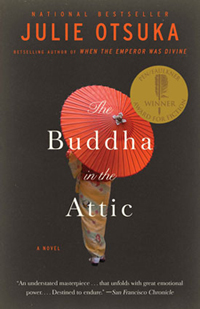

Julie Otsuka is the author of two novels, When the Emperor Was Divine and The Buddha in the Attic, the latter of which was recently awarded the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. The novel traces the lives of a group of Japanese “picture-brides” from their journey to the United States in 1917 to their departure for the internment camps of World War II. Narrated in the first-person plural, the book’s eight chapters focus on important moments in the women’s lives, such as their first nights with their new spouses. One of these episodes, “Whites,” was excerpted in the August 2011 issue of Harper’s Magazine. We put six questions to Otsuka about the novel and her prose:

1. Your first novel, When the Emperor Was Divine, followed the story of a family’s experience in one of the internment camps created by the U.S. government for Japanese-Americans during World War II. With The Buddha in the Attic, you stepped backward in time and outward in voice. In a past interview, you called this unique, first-person plural voice a “choral narrator” and likened its creation to the arranging of a chant. What advantages or obstacles did you encounter with it? Did it force any changes to your usual method of composition?

Using the first-person plural allowed me tell a much larger story than I could have told otherwise. I had tried, in an earlier version, to tell the story from the point of view of a single picture bride, but the writing felt flat and uninteresting. I had run across so many fascinating stories during my research, and I wanted to tell them all—using the “we” voice allowed me to weave them all in.

The voice did pose certain grammatical challenges, and it was a very different way of composing than I was used to. Normally I would follow a single character from A to Z, through a series of interconnected, chronological scenes. But in Buddha, there is no unity of place or character—all of the stories are being told simultaneously in cities and towns and labor camps throughout California. So I’d say one of the biggest challenges was to create these parallel worlds and bring them to life simultaneously on the page.

2. You frequently combine precise details with textured, lyric settings—I’m thinking, for example, of the “rose-patterned saucer that was the exact shade of green as our mother’s jade Buddha,” which comes shortly after your description of the women’s dream of “a pretty white house of [their] own on a long, shady street with a garden that was always in bloom.” These juxtapositions of careful details with vibrant strokes evoked visual works for me—Seurat’s accumulations of dots or Van Gogh’s brilliant lines. You studied art as an undergraduate and worked at becoming a painter for several years—do you ever conceive a scene as you would a painting, or do the two arts come to you differently?

I do tend to think very visually, though I’m not usually conscious of doing so, it’s just how my brain seems to work. It’s like my mind’s a camera. I often have to see a scene in my head before I can begin to describe it on the page. And I think that painting and writing are very similar in terms of process. If you’re a painter, you go into your studio and loosely sketch out a scene on the canvas, then gradually bring up the details. If you’re a writer it’s the same thing. You go to your studio (or in my case, my neighborhood café, which is where I do all my writing), you rough out a scene, it’s loose and fragmented and messy, and then you gradually bring it into focus.

But Buddha also came to me aurally—through the rhythm of the language—as well as visually. I was very tuned in to the sound of the words and where the accents fell, and could sometimes hear the rhythmic pattern of the next sentence I wanted to write before I knew the exact words to drop into that rhythmic pattern. So every scene had to work on both levels: the seen and the heard.

3. The book has the broad contours of historical fiction, and your acknowledgements attest to how much historical research you did, but its narrative structure and voice aren’t typical of the historical-fiction genre. Were you concerned about innovating while you wrote, or did your innovations come about more naturally?

No, I wasn’t thinking about genre or how a story “should” be told while I was writing the book, I was just . . . writing the book. And I never thought of myself as being an innovator. I do believe that every book just has its own organic form—and the voice I chose for Buddha was the voice that seemed right for the material. Once I decided to use the “we” voice, it seemed like the most natural thing in the world. I don’t think it was until I finished the book that I realized it was a little different. Which is probably best. One doesn’t want to get too self-conscious while writing, you know.

4. Loss and disappearance pervade the book, but most of the women confront their losses stoically. One of the most powerful moments of the book for me was a passage portraying some of the women as so obsessed with their work in the fields that their lives have otherwise become hollow, ending with the line, “And often our husbands did not even notice we’d disappeared.” Why did you want to deal with these themes, and how did you try to evoke the feeling of absence that loss entails?

While researching these women’s lives, I was struck by how much loss they suffered. It was almost unimaginable. And yet, they kept on going. They simply endured (a very Japanese attitude—you stick it out and you don’t complain, because complaining would be unseemly). And, really, what choice did they have?

I was also struck by how little we hear about the lives of women in the official historical accounts. Most of history is written by men, and about men. So I wanted to give a voice to these invisible unsung women—the ones who didn’t make it into the pages of the history books—because their lives are just as heroic and dramatic (if not more so) as the lives of the men who “officially” make history.

How did I evoke the feeling of absence? Simply by describing what happened. There was no need to overplay the material. You get this accretion of detail in story after story that becomes overwhelming at a certain point—loss upon loss upon loss.

5. So many of the individual stories and lines feel steeped in both historical detail and profound emotion. Did you come across any particular stories in your research that really stood out or felt personal to you?

Because most of the stories I ran across in my research were of people treating each other badly, what stood out for me were the occasional acts of kindness: the school principal who took the day off to drive to the station and say goodbye to his Japanese students as they were leaving for the camps; the German woman who brought her Japanese neighbors a cake on the morning of their departure; the white family who took care of their Japanese neighbors’ nursery for them while they were away. These stories—because they were the exception—were stories that I personally needed to hear. And I’m not sure why, but the stories about what happened to people’s animals really got to me too. Perhaps because animals are so powerless, even more powerless than the people I was writing about.

One image that has continued to haunt me: the dogs on Bainbridge Island running after the Army trucks that were taking away their masters—Japanese families who had lived on the island for years and were now being sent to the camps. Also, my own grandmother killing all the chickens in her yard the day before they left—she snapped their necks one by one with a broomstick. I remember my mother saying to me, “It was a mess.” And I remember her describing to me the sound of the metal gate clanking shut behind her when they arrived at the assembly center. Such a little thing. The clank of a gate. But it stayed with her all those years.

I also remember her asking me, when I came back from a visit to the camp in Utah where she had been interned during the war, “So, what did you think?” And then, before I could answer, she said, “It was pretty depressing.” And then she changed the subject.

6. After the Japanese-Americans are taken away to the camps toward the end of the novel, the perspective suddenly shifts to a totally different collective voice—that of the white Americans the women knew who so awed and abused them. The Americans, we see, have lost not only perceived enemies, but friends and employees; you reveal, through them, the thoughtless way people worry, grieve, hate, and forget. It’s powerful and brutal, especially a moment I loved, when a boy who has discarded a vanished Japanese-American friend’s sweater receives a letter inquiring after it. The boy doesn’t sleep for three nights. Why did you end the novel in the heads of other Americans?

I actually knew my ending from almost the moment I started writing the novel. It grew out of a piece of unfinished business from my first book. While touring for Emperor, I spoke to a number of Californians who’d been alive during WWII who told me that they had “no idea” about the camps. And I wondered how this could be true. How could you not notice that your neighbors and classmates had suddenly disappeared? The evacuation notices were posted everywhere and hard to miss. One woman who’d been in the first grade when the war broke out told me that she had sat next to a Japanese-American girl in class. One day that girl just disappeared, and she always wondered what had happened to her. So I was especially interested in how the white children processed the disappearance of their Japanese classmates. What did their teachers tell them? What did their parents tell them? I also remember my mother telling me that when she returned to Berkeley from “camp” after the war, none of her classmates asked her where she had been for the past three and a half years. These were classmates she’d been with since the age of five. They just said hello to her as if nothing had happened. And again, I thought—what were they thinking, where did they think she had been?

So the idea for that last chapter was something I’d wanted to write for a long time—I wanted to explore that moment “right after” (the Japanese had disappeared), from the point of view of the white townspeople left behind. And at a certain point I realized it could be the perfect, unexpected ending to my new novel.