often referred to his acquisitions as “conquests.”

Osborn was also a leading, outspoken eugenicist who believed that the discreet and neat divisions between species that his dioramas demonstrated could serve as a moral lesson to the immigrants crowding the Lower East Side, whom he (along with a lot of his fellow aristocrats) feared would violate Nature by committing the noxious act of miscegenation and commingling their defective “race plasm” with his own Nordic stock. “Put three races together,” he liked to say, “and you are as likely to unite the vices as the virtues.” He actually hosted at least one major international eugenics conference in the twenties at the AMNH. He was a big fan of Hitler.

6. The book argues convincingly that Carl Akeley really was an artist, a man with a calling—not just for taxidermy, but sculpture as well, as evinced by his bronze self-portrait, Chrysalis, which depicts “the artist pushing the skin of an ape down around his hips.” Is his legacy as an artist tainted by the fact that he had to kill in order to preserve?

Probably no more or less than Norman Mailer’s reputation was tainted by his attempt to kill his wife. And in fact, Akeley’s wife claimed that her husband once tied her to the bed and turned on the gas. (The only other witness, unfortunately, was her mentally unstable pet monkey, J.T. Jr., so we’ll probably never know the whole truth.) On no count is Carl an entirely sympathetic character. One does have to grant him the victory, however, of having saved the mountain gorilla. If it weren’t for his efforts to persuade the Belgian government to create Africa’s first wildlife sanctuary, in the Virunga mountains, that species would without question have vanished. Dian Fossey wouldn’t have had anything left to protect.

As for Akeley’s legacy as an artist, one need only look at the work of Damien Hirst or Walton Ford to appreciate his influence. And now, Akeley seems to be gaining a new audience with the emergence of what can only be called Dadaist taxidermy. I’m thinking in particular of the Minnesota Association of Rogue Taxidermists who make hybrid creations using parts of a dead pig and a stuffed teddy bear, say, or in one instance turned a kneeling fawn into a fur-upholstered ice-cube tray. I like these departures from realism. I mean, if you’re playing with dead animals, why not fuck around and innovate? I’m starting to feel the same way about nonfiction. Historically, it took a long time for taxidermy to part ways with realism. Why is nonfiction still stuck? And don’t say it’s because nonfiction deals with reality, because, as we all know, reality must include even that rarefied imaginary space wherein some guy out in Minnesota is dreaming about stitching a pig’s face to a trashpicked Winnie the Pooh. I, for one, may take my next cue from these experimental necrophiles.