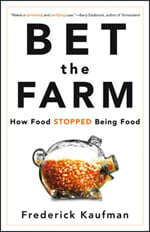

There is enough food grown in the world to feed its entire population, yet approximately 1 billion people go hungry every year. With this in mind, food journalist and Harper’s Magazine contributing editor Frederick Kaufman went searching for the variables that make a slice of pizza cost so little. Demystifying the complex system of wheat futures, he traveled to farms, labs, manufacturing facilities, and Wall Street, where he uncovered who cornered the wheat market in 2008 and created the food bubble. I hungrily asked him six questions about his new book, Bet the Farm: How Food Stopped Being Food.

1. Wheat prices have been erratic in recent years, and this summer they rose again, from $264.36 per metric ton in May to $349.4 per metric ton in August. The current price is only $90 below the 2008 peak you mention in your book. Left untouched, will the market become more volatile as time goes on? What does this mean overall to the average consumer in America and those who depend on American cereals abroad?

From Bet the Farm:

“The wheat of ancient Egypt became the currency of ancient Egypt, the power behind the credit of the nation’s central bank, the marrow of its financial system. And thousands of years after the last pharaoh, grain stilled ruled. When the price of wheat spiked in 2011, hunger, violence, and political turmoil descended like a biblical plague, and the result was revolution” (115).

We are ten years into a global food crisis, and while 17 million American families do not have enough to eat, the rest of the country has no clue. For 900 million people on the planet, hunger is a given. And while that number is flat-out apocalyptic, only the activists and the military seem to get it. Problem is, while the numbers boggle the mind, what economist call the “price signal” is still too weak for the average consumer in this country to care. Sure, that box of Wheaties is getting a little slimmer, and that gallon of milk a little pricier, but we are still paying 10 to 12 percent of our weekly take-home pay on food. And that percentage has stayed roughly the same even though the price of global grain has almost tripled since 2002. Why? Because American wheat is subsidized wheat, and when we pay for a packaged good, we are mostly paying for the packaging. In a country like Egypt, on the other hand, the percentage of weekly take-home pay devoted to food has surpassed forty, and people are just as apt to purchase wheat as Wheaties.

Let’s say the price of food doubles in the next twenty years. The Arab Spring will seem like a pep rally. And no doubt, grain prices will stay volatile. Every day, three times as much speculative money is bet on the volatility of imaginary grain on the futures market as money is spent on the actual stuff. The global grain markets have attracted the attention of the investment bankers, the hedge-fund managers, and the sovereign wealth funds. And the price of global grain is “discovered” on the futures markets. Every savvy money manager knows that, down the line, food will only become more “valuable”—i.e., more expensive.

2. Through the first half of the book, you’re obsessed with finding the purest form of food, in an attempt to understand why food operates as it does economically and why that causes people to go hungry. You stare, awestruck, at DNA sequences, spreadsheets, and stock-market prices; then, while visiting the University of California–Davis Plant Transformation Laboratory, you see this message scrawled on a bulletin board: nothing is real. This journey reminded me of the old argument pitting the Platonist’s idea of forms against the Aristotelian’s demand for empirical evidence. You end up suggesting that considering food anything other than physically tangible food is morally wrong. Why?

That great philosophical debate—nominalism versus realism—has become ever more relevant in our age of head-over-heels romance with the virtual, the indexical, and the derivative. The futures markets trade a nominalist version of corn and soy and wheat—a version that consists of promises to buy and sell imaginary grain. For more than a hundred years, these markets allowed people in the food business, the so-called “bona-fide hedgers,” to manage their risks and stabilize the natural peaks and valleys of a seasonal entity (i.e., grain) that we must have every day (i.e., bread). But since 2008, hundreds of billions in new speculative money have poured into these markets, upsetting their equilibrium, sending false price signals, increasing volatility, and allowing all manner of insider-trading abuse. The commodity markets have been subverted by a slew of new derivative products, and the price of imaginary wheat has come to control the price of the real thing. So, yes, ideal wheat has become the enemy of real wheat. Whenever we understand food as an index or a derivative, it has stopped being food. Investors may be gladdened when the value of their investment accrues, but when that investment is food, profits for a few mean hunger for many.

3. Paul Ryan’s 2013 budget proposal recommends cuts to major welfare programs like food stamps and unemployment. He claims that the war on poverty should fix the causes, not the symptoms. At the same time, he would cut federal farm support by 300 million over ten years and reform the “open-ended nature of government support for crop insurance.” What might severe cuts in these areas mean for American society? What risks could this run, historically speaking?

The history of hunger shows that the cause of starvation is not lack of food. People starve because they cannot afford food. Food stamps are a very effective way of stopping hunger, as is unemployment insurance and social security. More Americans than ever are relying on food stamps. So who is Paul Ryan kidding? What kind of effect does he foresee when 17 million American households experience food insecurity? A middle-class mom or dad is not, by nature, a revolutionary. But $20 a pound hamburger and $10 a quart milk will make them so. Everyone in the military and the CIA knows that the best way to foment unrest in a country is to increase food inflation and food insecurity. And since 2008, we have seen more than sixty food riots across the world, and more than one regime change. Would Paul Ryan like to lead the charge?

When it comes to crop insurance and other supports, we have to separate the farmer from agribusiness. One reason agribusiness has not been vertically integrated is that industrialists do not want to bother with the risk of putting seeds in the ground and praying for rain. And while farming may be for gamblers, national security rests on a steady and reliable food supply. Historically, American has understood the need to support farmers. The country has enjoyed years of prosperous harvests of inexpensive wheat because of federal dollars spent on agricultural education and outreach. Washington is right to support those in a high-risk business essential to our national security and international trade. History has shown that when farmers go belly-up, the effects reverberate throughout society. The last thing we want in these days of drought, flood, and climate change is for this country to become dependent on Argentina, Brazil, and Russia for our daily bread. The import costs will dwarf Ryan’s paltry $300 million.

4. I grew up in California’s San Joaquin Valley, a couple of hours away from the Mullers’ farm in Yolo County, which you visited. Old-time farmers in the area used to say, “Farmers don’t farm to make money; they farm to sell their land and retire.” Agricultural cooperatives, meanwhile, are supposed to corner food markets in the interest of the farmers. From selling their land to selling their food, then, it might appear as though farmers trade futures as well. Can the farmer’s interest in profit margins be just as dangerous as wheat derivatives and futures? After all, you do admit that a farmer who believes he has the most delicious cucumbers in the world “would sell them to a man who planned to shoot them into space if he were willing to pay more than Walmart or Unilever pays.” How much, if any, of the blame of global hunger lies with the farmer?

Half the people on earth are fed by two billion small farmers who are often barely able to feed themselves. These so-called “smallholders” could certainly use a bit more money for their product. And it would appear that in the developing world—where the price of a bushel of real wheat has come to depend on the skyrocketing price of imaginary wheat on the grain-futures market—grain growers must be making a killing. Unfortunately, it is not the farmer who pulls in windfall profits on the futures exchanges. The speculators and index-fund managers have reserved that money for themselves. And since the entire commodity complex has been subverted by hundreds of billions of new speculative money, everything a farmer needs to farm has become more expensive. Even as the price of grain goes up, farmers must pay more for their fertilizer and diesel fuel, the so-called “inputs” of the enterprise. Farmers rarely sell their wheat at the height of the market, unlike the world’s largest grain warehousers, Cargill and ADM, transnationals that hoard their wheat in global silos and wait for the optimal time to sell to the highest bidder—Saudi Arabia, perhaps. Or Japan. So while it is true that a farmer will sell to the highest bidder, the reality is that the stampede toward the financialization of food has left the farmer in the dust.

5. Michael Pollan and other activist food writers’ ideas have begun to permeate American culture. But where others tend to vilify industrial food systems, your book seems to take industrial food as a given, and indeed as not necessarily bad. Where do you think many of the current arguments about the way we consume food go wrong? And can industrialized food truly feed the world’s hungry and feed us better?

I thought I had a simple question: How can inexpensive, delicious, and nutritious food be available to everyone on earth? I followed a trail from Big Pizza to Big Cheese, Big Tomato, and Big Pepperoni, and discovered that the largest food retailers on earth were dependent on even more monstrous financial forces. I went looking for a slice, and ended up on Wall Street. So, while I admire Michael Pollan, I do not believe the answer to the global food crisis hinges on the choices upper-middle-class American consumers make at the grocery store. Pollan and Eric Schlosser and others have done a good job investigating and informing us about the industrialization of food, but too little has been said about the securitization of the entire system, the pervasive financialization of food.

Wall Street has come to perceive that while currencies and debt markets may not be as lucrative as they once were, arable land and fresh water will possess value going forward. It would be nice to think that buying local and organic will solve the problem—and yes, my family frequents the local greenmarket. But the global food crisis can only be solved if we get the bankers out of the system and begin to regulate the $648 trillion global-derivatives business that has made food into a speculative buy. The problem can only be solved if we can achieve greater transparency in global food reserves, more-equitable international-trade agreements, and reform of plant patent laws that allow companies like Monsanto and Pioneer their monopolistic practices. Smaller-scale, agro-ecological farming methods may be the ultimate solution, but the problem will not begin to go away until we can enforce the idea that the benefit of wheat is not cash.

6. In a scene set at the Rome hunger conference in 2008, you scoff at the large amount of money being pledged to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. It seems as though no one knows where these donations are going, nor what they are doing to solve world hunger. In fact, in the chapter titled “Let Them Eat Cash,” you ask Bill Gates whether donations and food aid programs help or exacerbate world hunger. Why don’t these things seem to help? Where should wealthy donors put their money if they want to help the hungry in sub-Saharan Africa?

Americans like the idea of giving wads of cash and a bunch of excellent advice—and leaving it at that. But in order for our money to have any effect, we must have more respect for the individual needs of the nations at the receiving end of our fabulous generosity. American-style agro-industrial methods mean heavy use of pesticides, fertilizers, and superseeds, but these techniques may not answer the needs of Guatemala or Tanzania. Nor are American-style commodity markets a panacea for developing nations, despite the arguments of Gates and the World Food Program. But the conundrums of transnational donation are fairly simple to parse. In order to have a positive impact, we need to talk less and listen more.