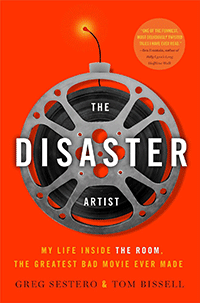

The Disaster Artist

Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell on life inside The Room, the greatest bad movie ever made

From 2003 to 2008, the vampiric face of filmmaker Tommy Wiseau hung over L.A.’s Highland Avenue on a billboard advertising his box-office failure, The Room. The movie, dubbed “the Citizen Kane of bad movies” in Entertainment Weekly, eventually acquired a cult following akin to the one surrounding The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Watching The Room is a surreal experience in antifilm, all but ignoring the conventions and evolution of the medium. Its dialogue is marked by non sequitur, its camera angles are awkward, and its plot, bizarre — all of which combine to lend the audience little sense of character motivation or visual and narrative consistency. As a disaster, though, it’s hard to look away from, which is to say that it’s a bad enough movie to be good.

In 1998 Greg Sestero met Wiseau, the film’s director, writer, star, producer, distributor, and executive producer, in an acting class in San Francisco. As a nineteen-year-old apprentice, Sestero was taken with Wiseau’s fearless displays of bad acting, as well as his striking appearance and unidentifiable accent, which sounded like something between French and Austrian. The two became scene partners and developed a strange friendship, for a while sharing a one-bedroom apartment in Los Angeles as Sestero struggled with his fledgling acting career and Wiseau penned the screenplay for The Room. When production began, Sestero was cast as Mark, the best friend of the main character, Johnny (played by Wiseau); the pair are caught in a love triangle with Johnny’s fiancée.

Sestero met Harper’s Magazine contributing editor Tom Bissell while Bissell was conducting research for his article “Cinema Crudité: The mysterious appeal of the post-camp cult film,” which appeared in the August 2010 issue. The Disaster Artist, co-written by Sestero and Bissell, recounts Sestero’s experience acting in The Room and his complicated relationship with Wiseau. The book gives a humorous yet sincere peek into the creation and creator of The Room. I asked Sestero and Bissell six questions that were tearing me apart, and they kindly took their responses out of their pockets:

1. The Disaster Artist, like The Room, lies somewhere between romantic drama and dark comedy. How did you go about capturing this mood?

Greg Sestero: The Disaster Artist is a character and “unlikely friendship” story first, and a chronicle about making a famously unsuccessful movie called The Room second. I wanted readers who’d never seen The Room to feel like they could still get lost in the story.

Tom Bissell: The Room is like a funhouse-mirror version of a conventional movie. By writing our story as a series of alternating, timeline-swapping chapters, I really hoped we could replicate that feeling of walking into a series of utterly mysterious hallways in which you’re never quite sure what’s going on. We tried to time the revelations in the book to play off each other, so that, just as Tommy seems the most bananas during the making-of sections, we clobber you with something really sad (and sympathy-generating) from his and Greg’s past. We wanted it to be funny and tragic, which is what The Room also is.

“Maybe I’d learn some of [Tommy’s] fearlessness. What made him so confident? I was desperately curious to discover that. It wasn’t his acting, obviously, which was extraordinarily bad. He was simply magically uninhibited; the only person in our class — or any class I’d ever taken, for that matter — whom I actually looked forward to watching perform. The rest of us were toying with chemistry sets and he was lighting the lab on fire.”

2. Tommy Wiseau might be the most eccentric person in the world. In the book, you let Wiseau do all the work to show this, but you manage to redeem him through Greg’s strange admiration for Tommy and writing that encourages a sort of guilty laughter in the reader. How did you handle dealing with Wiseau as a character while writing the book?

GS: I wanted to do full justice to Tommy’s hilarity and wackiness. He is such a fascinating character, with so many signature lines and laugh-out loud moments. No one sees the world like he does. No one. Letting him speak for himself, as himself, as best as I could remember it all, was the best way to “write” Tommy.

TB: Greg’s right. With Tommy, you barely even have to write the guy. He just is who he is. That’s his charm and that’s his magic. Report merely what he says and what he does, and you’re already 85 percent of the way there. I agree with you, by the way: Tommy might indeed be the most eccentric — and fascinating — person in the world. Certainly he’s the most fascinating person I’ve ever written about. There is quite literally no one else like him. His singularity makes The Room what it is.

3. Greg’s voice is evident throughout the book, and Tom’s prose style also crops up here and there. How was the co-writing experience?

GS: Working with Tom was great. After reading “Cinema Crudité,” I knew he was the ideal co-writer for The Disaster Artist. My goal with the book was to delve more into the emotionally confounding and inspiring aspects of Tommy and The Room. “Write something first rate about something fifth rate” — that was our motto while we worked on the book.

TB: Greg had to lean on me pretty hard to write the book with him, because I was teaching and had another book I was writing and was working on video-game stuff — too much! I just had way too much to do. But the more I talked to Greg about the story and his experiences with Tommy, the more I realized he was sitting on something potentially great. Capital-G great. This was born out when we actually started recording tape and getting the stories down, after which I turned our transcripts into chapters. Greg then thoroughly rewrote those chapters and brought them more into line with his memories and impressions. Then I rewrote, and he rewrote, and so on. We rewrote each other so much that I barely even remember whose lines are whose anymore. What I love about the book is how Greg’s and my voices sort of blend into a kind of third consciousness. It’s not quite fully him and it’s not quite fully me. It’s both of us, unified by this crazy artifact of American culture.

4. Tom, did either your fiction or your nonfiction tend to inform this book one more than the other?

TB: I said to Greg when I was looking around for a co-writer for him, before I agreed to be that co-writer, “You’re going to need a fiction writer to do this story justice.” Tommy’s texture is that of a fictional character. He’s Jay Gatsby meets Orson Welles meets a Martian diplomat meets Norma Desmond meets Tom Ripley meets God-only-knows. A straight non-fictional representation of him would be interesting, because he’s so interesting, but I feel like Greg’s memories of Tommy could not be properly inhabited without approaching those memories as a fiction writer. Norman Mailer and Truman Capote both wrote true-life novels, and Mailer said just because something’s true doesn’t mean it’s not a novel. I really like that. The Disaster Artist, which is a true story, is probably the closest thing to a full-blown novel I’m ever going to write, or co-write. And I feel like I can say this because it’s more Greg’s book than mine: I’m pretty sure I’m incapable of writing a novel that’s better, or crazier, than The Disaster Artist.

5. Greg, you tell us what you know about Wiseau in the book, but we’re left feeling that no one is exactly certain where he came from or how he found $6 million to fund the movie. Between your own coming-of-age story and Wiseau’s biography, which slowly unfolds across the book, much of The Disaster Artist is about identity. You write that the behind-the-scenes footage was even stranger than the movie. Among the highlights was an impromptu meeting on the first anniversary of 9/11, during which Wiseau demanded five minutes of silence before launching into a tirade about America being the best country in the world then leading his crew in a chant of “U-S-A! U-S-A!” There was also a stage fight between you and Wiseau that turned real and was subsequently used in the film and a scene in which Wiseau loomed over you creepily while you shaved your beard, saying, “Slow down. Don’t cut it. Don’t cut.” What was it like to witness and reconstruct the person you were while filming The Room?

GS: My experiences making The Room were hilarious and crazy. Tom and I filled up an entire flash drive with audio interviews. It was also really great to interview the cast and crew, who were very supportive, and who filled in many bits of detail and dialogue that I’d forgotten. Also, Tommy invited me on tour with him while I wrote the book, which helped me get his perspective on the film’s success, and to get to know him in a different way. Our best source, though, might have been the behind-the-scenes footage. For clothes, times of day, dialogue, and all those details, that footage was a gold mine. Tom and I spent hours watching it all up in Michigan a couple winters ago. I don’t think Tom’s mouth closed for several hours.

TB: I was, indeed, shell-shocked by the experience. The-Room-the-movie is, as we all know, incredible. The-Room-the-behind-the-scenes-footage is an entirely other experience. Never seen anything like it. My God someone could make an incredible documentary about the movie with that footage alone.

TB: I was, indeed, shell-shocked by the experience. The-Room-the-movie is, as we all know, incredible. The-Room-the-behind-the-scenes-footage is an entirely other experience. Never seen anything like it. My God someone could make an incredible documentary about the movie with that footage alone.

6. Greg, are you still close with Wiseau?

GS: I’ve known Tommy for fifteen years. I think, when you’ve gone through such a unique experience with someone, like we have, you’ll always share a certain bond. A strong bond. Tommy has been supportive of the book and attended the L.A. book launch, which meant a lot.