Twenty Little Poems That Could Save America

Imagining a renewed role for poetry in the national discourse — and a new canon

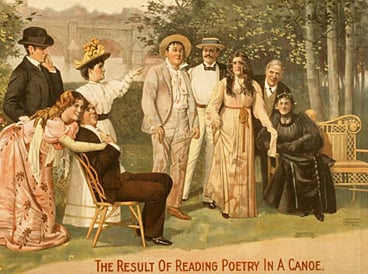

Sappho, by Edwin Austin Abbey. Library of Congress, Cabinet of American Illustration collection

What went wrong? Somehow, we blew it. We never quite got poetry inside the American school system, and thus, never quite inside the culture. Many brave people have tried, tried for decades, are surely still trying. The most recent watermark of their success was the introduction of Robert Frost and Carl Sandburg and some e.e. cummings, of “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and “In a Station of the Metro” — this last poem ponderously explained, but at least clean and classical, as quick as an inoculation. It isn’t really fair to blame contemporary indifference to poetry on “Emperor of Ice-Cream.” Nor is it fair to blame Wallace Stevens himself, who also left us, after all, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” a poem that will continue to electrify and intrigue far more curious young minds than are anesthetized by a bad day of pedagogy on the Ice Cream Poem. Let us blame instead the stuffed shirts who took an hour to explain that poem in their classrooms, who chose it because it would need an explainer; pretentious ponderous ponderosas of professional professors will always be drawn to poems that require a priest.

Still, we have failed. The fierce life force of contemporary American poetry never made it through the metal detector of the public-school system. In the Seventies, our hopes seemed justified; those Simon and Garfunkel lyrics were being mimeographed and discussed by the skinny teacher with the sideburns, Mr. Ogilvy, who was dating the teacher with the miniskirt and the Joan Baez LPs (“Students, you can call me Brenda”). Armed with the poems of Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Richard Brautigan, fifteen-year-olds were writing their first Jim Morrison lyrics, their Kerouacian chants to existential night.

But it never took. We flunked. We backslid.

Sure, there would always be those rare kids who got it anyway; who got, really got “We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!,” got it because they were old souls, preternaturally, precociously alert to the pitfalls of grown-up life, the legion opportunities for self-betrayal, the army of counterfeit values surrounding them. They were the ones who memorized “Dover Beach” and throatily recited it to their sweethearts, in the back seat of a Chevrolet on the night of junior prom, and then once more for select friends at the after-party.

But largely, c’mon — you and I both know — real live American poetry is absent from our public schools. The teaching of poetry languishes, and that region of youthful neurological terrain capable of being ignited and aria’d only by poetry is largely dark, unpopulated, and silent, like a classroom whose door is unopened, whose shades are drawn.

This is more than a shame, for poetry is our common treasure-house, and we need its aliveness, its respect for the subconscious, its willingness to entertain ambiguity; we need its plaintive truth-telling about the human condition and its imaginative exhibitions of linguistic freedom, which confront the general culture’s more grotesque manipulations. We need the emotional training sessions poetry conducts us through. We need its previews of coming attractions: heartbreak, survival, failure, endurance, understanding, more heartbreak.

I have met, over the years, many remarkable English teachers, God bless them, who make poetry vivid and real to their students — but they are the exception. By far the majority of language-arts teachers feel lost when it comes to poetry. They themselves were never initiated into its freshness and vitality. Thus they lack not only confidence in their ability to teach poetry but also confidence in their ability to read poetry! And, unsurprisingly, they don’t know which poems to teach.

The first part of the fix is very simple: the list of poems taught in our schools needs to be updated. We must make a new and living catalogue accessible to teachers as well as students. The old chestnuts — “The Road Not Taken,” “I heard a fly buzz when I died,” “Do not go gentle into that good night” — great, worthy poems all — must be removed and replaced by poems that are not chestnuts. This refreshing of canonical content and tone will vitalize teachers and students everywhere, and just may revive our sense of the currency and relevance of poetry. Accomplish that, and we can renew the conversation, the teaching, everything.

But, I hear some protest, aren’t the old poems good enough? Aren’t great poems enduring in their worth and perennial in their appeal? Love, death, strife, joy, loneliness — aren’t these the recurrent, always-relevant subject matter of our shared songs? In catering to the tastes of the present, wouldn’t we be lowering the caliber of the art we present to our youth? Isn’t this a capitulation to a superficial culture and the era of disposability?

Such questions are beside the point, since poetry is not being transmitted from one generation to the next. The cultural chain has been broken, as anyone paying attention knows. Moreover, the written word always needs renewal. Art must be recast continually. “Dover Beach” and “My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun” are not lost, but instead are being rewritten again and again, a hundred times for each new generation. Culture is always reanimating itself, and when it does so, it validates, reorganizes, and reinvigorates the past as well as the present.

If anthologies were structured to represent the way that most of us actually learn, they would begin in the present and “progress” into the past. I read Lawrence Ferlinghetti before I read D. H. Lawrence before I read Thomas Wyatt. Once the literate appetite is whetted, it will keep turning to new tastes. A reader who first falls in love with Billy Collins or Mary Oliver is likely then to drift into an anthology that includes Emily Dickinson and Thomas Hardy.

The second part of the fix is rather more complicated: in addition to rebooting the American poetic canon as a whole, we must establish a kind of national core curriculum, a set of poems held in common by our students and so by our citizens. In the spirit of boosterism, I have selected twenty works I believe worthy of inclusion in this curriculum — works I believe could empower us with a common vocabulary of stories, values, points of reference. The brief explications and justifications I offer below for nine of these poems are not meant to foreclose the interpretive possibilities that are part of a good poem’s life force. Rather, I hope they will point to areas worthy of cultivation in that mysterious inner space, the American mind.

POETRY TEACHES THE ETHICAL NATURE OF CHOICE

To visualize this poetry-enriched near-future, please imagine that somewhere in the echoey, high-ceilinged meeting rooms of our nation’s Capitol, a congressional committee is in session. It is midsummer in Washington, D.C., and a pitcher of water is on the table, beads of condensation on its side; the ice has melted. A difficult bill is also on the table, one in which the exigencies of the political present must be weighed against the needs of the future — say, for example, that the subsidized production of corn for ethanol might be given priority over other alternatives to gasoline. Too many Midwestern farmers have become dependent on these subsidies. But if policy is changed now, they will suffer.

“It’s like that William Stafford poem,” says one congressional aide. “What’s the title — the one about the deer?”

“Traveling through the Dark,” says a representative from Missouri. The poem begins:

Traveling through the dark I found a deer

dead on the edge of the Wilson River road.

It is usually best to roll them into the canyon:

that road is narrow; to swerve might make more dead.

“That’s the one,” says the aide. “Yeah, that scene where the guy has to decide whether to push the mother deer over the edge of the cliff to make the road safer — even though the deer is pregnant, with a fawn inside her.”

“To swerve might make more dead,” says someone else.

“Yes,” says the first legislator, “here we are, getting ready to choose some lives over others, to clear the road for traffic. Are we going to push the deer over the side of the highway?”

“When you put it like that,” says another, “I think we should wait.”

“That’s not deciding,” says a third congressman, “that’s procrastinating. I say we vote right now.”

Beside that mountain road I hesitated.

The car aimed ahead its lowered parking lights;?

under the hood purred the steady engine.?

I stood in the glare of the warm exhaust turning red;?

around our group I could hear the wilderness listen.I thought hard for us all — my only swerving —,?

then pushed her over the edge into the river.

“Traveling through the Dark” is a well-known poem, but one with legs yet — it offers a lucid ethical dilemma that foregrounds the nature of moral choice.

POETRY RESPECTS SOLITUDE AND SELF-DISCOVERY

Here’s another scenario. A woman, recently divorced from her husband of twenty-five years (he fell in love with his yoga instructor). Living in the city where they shared a life together, she’s discovering what it’s like to be single at fifty. She has a busy professional life and can handle the daylight hours, but the nights are hard, and she’s decided she’d better stay away from wine in the evening. She believes she might be alone for the rest of her days.

One night on the train home, she remembers a poem from tenth grade called “Bamboo and a Bird.” When she gets back to her apartment, she looks it up on the Internet. It’s by Linda Gregg.

In the subway late at night.

Waiting for the downtown train

at Forty-Second Street.

Walking back and forth

on the platform.

Too tired to give money.

Staring at the magazine covers

in the kiosk. Someone passes me

from behind, wearing an orange vest

and dragging a black hose.

A car stops and the doors open.

All the faces are plain.

It makes me happy to be

among these people

who leave empty seats

between each other.

Reading the poem, the divorcée finds focus. “It reminded me,” she says to her friend the following week, “that there can be dignity in being alone. Remember the woman in the poem? She sees everything so clearly because she’s alone.”

“Yes,” says the friend. “She has this pride about being alone.”

“No, it’s not pride, exactly — she just sees what is in front of her. Because she’s tired. She can see because she’s exhausted and by herself. And even though those other people are maybe unhappy and poor, like her, she isn’t responsible for them. They don’t need to be changed. They can’t change. All of them, they just are what they are.”

“No shame, no pity.”

“It’s all right to be lonely, because everyone else is, too. There’s company in loneliness.” She pauses.

“It’s like existentialism with a hand warmer.”

“What about that guy in the poem, who goes past, pulling the hose? We could never figure that out in class. “

“I don’t know what that hose is about. Does everything have to represent something?”

POETRY STIMULATES DARING

At this point, perhaps, you may feel you are on the receiving end of a William Bennett–style sermon on Poetry as Moral Improvement. That intuition is only partially right. Not all of the twenty poems I’ve selected have “instruction” as their agenda. Their usefulness is not so constrained or predictable. Poems are existentially unconventional: though some may look like philosophical fitness equipment, designed for self-improvement, others may look like Siamese cats. Consider, as an example of something unpredictable, the following poem by Kerry Johannsen:

Black People & White People Were Said

to disappear if we looked at

each other too long

especially the young ones —

especially growing boys & girls

the length of a gaze was

watched sidewise

as a kingsnake

eyeing a copperheadwhile hands

of mothers and fathers gently

tugged their children close

white people & black people were said to

disappear ifbut nobody ever said it

loudnobody said it

at all& nobody ever

talked about where

the ones who didn’t listen

went

Johannsen’s poem helps us to name a feature of the social landscape that every American will recognize; it drags into plain sight, and into our common vision, the mystery of race and the ominous way it plays out in our collective social life. It describes the haunted condition that results from repressed knowledge. Moreover, Johannsen’s poem does not avoid complexity in order to create agreement. It does not accuse or judge or cry out; it speaks from the position neither of the oppressor nor of the victim. The poem’s vocal tone is largely one of wonder, which makes it an unthreatening starting point for conversation about a touchy subject.

Alarmed by the rapid erosion of shared knowledge among Americans, the liberal scholar E. D. Hirsch, Jr. took on the role of cultural correctionist with his best-selling book, Cultural Literacy (1987). Hirsch argued that, without the propagation of a common vocabulary — Benedict Arnold, Sigmund Freud, King Lear, “revenue-ers,” the Cold War, Emmett Till, gerrymandering — the American cultural fabric would fray and fall apart. Indeed, unless we continue to renew and supplement our common intellectual property, we can and will get stupider, less comprehending of one another, more disconnected.

The scaffoldings of cultural identity can be either trivial or profound, toxic or sustaining, ephemeral or lasting. The celebrity culture that seems ubiquitous in our moment is a kind of fake surrogate for the culturally significant place gods and myth once held in the collective imagination. The saga of Princess Di, or Michael Jackson, or Amy Winehouse is a shallow substitute for the story of Persephone, lacking the structure to edify but charismatic to many people nonetheless. Just as junk food mimics nutritious food, fake culture mimics and displaces the position of real myth. Real culture cultivates our ability to see, feel, and think. It is empowering. Fake culture makes us passive, materialistic, and tranced-out.

Culturally important artworks establish new benchmarks of relevance, break icons, embody new recognitions for a people and a time. “Diving into the Wreck,” Citizen Kane, “Prufrock,” Glengarry Glen Ross. In poetry, as in other art forms, some works are of significance for cultural reasons, some for aesthetic. Both categories are legitimate, and, of course, they sometimes overlap. Artworks may sometimes lose their shape and resonance, their intensity and relevance, in five years, or ten, or fifty — and what’s wrong with that? The relative value of the “immortal” and the “contemporary” has been the subject of many intellectual battles, but why can’t these categories coexist?

The idealized America envisioned by Hirsch — one shored up by the deliberate revival of old and new traditions — would be one in which poems were part of the civility and pleasure of the dining table, in which guests and hosts staged impromptu readings, in which poems could usefully and naturally be worked into a conversation about anything at all. Is such a culture so far from possible?

POETRY REHABILITATES LANGUAGE

Muriel Rukeyser’s “Ballad of Orange and Grape” can teach us something about the fundamental import of language. Charming and didactic, the poem asks what it means when language is allowed to be unreliable. What, it wonders, happens to culture then?

After you finish your work

after you do your day

after you’ve read your reading

after you’ve written your say —

you go down the street to the hot dog stand,

one block down and across the way.

On a blistering afternoon in East Harlem in the twentieth century.. . .

Frankfurters, frankfurters sizzle on the steel

where the hot-dog-man leans —

nothing else on the counter

but the usual two machines,

the grape one, empty, and the orange one, empty,

I face him in between.

A black boy comes along, looks at the hot dogs, goes on walking.I watch the man as he stands and pours

in the familiar shape

bright purple in the one marked ORANGE

orange in the one marked GRAPE,

the grape drink in the machine marked ORANGE

and orange drink in the GRAPE.

Just the one word large and clear, unmistakable, on each machine.I ask him: How can we go on reading

and make sense out of what we read? —

How can they write and believe what they’re writing,

the young ones across the street,

while you go on pouring grape into ORANGE

and orange into the one marked GRAPE — ?

. . .He looks at the two machines and he smiles

and he shrugs and smiles and pours again.

It could be violence and nonviolence

it could be white and black women and men

it could be war and peace or any

binary system, love and hate, enemy, friend.

Yes and no, be and not-be, what we do and what we don’t do.On a corner in East Harlem

garbage, reading, a deep smile, rape,

forgetfulness, a hot street of murder,

misery, withered hope,

a man keeps pouring grape into ORANGE

and orange into the one marked GRAPE,

pouring orange into GRAPE and grape into ORANGE forever.

Rukeyser’s overt educational intention here may evoke a reflex uneasiness among some poetry lovers. When a work of art aims directly at “the public welfare,” the first objection concerns the proper motive of art. What is it art for? Beauty or truth? Entertainment or character building? Is Painting X worth looking at because of its subtle color, its ugliness, its idealism, its truth-telling, or because of its conversation with the history of aesthetics? Is the essence of art the unique expression of individuality, or of a cultural condition? When art is evaluated or loved for its “utility,” its ethical benefits, artists and intellectuals object that it has been demeaned, commodified, and oversimplified. The civic bureaucracy, meanwhile, argues that art is just not verifiable enough in its beneficence. But if we said that elementary-school playgrounds, with their monkey bars and swing sets, were intended to build hand–eye coordination and balance, would that make playgrounds oppressive, or less fun?

Rukeyser’s poem delivers its crucial idea in brief and forceful form, and although poems need no motive of instruction to justify themselves, hers accomplishes its mission memorably. The American who has read it will never take as given the duplicitous, inaccurate language that surrounds us commercially and politically in the way that Rukeyser’s speaker does. She urges us instead to see the corruption of language as it should be seen: as an ethical betrayal, as nothing less than an existential insult, one with snowballing consequences. Orange for grape, grape for orange — such a commonplace misrepresentation may seem trivial alongside fibs about weapons of mass destruction, yet it can lead into the valleys and mountains of bad faith. “The Ballad of Orange and Grape” provides anyone who has encountered it with a correlative, a reference point by which to recognize how certain worldly forces (in this case, indifference) anesthetize our language and thereby steal our reality.

Obviously, poems in a curriculum may usefully complicate and contradict one another. “The Ballad of Orange and Grape” addresses the ethics of language and the need for trustworthy speech. Against Rukeyser’s urgent formulation of that truth, one might, in our imaginary curriculum, counterpose Walt Whitman’s “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer,” which asserts the superiority of silence and nature to scholarly language and ideas. In Whitman’s poem, two kinds of learning are opposed to each other, and the speaker advocates playing hooky:

When I heard the learn’d astronomer;

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me;

When I was shown the charts and the diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them;

When I, sitting, heard the astronomer, where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon, unaccountable, I became tired and sick;

Till rising and gliding out, I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

“When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer” represents a streak of anti-intellectualism that is a familiar part of the American tradition of self-sufficiency and independence. The natural man, claims the poem, has little need for arid recitations of classroom knowledge. Rather, as Emerson suggested, it is the true work of each American to go outside and forge her own original relationship with the universe. Whitman’s lyric embodies that American narrative.

Is it so hard to believe that only twenty poems, commonly possessed and mutually valued, could make a difference in American culture? Our skepticism is founded in our ingrained impression of poetry as anemic, difficult, and obscure. We believe that, like other kinds of “high” art, poems must be force-fed to people; that poems are prissy, refined, cerebral, rhymed; that they are a kind of test devised to separate the bumpkins from the aesthetes. At bottom, such a prejudice, pervasive as it is, imagines that culture is a side dish on the meal of economic realism, an innocuous auxiliary to our lives.

To underestimate the appeal of art is to underestimate not only poetry but also human nature. Our hunger for myth, story, and design is very deep. I hold these poems’ truths to be self-evident. If we are not in love with poems, the problem may be that we are not teaching the right poems. Yet ignorance of and wariness about art gets passed on virally, from teacher to student. After a few generations of such exile, poetry will come to be viewed as a stuffy neighborhood of large houses with locked doors, where no one wants to spend any time.

POEMS DEFUSE SEXUAL ANXIETY AND ACKNOWLEDGE THE NATURALNESS OF CURIOSITY

Sharon Olds’s “Topography” could perhaps shatter the petrified classroom notion that poetry has no libido or sense of humor. The poem’s narrative achievement is to be both playful and wholesome on the subject of sex. “Topography” is also a tutorial in the pleasures of extended metaphor and language itself, allowed as it is to somersault in a non-directive, extracurricular capacity.

After we flew across the country we

got into bed, laid our bodies

delicately together, like maps laid

face to face, East to West, my

San Francisco against your New York, your

Fire Island against my Sonoma, my

New Orleans deep in your Texas, your Idaho

bright on my Great Lakes, my Kansas

burning against your Kansas your Kansas

burning against my Kansas, your Eastern

Standard Time pressing into my

Pacific Time, my Mountain Time

beating against your Central Time, your

sun rising swiftly from the right my

sun rising swiftly from the left your

moon rising slowly from the left my

moon rising slowly from the right until

all four bodies of the sky

burn above us, sealing us together,

all our cities twin cities,

all our states united, one

nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

The former U.S. poet laureate Robert Pinsky once said that American poetry would be a warmer, more inviting place if it included more sex, humor, and violence — if, in some ways, it artfully incorporated some of the “life-affirming vulgarity” of the popular entertainment that has, it sometimes seems, elbowed it aside. Olds’s poem dispels the atmosphere of stodginess and elitism we culture lovers must constantly resist. It also sets the table for a host of subsidiary conversations on subjects ranging from patriotism to porn, from the curious pleasure of phonemes (“Sonoma”) to the nature of innuendo (“Fire Island”). The god of play is Eros, and sometimes art leads with the libido. If Americans only knew that poetry is sexy, surely more books would be checked out of the library. “Topography” demonstrates one of the wondrous facts of American poetry — its populist brilliance and range. It can be high and low, entertaining, erudite, provocative, rude, brainy, and mysterious.

POEMS ACKNOWLEDGE TROUBLE AHEAD

Gender is such an inextricable part of our lives and our identities that we spend our lives trying to untangle its truths and mysteries. The literature of gender is vast because the struggle to understand it is a fundamental one; yet the incisive swiftness of poetry cuts to the heart of most subjects, including this one. Whereas “Topography” praises the united states of sex, the inevitable difficulties between male and female are addressed more seriously in “A Man and a Woman,” by Alan Feldman. In fierce, fast-moving, broken-off lines, the poem catalogues the passionate suspicions and doubts of each gender towards the other. Feldman’s poem opens door after door for discussion, and closes none of them:

Between a man and a woman

The anger is greater, for each man would like to sleep

In the arms of each woman who would like to sleep

In the arms of each man, if she trusted him not to be

Schizophrenic, if he trusted her not to be

A hypochondriac, if she trusted him not to leave her

Too soon, if he trusted her not to hold him

Too long, and often women stare at the word men

As it lives in the word women, as if each woman

Carried a man inside her and a woe, and has

Crying fits that last for days, not like the crying

Of a man, which lasts a few seconds, and rips the throat

Like a claw — but because the pain differs

Much as the shape of the body, the woman takes

The suffering of the man for selfishness, the man

The woman’s pain for helplessness, the woman’s lack of it

For hardness, the man’s tenderness for deception,

The woman’s lack of acceptance, an act of contempt,

Which is really fear, the man’s fear for fickleness,

Yet cars come off the bridge in rivers of light,

Each holding a man and a woman.

The difficulties and differences are immense — “Yet cars come off the bridge in rivers of light/ each holding a man and a woman.” Feldman’s poem is tough, true, and vivid enough to deserve registration in our communal anthology. It begins, artfully, with a declared but never explicitly answered question. The anger between the man and the woman is “greater” than what? Love? Greater than the other sorts of anger we feel? The way this opening grammar hangs, semantically incomplete, is one of the poem’s many charms and sophistications. The catalogue of gendered differences, clearly compiled from experience in the field, is a provocative pleasure of its own. It is not hard to imagine the difference this poem might make in helping a husband and wife to consider the reasons for tolerance.

POEMS REHEARSE THE FUTURE

Poems, some more than others, are songs, passed down through time. It is amazing how far and how long they can travel and still remain fresh. Was there ever a poet named Speaks-Fluently? That is the name assigned to the author of this Native-American poem of Osage origin, passed on to me by another poet. “Song of Speaks-Fluently” is as light as a nursery rhyme and as serious as a gospel; wry, yet firm about the facts of life. And what a flavor of reliability it bears from its at once distant and personal source.

To have to carry your own corn far —

who likes it?

To follow the black bear through the thicket —

who likes it?

To hunt without profit, to return without anything —

who likes it?

You have to carry your own corn far.

You have to follow the black bear.

You have to hunt without profit.

If not, what will you tell the little ones? What

will you speak of?

For it is bad not to use the talk which God has sent us.

I am Speaks-Fluently. Of all the groups of symbols,

I am a symbol by myself.

Here is the news, says the poem sympathetically: You too shall labor, and on Tuesday your enterprise shall not succeed, and on Wednesday you shall bend again to the labor before you. Now, this is a message well worth inclusion in the speech of any high school valedictorian in America. Instead of demanding favors of the universe, Speaks-Fluently tells us, we must cultivate the wisdom of the shrug and exercise the muscle of persistence. “You have to carry your own corn far. You have to hunt without profit.”

With its images of ancient farming and hunting, “Song of Speaks-Fluently” carries another quiet implication — that we readers, whatever our work, are connected to the oldest rhythms of human effort and human survival. The necessities and hazards of our lives have changed in appearance, but not in essence.

A thousand kinds of poems exist, and they point in an infinite number of directions.

POEMS TEACH AESTHETICS THAT ARE OF BROAD APPLICATION

Another dividend of even a basic investment in poetry is the way it refines our sensitivity for tone, for subtleties of inflection, which in turn enables us to navigate the world more skillfully. Take the delicate, tentative mix of irony and affection in “The Geraniums,” by Genevieve Taggard:

Even if the geraniums are artificial

Just the same,

In the rear of the Italian café

Under the nimbus of electric light

They are red; no less red

For how they were made. Above

The mirror and the napkins

In the little white pots . . .

. . . In the semi-clean cafe

Where they have good

Lasagna . . . The red is a wonderful joy

Really, and so are the people

Who like and ignore it. In this place

They also have good bread.

Taggard’s poem, delivered in a reflective, tender, meditative voice, is about aesthetics. It asks an interesting question: Can a thing be simultaneously false and beautiful? Is the modern world, with its manifold illusions, nonetheless an environment in which the soul can find nourishment? What do we see and what do we habitually ignore? Can we train ourselves to appreciate any environment? Consider the loveliness of the humble fake flowers! To cultivate an ear for tone is, oddly enough, to cultivate one’s own perceptual alertness. In “The Geraniums,” irony and wonder (the “semi-clean” cafe and the “wonderful joy, really” of red) collaborate intricately in the speaker’s casually unfolding voice. To develop an ear for such delicate modulations is in fact a survival skill that can aid one for a lifetime.

The Fatal Card: The powerful drama, by Haddon Chambers & B. C. Stephenson. Library of Congress, Cabinet of American Illustration collection

I could go on with more examples. My list is ready — I am only waiting for the president to give me the go-ahead. Perhaps twenty other experienced readers of poetry might come up with twenty other lists of poems that might similarly serve, poems that could be smuggled into twenty-first-century life as amulets and beatitudes to guide, map, empower, and console. The argument of this essay is not complex; the poems are richly so.

Poems build our capacity for imaginative thinking, create a tolerance for ambiguity, and foster an appreciation for the role of the unknown in human life. From such compact structures of language, from so few poems, so much can be reinforced that is currently at risk in our culture. As an American writer, I long for the art form to be restored to its position in culture, one of relevance and utility, to do what it can. In everything we have to understand, poems can help.

To implement a program of poetry reading and appreciation across the educational system, in prep schools and charter schools as well as in public schools, would take daring and conviction and willingness. It would take the willingness of teachers to enjoy poems themselves, to handle a kind of material that aims not to quantify, define, or test but to open one door after another down a long hallway. To communicate credulity requires credulity, the faith that a small good thing contains the potential for great transformations. Yet our own lives provide the testimony that futures are formed from such chance encounters, such small receptions and affections. In increment after increment, the grace of the future depends on the preparation and generosity of the past. It is that incidental, almost accidental, encounter with memorable beauty or knowledge — that news that comes from poetry — that enables us, as the poem by William Stafford says, to think hard for us all.

TONY HOAGLAND’S TWENTY POEMS

Twenty-First. Night. Monday., by Anna Akhmatova

God’s Justice, by Anne Carson

memory, by Lucille Clifton

A Man and a Woman, by Alan Feldman

America, by Allen Ginsberg

Bamboo and a Bird, by Linda Gregg

A Sick Child, by Randall Jarrell

Black People & White People Were Said, by Kerry Johannsen

Topography, by Sharon Olds

Wild Geese, by Mary Oliver

Written in Pencil in the Sealed Railway-Car, by Dan Pagis

Merengue, by Mary Ruefle

Ballad of Orange and Grape, by Muriel Rukeyser

Waiting for Icarus, by Muriel Rukeyser

American Classic, by Louis Simpson

The Geraniums, by Genevieve Taggard

Song of Speaks-Fluently, by Speaks-Fluently

Traveling Through The Dark, by William Stafford

When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer, by Walt Whitman

Our Dust, by C. D. Wright