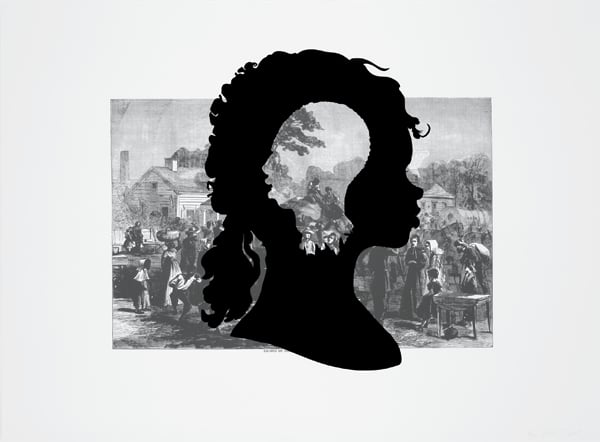

The July 2012 issue of Harper’s Magazine features a portfolio of images by New York artist Kara Walker from her series Works from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). The series, which was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art this spring, consists of fifteen lithographs and screenprints created using enlargements of woodcut prints from the titular book. Featured in the magazine portfolio are four images, all named after their source images’ captions: Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta, Cotton Hoards in Southern Swamp, Occupation of Alexandria, and Pack-Mules in the Mountains.

First published in 1866, the lavishly subtitled Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War: Contemporary Accounts and Illustrations from the Greatest Magazine of the Time, with 1000 scenes maps, plans and portraits comprises 836 large-scale pages. The anthology’s editors, Alfred H. Guernsey (Harper’s Magazine editor from 1856 to 1869) and Henry Mills Alden (editor from 1869 to 1919), described their aims in its preface:

We have undertaken to write the History of the Great Conspiracy which finally culminated in the Great Rebellion of the United States. Our task was commenced during the agony of the great struggle, when no man could foretell its issue. We purposed at the outset to narrate events just as they occurred; to speak of living men as impartially as though they were dead; to praise no man unduly because he strove for the right, to malign no man because he strove for the wrong; to anticipate, as far as we might, the sure verdict of after ages upon events.

As Walker shows, the verdict of after ages remains unsettled. Her series imposes the solid black silhouettes of African-American faces and figures over some of the black-and-white woodcuts chosen by Guernsey and Alden to accompany the anthology’s text. Walker, who lived and studied in Atlanta in the Nineties, is widely known for this silhouetting technique, but this is the first time she has set it so directly against the historical record. “These prints,” she says, “are the landscapes that I imagine exist in the back of my somewhat more austere wall pieces.” She explains that her aim was to suggest perspectives left out of the record—and indeed, her shadows seem to reflect upon, react to, even alter the events Harper’s was attempting to depict “just as they occurred” a half-century ago. Walker’s juxtaposition of shadowy, often blatantly stereotypical features of African-American figures with precise, detailed prints portrays anew the racial history of the South, and reflects, in its way, on contemporary America.