Nathan Schneider’s story “Some Assembly Required,” which traces the birth of Occupy Wall Street, appeared in the February 2012 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

With exactly a week left before May Day, Occupy Wall Street organizers were coming and going from an East Village townhouse. In the basement, enormous banners were being painted for “mutual aid” stations. Upstairs, Ingrid Burrington and Chris Longenecker, both in their mid-twenties, sat on meditation cushions on the hardwood floor of a room where Longenecker and three other Occupiers were living. The walls were covered with posters calling for a general strike, and a record player was spinning an Allman Brothers album. Covering the floor in front of Burrington and Longenecker were intricate maps of New York that Burrington had obtained from the Department of City Planning, then had laminated. As her computer attempted to process a data trove related to the NYPD’s “stop and frisk” policy, she explained to Longenecker how to transfer information from a spreadsheet to the JavaScript code that controls a Google map.

“Does that make sense?” she asked.

“It doesn’t completely not make sense,” he replied.

Since January, Occupy Wall Street’s Direct Action Working Group has been preparing a carnival of resistance for the traditional workers’ holiday of May 1. In addition to plastering the city with posters advertising a general strike for May Day, the members of Direct Action, including anarchists like Longenecker, have helped forge a coalition of community, immigrant’s rights, and labor organizations, joining their partners in spreading the more modest call to “Legalize, Unionize, Organize,” and in planning an afternoon march from Union Square to Wall Street. Starting at eight in the morning, midtown Manhattan will be clogged with teams of “99 Pickets” marching to sites of 1 percent power.

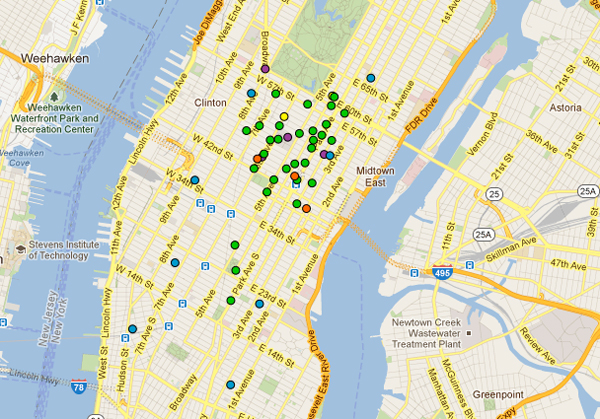

Longenecker had already begun marking these sites on the laminated maps with colored markers: police precincts in blue, pickets that might involve arrests in red, and safer ones in green. Each pickets was numbered, so that the clandestine control center for the march could coordinate the day’s actions. “This has way more moving parts than anything we’ve ever done before,” said Longenecker.

It was fortunate, then, that Burrington was around. “I’m only good at two things,” she’d told me a few weeks earlier, as she showed me a map in Adobe Illustrator of police patrol routes for Union Square. “Organizing large amounts of data in useful ways, and making pies.” Burrington started making maps as a student at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. Charting that city’s patchwork of neighborhoods, with its stark divisions between black and white, rich and poor, she’d come to appreciate the political nature of cartography—how maps shape people’s experience of space and how they thereby wield power over that experience. She later edited a diagrammatic newspaper, the Schematic Quarterly.

She was surprised, when she got involved with Occupy Wall Street, at how little the movement was using maps, so she began charting sites of interest: corporate headquarters, privately owned public spaces, accessible bathrooms. “This is entirely a social movement about geography,” she told me. This line of thought places her within a tradition of resistance that includes the Situationists and their experiments in psychogeography, the Czechs who removed street signs to disorient Soviet troops during the Prague Spring, and the Syrians who changed the names of streets and bridges on Google Maps from ones associated with the ruling Assad family to ones honoring the resistance’s heroes.

Other Occupiers have also begun incorporating cartographic concepts and methods into their protests. For several weeks, a small twenty-four-hour occupation has been roving around New York City, staying at such locations as Union Square, sidewalks in front of banks, and, now, the Federal Hall memorial on Wall Street. Organizer Nicole Carty told me she hopes these “sleepful protests” will change the way New Yorkers experience their city. The idea, she said, is “to map, with our bodies, capitalism all over New York.” The roaming protests, along with acts of civil-disobedience like getting arrested for lying down outside the New York Stock Exchange, represent the first lines of this map. Organizers want to see similar actions across the country, marking the influence of Wall Street throughout the United States. They’ve been talking about creating a “Where’s Wall Street?” mobile app that would allow users to map out and discover Wall Street’s tentacles in their own communities.

Occupiers in Los Angeles, where the call for a May Day general strike originated, also used cartography in their planning. To address the challenges of their city’s vast sprawl, they’ve asked activists to converge on the downtown core in caravans of bicycles, cars, and subway trains along four newly conceived arteries—the “Four Winds”—starting in the north, south, east, and west ends of the county. Their hope is that the Winds will become the basis of future organizing after May Day, linking disparate communities in the shape of a bull’s eye around the city’s financial district.

I asked Ingrid Burrington and some of the other May Day organizers in New York what future maps of their city might emphasize, were the Occupy movement to succeed. “Mutual-aid stuff,” one of them suggested. “Where you can go for resources,” Burrington explained. Then she thought of something else: “I think we would probably create monuments and weird new memorials.” The November 15 police raid that ended the occupation of Zuccotti Park, she said, had seared certain scenes and places into her memory.

I used to wonder myself during the occupation whether a plaque might someday commemorate its kitchen, library, or General Assembly. A few days before the map-making session with Burrington and Longenecker, I had sat with a group of Occupiers on the steps of the Federal Hall memorial, surrounded by NYPD barricades. One of the activists pointed to a fist-sized gash in the side of a building on the other side of Wall Street. Looking at his phone, he read aloud from a Wikipedia page that explained its cause: a 1920 bombing by Italian anarchists that killed thirty-eight people. It was a quiet reminder that Wall Street had had enemies before. The gash was unmarked and unmapped; I’d passed by it many times, and had never even noticed it.