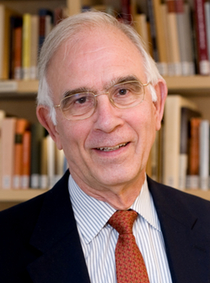

The last years of Mozart’s life and the prodigious and important works he created during them have been heavily romanticized in the musical literature. Now, one of this generation’s leading musicologists wants to set the picture straight. In his new book, Mozart at the Gateway to His Fortune, Harvard professor Christoph Wolff carefully reconstructs Mozart’s patronage relationships, explores his engagement with Bach and other masters of the polyphonic tradition, and reassesses Mozart’s impassioned turn toward sacred music. I put six questions to Wolff about the book:

1. Many depictions of Mozart’s life, for instance Alfred Einstein’s, have tended to divide it along emotional or psychological lines. But in defining the composer’s final mature period, you focus on an employment relationship, with the court in Vienna. Can you explain why?

This question actually speaks to the raison d’être of the book: my scholarly discomfort with the traditional view of Mozart’s decline toward the end, along with the downplaying of the imperial appointment. Since the various “artificial” periodization attempts have generally been more misleading than helpful, I wanted to be on firmer ground. Ever since moving to Vienna, Mozart was seeking employment at the imperial court, and he expressed much frustration that it took so long. Finally, when the emperor appointed him in December 1787 to his elite private chamber ensemble as “Kompositor” and performer, Mozart’s status was given an enormous boost. As this appointment coincided with the emperor’s involvement in the Turkish war—which led to his illness and death in early 1790, and therefore was never fully consummated—Mozart’s perception of his imperial elevation nevertheless had a direct impact on his competitive spirit. Unequivocal and more concrete than any psychological speculation, the lens of the external biographical event helps to redefine the four years from 1788 to 1791 as an unusually productive and innovative period, signaled, not entirely coincidentally, by the grand symphonic trilogy from the summer of 1788.

2. You previously suggested that Mozart’s piano concertos owed a great deal to Bach’s inventions, and in your new book you say that Mozart spent his final years near the center of a “Bach cult.” How did this influence Mozart’s prodigious output in his last years?

Mozart biographers and scholars of his music continue to seek plausible clues that might help explain the conditions leading to the composer’s final illness and death. According to the prevalent view, his premature end appears as a nearly predictable and almost inescapable eventuality. It is usually attributed to a combination of total exhaustion, desperation over failing musical success, and worry about financial ruin. Mozart’s death is often thought of as a personal catastrophe foreshadowed by, and reflected in, some characteristics of his late works—ignoring that a composer in his mid-thirties can hardly write “late” works. Yet, as irrational as it is, the perception of a valedictorian spirit in the music of the final years is still widespread and well accepted.

—From Mozart at the Gateway to His Fortune: Serving the Emperor, 1788–1791. Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton & Co., © 2012 Christoph Wolff.

Bach had certainly always been a “household name” in the Mozart family. In the later Viennese years, however, Mozart encountered among his principal patrons quite a few who were admirers, some even students of Bach and who possessed Bach scores (e.g., of the B-Minor Mass) unknown to Mozart. His was no ordinary audience, but one apparently full of high expectations, which presented a challenge to him. This situation is not only reflected in a more ambitious format and more sophisticated compositional design, but also in his 1789 “pilgrimage” to Leipzig, as well as some deliberate musical references to Bach, like the finale of the Jupiter Symphony and the Song of the Armed Men in the Magic Flute.

3. Mozart sought and secured an appointment at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in his last years; you note this and discuss his development of a new style of sacred music. What works mark this transition, and how do you characterize them?

After the death of Joseph II, Emperor Leopold lifted the restrictions his brother and predecessor had imposed on church music with orchestra and vocal soloists. This encouraged Mozart to re-engage in sacred music, an activity he had abandoned after leaving Salzburg, and to take on responsibilities at the cathedral in Vienna. Moreover, his sacred-music interests were neutralized by court Kapellmeister Salieri’s apparent apathy in this regard. By a decree issued in May 1791, Mozart was appointed substitute to the ailing cathedral Kapellmeister Leopold Hofmann, with a promise to succeed him. Although only two works, the “Ave verum” motet of July 1791 and the unfinished Requiem, originated after this appointment, both show significant differences from Mozart’s earlier sacred music. In particular, they emphasize genuine vocal qualities and choral textures at the expense of a previously more-dominant instrumental score, and thereby not only accentuate the text and its meaning, but also assume a more ceremonial religious character.

4. Alongside the traditional sacred works like the Requiem and Ave verum corpus, Mozart also evolved a pathos-laden style for some of his Masonic music in the later period—the funeral music, The Magic Flute, the E flat major symphony, some cantatas. How do you relate the Masonic music to Mozart’s traditional sacred output?

As for Mozart’s personal definition of a “higher pathetic style of sacred music,” he found it important, in the interest of continuity, to fit his own work into the tradition of church music in general and the funeral genre in particular. Significantly, however, he did not integrate the classical vocal polyphony of the Palestrina-Fux tradition into his new concept, even though this style had become an integral part of church music practices in Vienna during the late eighteenth century. But Mozart looked back only as far as the generation of Bach and Handel, thereby bringing something entirely new into the Austrian tradition. Anyhow, he was not merely adopting ideas and themes or thinking of copying earlier style models as such. Rather, his primary intention was to integrate certain manners of traditional counterpoint into his music in order to enrich its stylistic vocabulary, refine its texture, and to enhance and strengthen its expressive prowess. The deliberate exploration of polyphony, in the manner of Bach and Handel in particular . . . led to a wholly new kind of form, style and sound image, with nothing backward-looking about it.

—From Mozart at the Gateway to His Fortune: Serving the Emperor, 1788–1791. Reprinted by permission of W.W. Norton & Co., © 2012 Christoph Wolff.

The solemn qualities of Mozart’s Masonic works relate very closely to the characteristics of sacred music and, therefore the two share many stylistic features. The March of the Priests in the Magic Flute as well as Sarastro’s arias represent perfect examples of the crossover approach, but so does—on a different level—the Andante of the E flat major symphony in terms of its striking combination of melodic-textural simplicity with extreme, yet reticent, harmonic refinement.

5. What conclusions do you draw, especially on the basis of Mozart’s thematic catalogue, about his practices in composing?

The thematic catalogue, begun in 1784, indicates the composer’s interest in keeping track of his finished works. It does not list the many works in progress, i.e., Mozart’s scores of unfinished works, which contain both shorter and longer drafts of projected movements that he kept on file for eventual completion. The many blank pages at the end of the thematic catalog serve as a reminder that the large body of surviving fragments needs to be taken into consideration when judging Mozart’s overall compositional activities in general and his unusual creative process in particular. For the fragments document his practice of composing a piece in his head, and when not needing it right away, of keeping a record of its incomplete stage on file. Alas, the fragments themselves offer not more than a glimpse at many sparkling musical ideas whose full evolution is forever gone.

6. Is it meaningful to speak of an “imperial style” for Mozart; if so, what differentiates this style from the earlier Mozart?

The term is not meant to parallel Beethoven’s “heroic” or “middle” period style, but derives from Mozart’s imperial appointment. By implication, it designates a related and evident stylistic trend that manifests itself primarily in the demonstrative grand gestures, larger formats, more ambitious designs, and more sophisticated compositional techniques. Having shed his “wunderkind” image, the composer finally goes public by presenting himself with a seriously innovative approach in all major genres of music.

Wolff writes that Mozart’s Sonata in F-major, K. 533 (1788) “has no parallel among Mozart’s keyboard sonatas,” and that it “demonstrates a primary interest in constructive thinking and transparent design as well as in intellectual and material penetration of the chosen musical substance” that characterizes his late period. Listen here to a performance of the sonata’s two movements by Mitsuko Uchida: