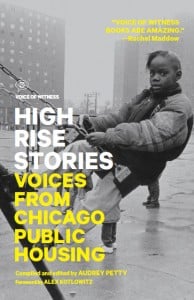

High Rise Stories

Audrey Petty on the history of Chicago public housing, the intimacy of oral histories, and reconstructing demolished communities

In 2011, the last remaining tower at Cabrini-Green Homes, the most notorious of Chicago’s public-housing projects, was dismantled by crane and wrecking ball. The city breathed a collective sigh of relief, and the Chicago Housing Authority shifted its focus to building mixed-income developments as part of its plan for reform. Around the same time, writer Audrey Petty began to speak to the displaced residents of Cabrini-Green and nine other public-housing developments, recording their memories of lives spent in places Chicago wished to erase. She collected twelve of these interviews in the book High Rise Stories, recently released as part of the Voice of Witness series from McSweeney’s. I spoke with Petty and asked her six questions about the interviews, the people she met, and how the process changed her.

1. As a native Chicagoan, were you personally invested in collecting these stories, and did the project change how you identify with the city?

Growing up on Chicago’s South Side, communities like the Robert Taylor Homes, Stateway Gardens, and Ida B. Wells were on my routes to other places: to piano lessons, Comiskey Park, my relatives’ houses, or downtown. As a child I was interested in the developments, and I also intuited that they were very separate from me; they were unto themselves. When I was very young, maybe seven or eight, there was a kid who lived in the Robert Taylor Homes who hung out with all the kids on my block. I never imagined I would go to his house; it never occurred to me that I would or I could. That weird tension was a big part of my consciousness.

As I came of age in the 1970s and 1980s, I learned through the media about the tragic and violent events that occurred in public-housing high-rises, which forged a distinct connection to those addresses. I felt equal measures curiosity and fear. When the buildings did come down, decades later, I felt their absence as a loss. I wanted to get closer to them somehow.

Three years after beginning the project, I feel more connected to the city. I see more patterns in Chicago’s history, and in things that are going on here now. And I’m more interested in the ground where I stand. Having grown up in a townhouse in Hyde Park, I kind of took my own home for granted. I didn’t think much about what existed before that house stood in that place. On the heels of my work in High Rise Stories, I’m starting to learn more about the history of my block, of my neighborhood. My childhood home was the product of someone’s else’s home being cleared out. All of this has become electric to me.

2. Why did you choose to interview only former residents of public-housing developments, as opposed to people who were involved from other angles, such as employees of the Chicago Housing Authority or private-housing residents?

From the very start, I was determined that this book should exclusively feature the voices of residents. I was interested in talking to people who could reconstruct the places from the inside. Even though there’s a bigger picture here, involving complex relationships between other bodies, entities, and institutions, residents held an authority no one else did. I wanted to read their voices — not only what they said, but how they said it.

“Not too long after my son got killed, must have been in the fall of ’91, I was at a benefit dinner, something to do with my community work, and this reporter came up to me and said, ‘Aren’t you Ms. Wilson?’ When I said that I was, he said, ‘Aren’t you afraid of living in Cabrini with all this shooting and stuff?’ I said, ‘No. I even leave out at night and go to the store,’ which I did. I said, ‘Only time I’m afraid is when I’m outside of the community. In Cabrini, I’m just not afraid.’ It’s like I told my boss, ‘If I’m going to live somewhere all these years and be scared, I’m crazy.’ ”

—Dolores Wilson

3. Ben Austen’s story “The Last Tower,” in the May 2012 issue of Harper’s, emphasizes the strong sense of community experienced by public-housing residents and their mixed feelings about Cabrini-Green’s demolition, even as the event was trumpeted as progress. In High Rise Stories residents express similar sentiments. In what ways were their experiences positive?

When I started interviewing people, the way in for me initially was to start with questions like, “Talk about your apartment: What do you remember about it? What was the layout? Did you know your neighbors?” I hoped the answers would lead to more questions, but I wasn’t prepared for the deep complexity of what people shared, or the powerful mix of conflicting emotions they felt when they talked about their homes and their communities. One woman said, without sarcasm or bitterness, “I saw shootings, I saw people killed — but other than that it was lovely.” All of these emotions were possible simultaneously, and one didn’t cancel out the other.

Many people shared very positive memories with me of the hospitality and conviviality they enjoyed on their floors and in their buildings. As Chandra Bell, one of the narrators, put it, “All your kids play together. That’s when you become a big family. One of us might get a job and be like, ‘Hey neighbor, can you watch my kid?’ That’s how it went, and it was real nice.”

4. Do you see these narratives continuing in the tradition of the oral-history projects of Studs Terkel, the Works Progress Administration, and today’s Storycorps? Why do you think the simple act of listening and recording might resonate more powerfully than a conventional journalistic account?

I most definitely think High Rise Stories continues in those traditions. I’m an avid Storycorps listener and always find myself amazed by what can be conveyed about a person through a three- or four-minute conversation — how a story can bring me to laughter or tears or discovery or surprise just that quickly. I also read Studs Terkel as I was aspiring to be a writer; he was a quintessential Chicagoan, and his passion and avidity inspired me. And I’d studied the WPA slave narratives in college and was bowled over by them. What lends oral history such power, I think, is its immediacy, and the intimacy that is forged between a speaker and a listener when the storyteller offers some personal truth that matters to them.

5. How do these individual narratives fit into the larger historical narrative of Chicago?

The story of public housing is the city’s story. Where and how it was and wasn’t built in the 1950s and 1960s communicates a great deal about racial and class segregation here. In the modern era, black people were often cordoned off or hemmed in, whether through redlining or restrictive covenants. In the 1940s, when veterans were returning from the war, black veterans were kept out of subsidized housing where white people lived. There were riots — a great deal of violence was inflicted on black people — to maintain the segregation of this type of public housing. In the late 1960s, when Martin Luther King, Jr. turned his efforts to the issue of lack of equal access to fair and decent housing, he moved with his family to Chicago’s West Side to raise awareness. When I was a kid in the 1970s, I didn’t know the term “white flight,” but I saw it firsthand, all over the city. Public housing was and still is populated by people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, but the mega-developments were built in black neighborhoods, and this was not coincidental.

The impetus for the book was the Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation. After several decades of defunding, the developments were to be dismantled, and the conventional understanding was that this was a good thing, that this was reform. But when a system this big fails, it’s important to consider how and why it did. The reflex for many — “Let’s be done with this” — does a disservice to the truth that these were communities. Even now, in this moment, there are people who were displaced who have nowhere to live, and people who live under harsher conditions managed by the private sector. I hope this book communicates that the story is more complicated than people outside these communities understand, and that it’s not over.

6. Alex Kotlowitz writes in the book’s introduction, “With public housing gone, in some quarters there’s a notion that everyone’s made it, that poverty has gone out of fashion.” The Plan for Transformation’s demolition of public-housing high-rises has erased these formerly very visible towers from the landscape, and to some extent the people who lived there. What does the future hold for former CHA residents?

The answer is as wide as the city limits. Most of the people I met rent in the city, in private-sector housing. Dolores Wilson moved to Dearborn Homes, the first public-housing development built in the city after World War II. She’s active in her local residents’ council and on good terms with her neighbors, but she still returns to her home church back in her old neighborhood every Sunday. One of the narrators of High Rise Stories is homeless. He has lived in several halfway homes and his current situation is quite precarious. Another narrator was homeless when we met for our first interviews, but is now gainfully employed, engaged to be married, and living in a suburb.

The answer is as wide as the city limits. Most of the people I met rent in the city, in private-sector housing. Dolores Wilson moved to Dearborn Homes, the first public-housing development built in the city after World War II. She’s active in her local residents’ council and on good terms with her neighbors, but she still returns to her home church back in her old neighborhood every Sunday. One of the narrators of High Rise Stories is homeless. He has lived in several halfway homes and his current situation is quite precarious. Another narrator was homeless when we met for our first interviews, but is now gainfully employed, engaged to be married, and living in a suburb.

Two narrators live in new developments — mixed-income properties built as part of the Plan for Transformation. Another narrator, who rents on the South Side, plans to leave the city with her children after finishing college. I wanted High Rise Stories to not only document what was lost but to testify to what remains, positive and negative, and to the narrators’ resilience: the ways that these people took care of themselves, and the bonds between them that still exist with the buildings gone. Even separated by many miles, former residents remain connected through churches, schools, Facebook, and a yearly reunion picnic near where they once lived. They’re also bonded by experience, by memory and story.