Michael Hastings’s Polk Award–winning Rolling Stone article, “The Runaway General,” brought the career of General Stanley McChrystal, America’s commander in Afghanistan, to an abrupt end. Now Hastings has developed the material from that article, and the storm that broke in its wake, into an equally explosive book, The Operators, which includes a merciless examination of relations between major media and the American military establishment. I put six questions to Hastings about his book and his experiences as a war correspondent in Iraq and Afghanistan:

1. Your book presents a Barack Obama who behaves uncomfortably and perhaps too deferentially around his generals, but who is also the first president since Harry S. Truman to have sacked a theater commander during wartime—and moreover, who did it twice (first, General David McKiernan, then McChrystal). How do you reconcile these observations?

I actually think the two observations reveal an evolution in the president’s relationship to the military. During my reporting, one of the conclusions I came to was that President Obama’s mistake wasn’t firing General McChrystal—it was hiring him in the first place. General McKiernan wouldn’t have been a political headache for the president; McKiernan wouldn’t have waged a media campaign to undermine the White House, nor have demanded 130,000 troops.

The president didn’t come up with the idea to fire McKiernan on his own. He was convinced to do so by Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Admiral David Mullen, and General David Petraeus. He took their advice without questioning it, really. That, I believe, was his original sin in dealing with the military. The rap on McKiernan was that he was a loser who just didn’t get it. I never bought that narrative—nor did a number of military officials I spoke to. McKiernan understood perfectly well what counterinsurgency was, and he’d started enacting it. (There were fewer civilian deaths under McKiernan than McChrystal.) But McKiernan was on the wrong team—he was the victim, essentially, of bureaucratic infighting. At the time, the president had put a lot of trust in Gates and Mullen (misplaced, in my opinion) and didn’t have the confidence to say, “Hey, wait a second, maybe McKiernan should stay.”

Then, a few months after McKiernan was fired, McChrystal set off the infamous strategic review. McChrystal publicly criticized the vice president, leaked that he was going to resign, and had his allies in the media ratchet up the pressure to escalate. The president felt boxed in, or jammed. He wasn’t comfortable enough at the time to truly stand up to the military. They never gave him the plan he asked for—instead, they gave him the plan he explicitly said he didn’t want, a plan that required a decade-long nation-building commitment. He vowed that he would never get jammed again, according to my White House sources. And, I think, the firing of McChrystal was, in part, the White House sending a very strong message—i.e., I might have been a bit wobbly at first, but I’m your commander-in-chief.

2. It seems ironic that McChrystal got a pass over the Pat Tillman affair and the prisoner-abuse scandal surrounding Camp Nama, but then was sacked over the publication of your article, which revealed informal sarcastic banter involving him and his staff of a type that would surprise no one who has dipped into a war command environment. Does this tell you anything about the political environment in Washington? Was Obama’s decision correct?

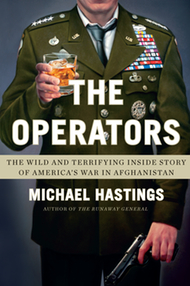

My editor, Eric Bates, had warned me about falling into the access trap. By becoming so indebted to them for the access they’d given me, I’d lose my objectivity… I could already start to feel the pull. I was starting to like them, and they seemed to like me. They were cool. They had a reckless, who-gives-a-fuck attitude. I was getting inside the bubble—an imaginary barrier that popped up around the inner sanctums of the most powerful institutions to keep reality at bay. I’d seen the bubble in White Houses, on the campaign trail, inside embassies, at the highest levels of large corporations. The bubble had a reality-distorting effect on those inside it, while perversely convincing those within the bubble that their view of reality was the absolute truth. (“Establishment reporters undoubtedly know a lot of things I don’t,” legendary outsider journalist I.F. Stone once observed. “But a lot of what they know isn’t true.”) The bubble compensated for its false impressions by giving bubble dwellers feelings of prestige from their proximity to power. The bubble was incredibly seductive, the ultimate expression of insiderness. If I succumbed to the logic of the bubble, I could lose the desire to write with a critical eye.—From The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan. Reprinted by permission of Penguin Group (USA). © 2012 Michael Hastings.

I’ve never really had a strong opinion on whether McChrystal should have been fired. My most stinging criticisms have always been aimed at policy, really. But the fact that it was making fun of Vice President Joe Biden and Ambassador Richard Holbrooke that ended his military career—rather than him being involved in a high-profile cover-up, or in one of the more shameful episodes in the Iraq War, or in pushing a doomed strategy that won’t make us safer—says a lot about (a) the priorities of the Beltway political and media class, and (b) how angry the White House had been about the Pentagon’s behavior. At the same time, I think the fact that McChrystal got away with both of the things you mention—essentially operating outside the law for the previous decade, in this shadowy and very dark world we still know very little about—played into this idea that he was untouchable. That he could say anything he wanted and do anything he wanted. If you can get away with such audacious behavior, what’s trashing the VP? Not even on the same scale of risk, or apparent danger.

What I’m saying is: cover-ups, torture camps, and a culture of complete impunity are intimately linked to the kind of reckless contempt Team McChrystal displayed for the civilians in Washington.

As an aside: If I was applying for a job, and I were asked the question, “How many cover-ups of the deaths of national heroes have you been involved in,” and my answer was, “Well, just one,” I wouldn’t get the job. None of us would get the job—we’d be in jail!

3. Your article triggered two internal probes by the U.S. military that—like the recent probe into David Barstow’s Pulitzer Prize–winning story on the Pentagon’s manipulation of ostensibly independent military experts who appeared on broadcast news—exonerated the Department of Defense and questioned the accuracy of the reporting. What do you make of these internal investigations?

Is whitewash one or two words? In my experience, when the DoD investigates itself—especially when powerful people are involved—they find they did nothing wrong. Or, they find some low-level asshole to hang out to dry. The multiple Pentagon investigations into the Rolling Stone story were particularly absurd. First, the Army investigated and found that it was the Navy’s fault. Then, the Pentagon Inspector General’s office took over and found that it was Rolling Stone’s fault. They spent nine months on the investigation to find out “what happened,” when all they had to do was read a copy of the magazine. Of course, the results of these investigations were invariably reported with pro-Pentagon spin. Thom Shanker, the New York Times’s Pentagon correspondent, didn’t even bother calling us for comment before he ran with the Pentagon spokesperson’s story “clearing” McChrystal, whatever that meant. (I refer you to the statement Obama made when he fired McChrystal—that’s why he got fired, not because he explicitly broke any laws. The Pentagon’s attempt at rewriting this history has been disturbing to observe.)

I suggest reading the report of the investigations in full, if you want some comic relief. It suggests that a few scenes in my Rolling Stone story were taken out of context. What is the proper context, I wonder, for saying the French minister is “fucking gay”? For flicking the middle finger to your commanding officer? For getting shit-faced and stumbling in the streets? We provided plenty of context in the article, and the book lays out some of these incredible scenes in much more detail.

I think the only way to have actual accountability is for Congress to fulfill their oversight role, but even that’s not foolproof.

4. Your book pays at least as much attention to the Pentagon press corps and its relationship with power as it does to Stanley McChrystal and his team, and you write that after your article ran, you found that you had few problems dealing with military and political figures, but your relations with many of your fellow journalists had been poisoned. Why?

McChrystal was a spokesperson at the Pentagon during the invasion of Iraq in March of 2003, his first national exposure to the public.

“We co-opted the media on that one,” he said. “You could see it coming. There were a lot of us who didn’t think Iraq was a good idea.”

Co-opted the media. I almost laughed. Even the military’s former Pentagon spokesperson realized—at the time, no less—how massively they were manipulating the press. The ex-White House spokesperson, Scott McClellan, had said the same thing: The press had been “complicit enablers” before the Iraq invasion, failing in their “watchdog role, focusing less on truth and accuracy and more on whether the campaign [to sell the war] was succeeding.”—From The Operators: The Wild and Terrifying Inside Story of America’s War in Afghanistan. Reprinted by permission of Penguin Group (USA). © 2012 Michael Hastings.

The original article contained an implicit criticism of a few of my colleagues, so I guess I shouldn’t have been so surprised by the backlash. They would have ignored the implicit criticisms if they could have, but the story garnered too much attention. All of a sudden Jon Stewart is on the Daily Show saying, “Hey, you other guys suck.” I think that embarrassed a number of folks who weren’t used to being embarrassed. They are accustomed to being the unquestioned journalistic authorities of these wars. And, as a general rule, war correspondents are a competitive and catty breed. Put ten war reporters at a dinner table and one of them leaves the room, seven others at the table will tell you the guy is a dick, she misbehaves with sources, he’s a sketchy womanizer, he can’t be trusted, he makes stuff up, she doesn’t deserve this or that. Usually—it’s such a small, tight-knit community—that kind of dirty laundry is kept secret among the “luckless tribe,” as one reporter once described us. That’s the micro level.

On the macro level, there was something much larger than myself, or Rolling Stone, or McChrystal. It had to do with how the media, as a whole, had been covering these wars. And despite the best efforts of a number of excellent journalists, on stories from WMDs to the escalation in Afghanistan, we’ve done a pretty spotty job, I think. I also came to consider the Pentagon press corps not as a watchdog of the Pentagon, but an extension of the Pentagon. This was a critical insight for me.

5. Through 2007 and 2008, Iraq War reportage was heavily dominated by a narrative saying “the surge is working.” In retrospect, was the focus on the right issue? What does this line tell you about the media–military relationship?

Hah, yes, the surge is working. (As the latest news from Iraq shows—another sixty dead in a bombing…) In some ways, though, it wasn’t totally inaccurate. Eventually, after we unleashed a tremendous amount of violence in 2007 and 2008, violence decreased. But I would refer you to what a young officer named Major David Petraeus wrote in 1987—that it isn’t what happens on the ground that matters; it’s the “perception” of what happens that is key.

Remember, though, there was never really a time during the Iraq War that the military didn’t say that what they were doing was working. The same thing goes (except for the brief moment when McChrystal took over) for Afghanistan. But all we have to do is look to Iraq to see what “working” really meant: a face-saving withdrawal that Petraeus could spin as a victory, in my opinion. Petraeus had a receptive audience in Washington for the line—so many top policy makers and journalists had been complicit in starting the war in Iraq. What incentive did they have to question the victory narrative that Petraeus was handing to them?

6. Last week, the Pentagon released its latest defense strategic review, which guides defense spending for the fiscal years 2013 to 2018. Counterinsurgency (COIN) has fallen to ninth place among the nation’s military missions, outstripped by things like cybersecurity and support for domestic police operations. Given what you observed in Iraq and Afghanistan, is this a good thing?

Two years ago, I spent another Christmas holiday season in Baghdad, one of probably three I spent over there. And one of my journalist colleagues looked around the dinner table and said, “If you’re having Christmas in Baghdad, you’ve already lost.”

So yes—the demise of COIN is a victory for competence and decency. It’s also a slap in the face to all these experts who’ve been riding the gravy train for the past ten years, pushing a strategy that was (a) extremely expensive, (b) extremely deadly, and (c) would not, and did not, make us safer. Good riddance to COIN. Let’s hope it doesn’t come back.