Spotlighting the Surveillance Court

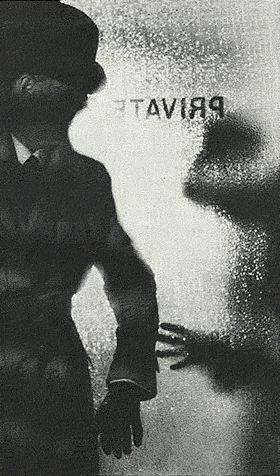

Why has a secret court been permitted to place America at the center of a new global panopticon?

The term “Roberts Court” is used, in keeping with long-established convention, to describe the Supreme Court in the period after John Roberts was installed as Chief Justice at the end of September 2005. But the designation might apply more fittingly to a secretive and increasingly powerful judicial institution that has been thrown into the spotlight by a series of recent disclosures: the court established by the 1978 Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), whose judges Roberts has since his ascension in 2005 been responsible for selecting. Indeed, some of the most disturbing of the recent disclosures concerning National Security Agency programs came in the form of FISA court decisions filled with statutory citations and footnotes — decisions that would have been highly controversial at the time they were rendered, had that not been done in total secrecy.

In a significant piece of analysis in the New York Times, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Eric Lichtblau finds that

In more than a dozen classified rulings, the nation’s surveillance court has created a secret body of law giving the National Security Agency the power to amass vast collections of data on Americans while pursuing not only terrorism suspects, but also people possibly involved in nuclear proliferation, espionage and cyberattacks, officials say. The rulings, some nearly 100 pages long, reveal that the court has taken on a much more expansive role by regularly assessing broad constitutional questions and establishing important judicial precedents, with almost no public scrutiny, according to current and former officials familiar with the court’s classified decisions.

In the Wall Street Journal, Jennifer Valentino-DeVries and Siobhan Gorman present an analysis similar in many respects to Lichtblau’s. They focus on one of the curiously weak pretexts used by the court to get around the restrictions placed on it by FISA and the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution:

[C]urrent and former administration and congressional officials are shedding new light on the history of the NSA program and the secret legal theory underpinning it. The court’s interpretation of the word enabled the government, under the Patriot Act, to collect the phone records of the majority of Americans, including phone numbers people dialed and where they were calling from, as part of a continuing investigation into international terrorism.

“Relevant” has long been a broad standard, but the way the court is interpreting it, to mean, in effect, “everything,” is new, says Mark Eckenwiler, a senior counsel at Perkins Coie LLP who, until December, was the Justice Department’s primary authority on federal criminal surveillance law. “I think it’s a stretch” of previous federal legal interpretations, says Mr. Eckenwiler, who hasn’t seen the secret ruling. If a federal attorney “served a grand-jury subpoena for such a broad class of records in a criminal investigation, he or she would be laughed out of court.”

On December 20, 2005, Judge James Robertson sent a letter to Chief Justice Roberts announcing his resignation from the FISA court. Robertson was easily the best known and most highly regarded of the eleven judges on the court at the time. His letter provided no explanations, but did trigger speculation in the media that he was troubled by the court’s activities and did not wish to be associated with them. Following the NSA disclosures, it has suddenly become clear why Robertson resigned. Indeed, testifying before the Federal Intelligence Oversight Board on Tuesday, he finally spelled out his concerns, saying, “Anyone who has been a judge will tell you a judge needs to hear both sides of a case.” He also asked whether the FISA court should be offering legal approval for surveillance programs, saying it “has turned into something like an administrative agency.”

In the absence of published opinions that present the facts of cases and the legal reasoning applied to their rulings, it is very difficult to form judgments about the performance and attitudes of the FISA court. Nevertheless, the crumbs that have fallen from the table raise profound questions about the integrity of the court and the legitimacy of its rulings.

There are three obvious ways the court might be salvaged. The process has to start with a new selection process for judges. It will not do to have a court shaped entirely in the image of John Roberts. A review of the current bench leaves no doubt that he has applied his own movement-conservative notions about national-security policy as a litmus test, picking judges who can be counted on to give a wide berth to the intelligence community’s push to radically expand its information bases by reaching into the communications of billions of people around the world.

To restore its credibility, the court will require judges who are representative of the federal judiciary as a whole, with appropriate balance between Democratic and Republican nominees, diverse personal and ethnic backgrounds, broad regional representation, and differing attitudes toward civil liberties and national security. Most importantly, FISA judges need to be figures of demonstrated independence, who are unlikely to be steamrolled by prosecutors arguing for extraordinary powers.

Second, the FISA court should include a special court officer (with high-level security clearance) whose duty is to aggressively advocate the public interest by zealously enforcing Fourth Amendment rights and working to ensure that remedies proposed by the government are drawn as narrowly as they could be. The American legal system operates on a principle of adversarial justice; it functions weakly when only one side gets to make an argument with no push back from its opponent. The current system of ex parte review grates against this tradition. The FISA court is surely encountering cases in which adversaries should have notice and an opportunity to make arguments, even if security classifications limit complete access to the file. Orin Kerr has recently called for an “oversight section” within the Justice Department that could play such a role, and his proposal strikes me as both modest and reasonable.

Finally, in reviewing the classified decisions that have now been leaked, it seems clear to me that the extreme secrecy applied to the court’s decisions needs to be reassessed — particularly given that many of those decisions are now out in the open. In the American legal system, the decisions of federal judges constitute an important form of law. The notion that vast expanses of an increasingly important area of law should be entirely out of the public domain is troubling. It should be possible to redact the opinions so that highly classified material is excluded, but the rules of decision announced by the court are available to all. The judges of the FISA court may have reason to be embarrassed about some of their decisions, but that is no excuse for keeping them hidden from the public.

The FISA court has been laying the foundation for America to sit at the center of a new global panopticon. It is bizarre to see what should be a legislative function usurped by a group of nominally conservative judges who have been permitted to work entirely in the dark. The only antidote to the court’s power may be to give the public more insight into its dealings and decisions. Americans shouldn’t have to rely on episodic leaks; real reform is necessary.