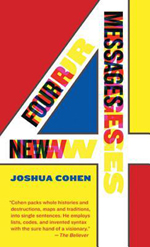

Joshua Cohen’s new story collection, Four New Messages, was published on August 7 to wide and deserved acclaim. The book’s four independent but stylistically and thematically harmonious stories are an extraordinary blend of the familiar and the cutting-edge, addressing ancient human preoccupations in an animated, elastic style that captures the distracted and alienated character of our time. The week after its release, I sat down with Cohen at his apartment in Manhattan to discuss writing, the horror and splendors of the Internet Age, and whether the codex, privacy, and the human imagination are doomed. “I’m more interested in good writing than good ideas,” he said, “because I believe good writing is the good idea.”

Joshua Cohen’s new story collection, Four New Messages, was published on August 7 to wide and deserved acclaim. The book’s four independent but stylistically and thematically harmonious stories are an extraordinary blend of the familiar and the cutting-edge, addressing ancient human preoccupations in an animated, elastic style that captures the distracted and alienated character of our time. The week after its release, I sat down with Cohen at his apartment in Manhattan to discuss writing, the horror and splendors of the Internet Age, and whether the codex, privacy, and the human imagination are doomed. “I’m more interested in good writing than good ideas,” he said, “because I believe good writing is the good idea.”

1. Your new story collection is called Four New Messages. How is a message different from a story?

The title was meant to evoke the Internet: You’ve got mail! I was thinking about messages that can be very personal, or very impersonal, but both processed and presented in the same way, using the same template. Letters received from different grandparents, they look different, parents’ voices sound different, but all my friends write to me nowadays in Times New Roman 12-point. With standardization of presentation comes standardization of expression. This, to me, is one meaning of message.

I also thought to use the word for its late-Tolstoy presumption—How Much Land Does a Man Need?—or urgency—Lenin’s What Is To Be Done? Now I’m not ready to take off my shoes and go a-begging, exhorting everyone to move to the New Jerusalem, but I can’t shake my fascination with that conviction, with that style of preachment—messaging the masses.

2. Through wordplay—repetition, rephrasing, rhyming—each of the stories in the book carries an active, energetic sense of “noise” on the page. In addition to the narrative, the interaction of language tells a story of its own. How should this style shape the reading experience? Should your stories be read aloud?

I write everything by saying it aloud. I believe in the ear. Most of our narrative history has been oral/aural. It’s the tradition of sitting around a fire, listening to lore, hearing myth, but then the development of writing systems, and of publishing systems, caused and confirmed this transition to the visual/manual, or the graphic/manual. We became more eye-and-hand-oriented, creatures crouching alone, reading off the page. The Internet extends this, but reaches back in the other direction to reincorporate the older sensorium—the mouths and ears coming out of retirement so that everything’s engaged now but, perhaps, the olfactory. I don’t expect my readers to read aloud—but I do hope to remind them of the literary primacy of their mouths and ears.

The repetitions are, in my mind, linked to the idea that the Internet is conceptually vast, but you end up spending the bulk of your time visiting the same sites again and again (or perhaps this is just my own practice). I’m not especially interested in the variety of the Internet; rather I’m interested in the human experience of the promise of variety, a promise fulfilled only by a similarity or sameness, and the idea that the computer seems to license every option of virtuality, while our own humanity seems limited, or to self-limit, through laziness or shame, to the same thing every day.

3. As you said earlier, the Internet contains endless possibilities, and it also sort of creates more and more identities. You are who you are, but then there are endless versions of you online who never disappear and who don’t age with you or ever go away. Sometimes, you’re not even in control of them, as is the case for Richard Monomian in “Emission.” [After a college student publicly blogs about something disgusting Monomian told her he did at a high school party, he achieves the saddest, most humiliating sort of Internet fame as he—and his name—become mocked and shamed all over the world wide web. “Emission” then becomes the story of Monomian’s difficult, often futile feeling quest to clear his name in cyberspace.] How do we negotiate between—and manage—our many Internet identities?

That’s certainly something everyone’s faced with. It used to be that if you raped or killed someone, you fled to a different city, or a different country. Images became easy to replicate, which made them easy to disseminate, which is now allowing them to be made easily searchable; and, concomitant with this history, the degree to which you’ve become registered with the state, and even with the globe, has obviously increased, through technologies increasingly invasive not just of citizenship but of civilization too (your genes)—even so, most of us are still in control of our online representations. Alternately, most of us can and will adjust to being represented as different from who we are, or who we hope to be online: “I’m not as bald in that pic my friend put up”; “I’m not the guy in that vid—we just have the same name and I got tagged.”

But I had another idea while writing “Emission,” which was, “What if I wrote a version in which a guy puts up something incriminating of himself? What if the blogger who betrays him is unnecessary? What if Monomian puts something up about himself—maybe he’s drunk or stoned, maybe’s he lonely—and then once he’s sober and realizes what he’s done can’t take it down because he’s forgotten the password to the blog he hastily created, or the blog’s host can’t be contacted.” That, to me, is a much more interesting situation—much more psychologically nuanced—but very difficult to do in the fiction I was trying to write, which was to be every bit as speedy and impatient as Internet use. Every bit as schematic too. With that idea, though—Kafka 2.0—the character would have no one to blame but himself. He would have convicted himself, not in a penal way, but with embarrassment, humiliation, regret.

from “Sent,” in Four New Messages:

He opened a window—not an actual window onto Creationdom, just something we call a window. An opening into a new otherness or alterity, not to make it sound any better than the depressing it was. Though it was good the motel got such good service—he was connected, stably online, for a fee. To be added to his bill. Spending so much money, so much of it not his.

He was tired of unfinishing delinquent assignments, tired of rereading homework done in a rush. He entered into the browser the address, which he wouldn’t store in memory. Instead he’d stored it in his own memory and supplied it every time. Daily, often twice: www., the name of his preferred diversion, .com, which stands for “commerce”—he pressed Enter, depressed, also called Return.

4. Lena Dunham’s new show, Girls, got a lot of attention for its frank and sometimes disturbing portrayal of sex. In an interview, Dunham said “When I first started kissing boys, I remember noticing things, certain behaviors, where I thought, ‘There’s no way you learned that anywhere but on YouPorn.com. There’s no way any teenage girl taught you and reinforced that behavior.’ ” “Sent” depicts a world where men’s ideas about women and sex are similarly informed by Internet porn.

There’s a section in “Sent” where I write about how the character’s father, if he masturbated, masturbated to paper: magazines somewhat glossier than Harper’s. He had to go down to the newsstand or check the mail for unmarked packages, butcher-paper-wrapped. Now the distribution mechanism/point-of-sale sits on the desk in plain day, and not only that, but it can feature windows showing the most violent, misogynistic porn, which are indistinguishable, in terms of conceptual framing, from a Word document of downloaded Jane Austen. I think this can make you believe that because X and Y, or X and XXX, are equally available, they’re equally permissible too. It’s a profound element of confusion for everyone—not least for men of my generation.

It’s wildly ironic, or tragic, that you have my generation—the children of baby boomers—being raised in a manner more egalitarian and more equal in spirit than any other generation in American history—two-income households, men demanding as vocally as women have ever demanded that women receive equal pay/benefits/promotions, etc. So you take this generation of men that has become, in a sense, feminist, even feminized (but that’s a different issue), and you give us access to all this hairy, sweaty, monstrously subjugating evil—featuring woman who, as often as not, appear to be enjoying themselves—and what’s engendered is a type of sexual or relationship schizophrenia. I remember when I was in school, some college not mine had all these date-rape cases, and the policy the administration recommended was, if you’re on a date with a woman, you have to ask, “Can I kiss you?” “Yes.” “With tongue?” “Yes.” “Can I touch your breast over your shirt?” “Yes.” “Under your shirt but over your bra?” “Yes.” And so on: step-by-step consent—nothing more persnickety, nothing more unsexy. To take that degree of responsibility and agency on both sides—where nothing is left gray, and nothing is left to surprise either party, either positively or negatively—and to face it with these grosser intimations, or “suggestions for use”… I have the feeling that men feel deprived, in a sense, of something that never existed.

5. In “The College Borough,” Greener, the father’s writing teacher, says “We’re the first nothing generation, we’ve got nothing to write about and no one to read it, everyone too busy getting technologized, too harried with degrees.” It seems like every generation since the Dead Sea Scroll communities—and probably before them, too—felt this way, like they’re the ones who will really experience the end.

Absolutely. It’s the privilege of every generation to think itself the last—and every generation has been marked by someone writing something like that. Or by a sentiment even more Trotskyish—every revolution must revolt—implying, of course, that every generation must resolve itself, necessarily, only in failure. Part of that line of dialogue—I have to stress, of dialogue—from “The College Borough” is countenancing that, but I was also thinking about some of the issues confronting the physical book, the codex. Not every generation has thought the codex will disappear. Two covers stuffed with paper with words on both sides of each page—it’s had a good run. Then a walk, then a crawl. It will be survived, most immediately, by $8,000 Taschen art editions, which are more furniture with which to decorate your furniture than anything else.

6. Going back to the folktale discussion, “Sent” begins as a folktale, but then there’s a very clear break. You write: “This story will not end as it began. No more trashy telling like this, no more folktales. Here is a folktale that will end as a story, as a novel if we’re lucky, but still nothing to compare to the audio/visual.” Along the lines of this hierarchy, I recently heard about a new kind of storybook that’s being developed with extrasensory components: a projector to create a visual mood, built-in speakers to give background noise. If it’s a story about the ocean, you’ll hear ocean sounds. How do these immersive features change stories?

In “Emission,” I include that brief quote about Raskolnikov: “His face was pale and distorted, and a bitter, wrathful, and malignant smile was on his lips.” That’s the most notable physical description of him in all the hundreds of pages of Crime and Punishment. If you read through the history of literature, it’s difficult not to note this slow, but seemingly inevitable, seemingly even conscious, accretion of detail. Characters in the oldest literature—Sumerian lit and the Bible, fables and folklore—are almost never physically described, and, of course, God “Himself” is never physically described. But then as you approach Antiquity, you encounter characters described by epithets, where one quality, frequently not even a physical quality, distinguishes them, rendering them an archetype for same. As you read on and into “fiction,” you find increasing physical description—archetypes profaning into types, characters aware of their own bodies (which is to say, psychology: mental or emotional description)—and with that comes, seemingly inevitably, seemingly consciously intended, a perceptible decrease in the reader’s imaginative opportunities. There’s just less space, less of a place, for the reader to co-write the book by filling in the blanks—the blanks have all been filled.

Take one of my favorite describers, Nabokov—who hated Dostoevsky, and regarded him as incompetent. Lolita prevents you from imagining Humbert Humbert and Lolita, and compels you instead to just see/hear/synestheticize how Nabokov himself intends them to be seen/heard/synestheticized—not just that, but Nabokov gives you “his” Humbert, and “his” Lolita, alongside “Humbert’s” Lolita and even “Lolita’s” Humbert. The reader, then, is exiled if not from the book then from his or her own importance to the book. Forget becoming involved with characters; the reader’s better involved with the author: the true hero, and heroine, turns out to be Nabokov—naughty Volodya!

Take one of my favorite describers, Nabokov—who hated Dostoevsky, and regarded him as incompetent. Lolita prevents you from imagining Humbert Humbert and Lolita, and compels you instead to just see/hear/synestheticize how Nabokov himself intends them to be seen/heard/synestheticized—not just that, but Nabokov gives you “his” Humbert, and “his” Lolita, alongside “Humbert’s” Lolita and even “Lolita’s” Humbert. The reader, then, is exiled if not from the book then from his or her own importance to the book. Forget becoming involved with characters; the reader’s better involved with the author: the true hero, and heroine, turns out to be Nabokov—naughty Volodya!

All of which is to say that while I’m fairly sure that multimedia accompaniments to a book would only be an extension of this process, or a further impediment (oxymoron!) to the imagination, it’s ultimately more interesting for me to think about how literature itself—unenhanced lit, let’s say—can, or will, continue. Let’s conclude by noting that no other medium can do what’s just been done in this Q&A—perhaps badly on my end, but I’ve tried—no other medium can deliver such effective critique. In the end, writing will survive—sadly not for its beauty nor its solace, nor for its plots nor characters—rather because it is the medium of criticism.