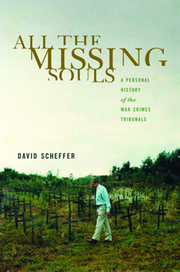

Ambassador David Scheffer steered America’s engagement with the concept of war-crimes accountability throughout the Clinton years, and has been one of the nation’s leading observers and commentators on the subject since then. He has now published a major work, All the Missing Souls: A Personal History of the War Crimes Tribunals, that chronicles America’s pursuit of war criminals during the Nineties and offers clear insights into the issues these efforts raised for future generations. I put six questions to Scheffer about his book:

1. In the Wall Street Journal, torture-memo author John Yoo argues that you “fail to understand” that the humanitarian challenges of our age demand the robust use of military force, and that international tribunals “will do little to stop the killing.” As a defendant in pending litigation in Spain, Yoo has pressing personal reasons to oppose the concept of universal jurisdiction, but aside from that, how do you respond to his critique?

If John Yoo had bothered to check the record, he would have found that I have been an advocate of humanitarian intervention and the “responsibility to protect” principle, both of which contemplate the utility of using military force to protect civilian populations from atrocity crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes). During the Balkan conflict, Ambassador Madeleine Albright and I repeatedly sought more effective use of air power, and I personally sought the introduction of U.S. troops years before the Dayton Accords. The Clinton Administration’s use of air power over Kosovo and Serbia, followed by the introduction of NATO troops into Kosovo in June 1999, was no small measure of commitment to the utility of military force. So I really do not need Yoo’s counsel on the utility of military force to stop the killing. The fact that such intervention did not occur during the Rwandan genocide of 1994 was a terrible mistake. But had I resigned at that time, as Yoo advocates, I would have been unable to help address situations in the field and in the newly created tribunals drawing upon the lessons of 1994.

Yoo is also employing a straw man to denigrate international justice. The primary purpose of the international criminal tribunals is to render justice and reveal some of the truth of what transpired. That means investigating massive crimes and leadership suspects, indicting and prosecuting some of them, and rendering judgment followed by either conviction or acquittal. It is a false burden to place on the shoulders of the tribunals to assess their legitimacy and utility by whether they “stop the killing” or deter further atrocity crimes. Such deterrence is a tremendous bonus if it occurs, and we hope for it, but that is not the purpose of the tribunals. Victims want top perpetrators to suffer punishment and that is precisely what criminal courts are designed to achieve, particularly when there are hundreds of thousands of victims and those responsible for such horrors grasp the levers of power.

Nonetheless, international tribunals have had a generational impact on war-ravaged societies. Professor Kathryn Sikkink, in her new book, The Justice Cascade, uses comparative empirical research over the last three decades to demonstrate how human-rights prosecutions at the domestic and international level in fact have led to a decline in human rights abuses and atrocity crimes in the relevant nations and even in neighboring countries over the long term. I believe we will see similar results in the Balkans, several regions of Africa, and Cambodia in decades to come.

It is also very important to ask whether, in the absence of tribunals and indictments, tyrants and atrocity lords are coming to the peace table and negotiating settlements to stop the killing. Does that empirical evidence stand up to scrutiny any better than the many examples of the past two decades where leaders under investigation or indictment lost their domestic and international legitimacy and ultimately their power? Consider the ultimate fates of Slobodan Miloševi?, Jean Kambanda, Charles Taylor, Radovan Karadži?, Ratko Mladi?, Muammar Qaddafi, and even President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan.

In the final analysis, we need both tools—international justice and military force—to confront most effectively the challenges of atrocity crimes. How we use each tool and under what circumstances is the challenge of wise policy-making far removed from the knee-jerk resorting to go-it-alone U.S. firepower advocated by Yoo.

2. The United States has of course made heavy use of the universal-jurisdiction concept in going after foreign war criminals like “Chuckie” Taylor of Liberia, and a number of European nations like Spain, Italy, Belgium, and Germany have done so as well, occasionally to the irritation of the United States. What role remains for national courts exercising universal jurisdiction, as distinguished from the International Criminal Court (ICC)? Should national courts continue to be the first recourse for such matters?

The United States does not escape scrutiny as a country invoking the spirit of universal jurisdiction in its domestic laws. Several judges of the International Court of Justice opined in 2002 that we should examine obligatory territorial jurisdiction in national courts for acts committed elsewhere. U.S. courts for years have been widening various categories of jurisdiction in combating international drug trafficking, international terrorism, securities regulation, and atrocity crimes, including torture. Three recent laws demonstrate the trend, one based on a simple premise: the United States will no longer be a sanctuary for perpetrators of atrocity crimes overseas. Laws on genocide, child-soldier recruitment and use, and human-trafficking accountability have been enacted since 2007. These laws are near-universal-jurisdiction laws, just like the Torture Act that brought “Chuckie” Taylor to justice in a Florida federal court. They criminalize the commission of such crimes by anyone anywhere in the world, but trigger U.S. jurisdiction only if the perpetrator, including one classified as an alien, sets foot on U.S. soil. That is an enormous leap for federal courts, and an entirely logical one that attracted broad bipartisan support for each law. The United States must not be a sanctuary for such perpetrators.

The ICC encourages national courts to exercise jurisdiction over atrocity crimes and their perpetrators if such courts have personal jurisdiction over the perpetrators. Deferral to national courts is labeled complementarity; it is a very active principle in the work of the ICC. A nation must demonstrate its political willingness and judicial capability to investigate and, if merited, prosecute atrocity crimes of interest to the ICC in order to avoid its scrutiny. That dynamic, between national courts and the ICC under the principle of complementarity, is nearly the whole ball game and speaks volumes to the interactive character of international justice today as it weaves its way forward between international and national courts.

But it would be a mistake to conclude that national courts automatically are the first recourse for such matters. When building the international criminal tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and the Special Court for Sierra Leone in the 1990s, we were confronted with devastated domestic legal systems that would take many years to rebuild. The court of first resort under those circumstances might well be an international tribunal. There is a debate over whether, when the U.N. Security Council refers an atrocity situation to the ICC under the U.N. Charter’s Chapter VII mandatory enforcement power (as it did on Darfur in 2005 and Libya in 2011), complementarity should be employed at all or whether the prosecutor should launch into investigations without waiting for a domestic buy-in to render justice. After all, the Security Council deemed it necessary to refer the situation to the ICC in part because no domestic legal system has functioned to the date of referral to render justice for the commission of atrocity crimes.

3. You provide a vivid description of your journey to a snowbound New York on December 31, 2000, to sign the Rome Statute of the ICC, and of the vindictive steps taken against you almost immediately thereafter by Republican opponents of the court. Looking forward now a little more than a decade, how do you see interests arrayed in Washington on the ICC question? Has the manner in which the Bush Administration conducted the “war on terror” made it more difficult for Washington to participate?

Ever since 2005, when the Bush Administration abstained in the U.N. Security Council referral of the Darfur situation to the ICC, the tide has turned in Washington toward greater cooperation with the Court as well as greater appreciation of its utility in advancing both international justice and U.S. interests. It only makes sense, as so many American interests are advanced in the work of the ICC. The Obama Administration has intensified the cooperative linkages. These include sending a sizable U.S. delegation to observe the meetings of the Assembly of States Parties (which now number 120 nations, including all U.S. allies other than Turkey and Israel) and participate in their discussions, including on the crime of aggression. President Obama deployed 100 U.S. military trainers to Uganda in October 2011 to assist that country’s armed forces in tracking, apprehending, and transferring to The Hague to stand trial four top indicted fugitives of the Lord’s Resistance Army. The U.S. Congress long ago repealed the punitive measures of the American Service-Members’ Protection Act as illogically undermining core U.S. interests. So there is progress in Washington, and the United States can do much to advance the work of the International Criminal Court without becoming a state party at this time. That being said, a formidable body of opinion in Washington remains intimidated by the prospect of international justice and opposed to robust American participation in that quest. In my book I counter that point of view, as well as the crutch of American “exceptionalism” that some employ to avoid participation.

I would argue that the manner in which the Bush Administration conducted the so-called “war on terror” makes it even more imperative now for the United States to re-engage on the side of international justice and not seek ways to avoid it or leave to others the leadership required in an increasingly complex and challenging world. We need to remind ourselves that the individuals being brought to justice before the international criminal tribunals with due process protections are often responsible for far more death and destruction than the individuals sitting in Guantánamo. The international tribunal defendants have been brought to justice or are being currently prosecuted under secure conditions before civilian judges, and most are being convicted and sentenced.

The Obama Administration has significantly cleaned up the Military Commissions in Guantánamo, and also sought to use civilian federal courts but was repelled by Congressional opposition. There is no question that the Bush Administration’s record tarnished the American brand in international justice and made it a more difficult task to re-engage with other governments for the purpose of advancing U.S. interests. But a start has been made under President Obama’s leadership.

4. Notwithstanding its internally conflicted status as a non-participating architect of the ICC, Washington today appears eager to make regular use of the ICC as a foreign policy tool. We see this in dealings surrounding Darfur, Kenya, Libya, and now Syria. How can these contradictory positions be reconciled?

It remains an awkward position for the United States to occupy. We should not be surprised that there are charges of hypocrisy when foreign governments witness our diplomatic efforts to impose upon these African nations the scrutiny of the ICC and yet the United States refuses to join the Court. One of the fundamental means to reconcile this contradiction—short of ratifying the Rome Statute of the ICC—is to ensure that the Justice Department, the federal courts, and the U.S. military justice system are fulfilling at all times their own duty to hold Americans accountable, under U.S. law, for the commission of atrocity crimes. If we can demonstrate at home that we are prepared to fully investigate and prosecute the perpetrators of torture, war crimes, and other heinous international crimes, the United States can exercise precisely the kind of complementarity to domestic courts so strongly mandated by the Rome Statute. The United States can become a de facto member of the ICC by supporting its important work with our unique capabilities and influence in the Security Council while honoring the core principle of investigating and prosecuting our own in U.S. courts.

Yet the U.S. legal system has fallen far short of credible justice with respect to the so-called “war on terror” and the full range of U.S. military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade. The Haditha (Iraq) military rulings of recent date only amplify a profound problem we have in facing up to these crimes at both the leadership and subordinate levels. There is a clear need to modernize both the U.S. federal criminal code and the Uniform Code of Military Justice to align both prosecutorial tools with the international tribunals’ significant work in updating what should be prosecuted and how.

5. In sub-Saharan Africa, the ICC is sometimes ridiculed as the “ICC for Africa,” while other special tribunals are lampooned as curiously colonial in nature and staffing. The hybrid West Africa court seems geared to take these criticisms on. Do you see them as the way of the future?

The hybrid courts are one means of adjudicating a multi-dimensional challenge of international justice. They are by no means the full answer, for they can lack the resources, skills, political will, and experience to address some of the toughest challenges of justice now and in the future. One of the key rationales operating in the creation of the ICC during the 1990s was to build a court that could operate with relative efficiency in administering international justice, rather than undertake the costly and much delayed procedure of building ad hoc tribunals for every atrocity situation that arises. Regional hybrid courts of permanent status that are, in effect, mini-ICCs, can make sense provided there is prolonged commitment by regional nations to fund and sustain such courts with requisite expertise over the long term.

6. In Spain today, Judge Baltasar Garzón, who is best known for his path-breaking work in the area of universal jurisdiction in cases like the Pinochet prosecution, stands accused of exceeding his authority by opening an investigation into mass killings of the Franco era. He plainly disregarded immunity granted to Francoists when the transfer of power from Franco-era to modern Spain occurred. Garzón argues, with the support of a number of Latin American jurists and bar associations, that there can be no effective immunity granted for crimes against humanity. This seems to be a recurring issue around the world—national legislation granting immunity to war criminals is challenged by proponents of the international-law view that certain crimes are so heinous that no immunity can be recognized. How do you expect this struggle to unfold?

At the domestic level, to defeat immunity deals of the past (particularly those enacted into law by the leadership perpetrators as they cede their own power) we need to engage constitutional scrutiny. The immunity arrangement may fail key tests, particularly when political leaders press for self-examination. Nations embrace international legal obligations through treaty law and customary law. If a domestic immunity law conflicts with that international legal obligation, national courts increasingly have invalidated the domestic law. This has occurred in Latin America in recent years. Perhaps one day it will be Spain’s turn to subject its own immunity law to rigorous constitutional scrutiny under enlightened leadership in Madrid. As for the United States, the immunity provision built into the Military Commissions Act of 2006 is shameful and requires soul-searching by a nation dedicated to the rule of law.

Internationally, there is an emerging consensus that international organizations and tribunals will not countenance domestic immunity laws or agreements in the work of the international tribunals regarding political and military leaders. It is simply implausible today, when 120 nations are party to the ICC and international justice is a daily theme of work in the United Nations and in the European Union, for example, for diplomats to casually sit down and embrace a domestic immunity deal for leaders as if it were some benign feature of international politics. That bridge has been crossed in the past two decades and will not be revisited. At the international level, a domestic immunity arrangement for leadership perpetrators has no standing anymore and is wide open for challenge. As for mid-level and low-level perpetrators, who so often number in the thousands during any atrocity situation, amnesty deals perhaps paired with truth and reconciliation initiatives can be extremely useful tools in establishing peace and stability throughout ravaged societies. But that is a very different issue from what has evolved in recent years to hold leaders accountable for atrocity crimes.