Cutting School in Kansas

The state Supreme Court prepares to decide the fate of Kansas public-school funding

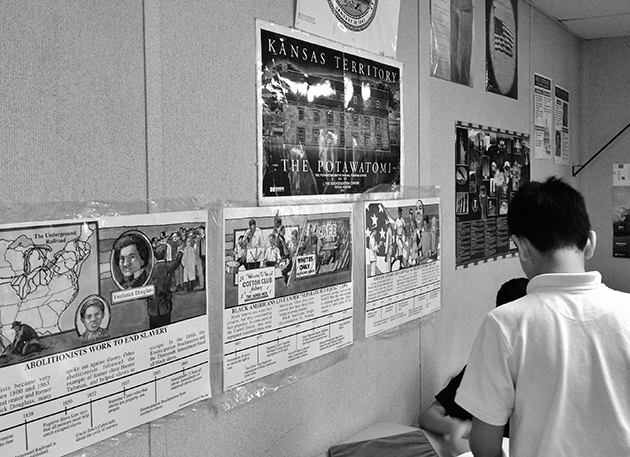

Kansas Day at a Title 1 school in Wyandotte County, which has the state’s highest poverty rate, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Kansas City, Kansas, January 29, 2014 © Sarah Smarsh

In his State of the State Address on January 15, Governor Sam Brownback declared that Kansas depends “not on Big Government but on a Big God that loves us and lives within us.” The sentiment likely got an amen from Koch Industries, the multibillion-dollar, Wichita-based conglomerate that bankrolls Brownback’s campaigns and profits handsomely from his breathtaking tax cuts. And it likely provoked a groan from public-school districts currently suing the state for underfunding public education. The decision on that case — due any day from the Kansas Supreme Court — has implications for eleven states, including California, New York and Texas, that are facing similar litigation.

During his address from the ornate, newly restored capitol in Topeka, Brownback warned the judicial branch to mind its own business. “On the number-one item in the state budget — education — the Constitution empowers the Legislature, the people’s representatives, to fund our schools,” he said, before hinting at the potentially destructive powers of the judiciary. “Let us resolve that our schools remain open and are not closed by the courts or anyone else.” Republican representatives sprang from their seats to applaud, apparently indignant that a court might dare hold them accountable to a law created by their own governmental body.

In the 1960s, Kansas legislators amended the state constitution to require “suitable provision for finance of the educational interests of the state.” Citing that language, a coalition of students and school districts sued the state in 1999; the case, Montoy v. Kansas, led to a 2005 state Supreme Court ruling that interpreted “suitable provision” as sufficient resources to accomplish schools’ required duties — meeting academic-achievement benchmarks, graduating students from high school, preparing them for state-college admissions standards. “We need look no further than the legislature’s own definition of suitable education,” the justices wrote, “to determine that the standard is not being met under the current financing formula.” So, they said, pay up.

In response, then governor Kathleen Sebelius called a special summer session, and within weeks the mostly conservative legislature passed a three-year plan to increase funding. But it wasn’t long before allocations slid again. The economy crashed just as Sebelius left to join the incoming Obama Administration, and her replacement, Mark Parkinson, a Democrat who had crossed the aisle to serve as her running mate in 2006, approved education cuts amid a budget crisis. Brownback’s election in 2010 led to the education budget’s veritable decimation. Between 2009 and 2012, Kansas public schools lost $511 million in state funding, and in 2012, Brownback signed off on $3.7 billion in cuts to the overall state budget across five years, a move he called “a real live experiment.”

A new coalition of schools sued the state in 2010, arguing that the legislature had failed to make good on the funding remedies pledged after Montoy. A district court ruled in their favor in January 2013, and an appeal sent the case, Gannon v. Kansas, to the state Supreme Court.

During arguments last October at the severe judicial building in downtown Topeka, the state’s lawyers started out by raising concerns about separation of powers, citing federal precedent protecting legislative activity from judicial authority. “If courts had power to declare a law unconstitutional, it would be ironic, given the courts in our country typically are the branch that is not elected, and not answerable to the people,” said lead appellate counsel Stephen McCallister (a bold statement to make in the city that gave rise to Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas). McCallister also argued that the cuts were pragmatic, not political. “The Great Recession came, and the revenues went in the tank. At times government has aspirations it then struggles to fulfill,” he said. “The same is true of the Kansas constitution, which is neither a suicide pact nor a bankruptcy pact.”

Justice Eric Rosen, a Sebelius appointee, wasn’t buying it. “It stands before me, in my eyes, as a broken promise,” he said. On the matter of separation of powers, Rosen said his court was enforcing existing law, and therefore within its purview. When the state’s arguments concluded, most of his fellow justices appeared similarly dubious. “If the people wanted to have schools,” said Justice Dan Biles, “presumably they wanted the schools to teach something.”

The presumption that schools are built to function has remained sturdy here since territorial settlers fashioned schoolhouses from sod. In stripping the resources that allow public schools to educate children, the current state administration — which has demonstrated its preference for privatization in nearly every budget column — perhaps reveals its desire to tear the public system down.

High-school biology teacher David Reber, a long-time member of the Kansas National Education Association and the chief negotiator for his local union in Lawrence, thinks so. For Reber, today’s funding battle is but one facet of a broad, hostile campaign: impossible testing standards, devised to make the public system appear ineffectual; the erosion of limits on local funding, which favors schools in wealthy districts; and curricular mandates that blur the line between church and state in biology and social-studies classrooms. (Reber critiques these forces on his website, which features, alongside photos of biological specimens and of himself onstage with his metal band, original song lyrics that would be at home on an album called Weird Al Goes Union. To the melody of Black Sabbath’s “War Pigs”: “School reformers — pompous asses / Tell us how to teach our classes / Profiteers they chart their courses / Fetishizing market forces.”)

Among the other measures Reber singles out is the legislature’s forbidding, in 2013, of the voluntary direct electronic transfer of paycheck funds to political action committees — an important support mechanism for unions in recent years. State lawmakers have also granted to any organization claiming to support teachers the rights to post materials on workroom bulletin boards and to email school districts — prerogatives that were formerly exclusive to unions, per state contract negotiations. The change, Reber says, means “the Koch brothers and their phony unions can come in and have twenty different organizations demanding a bulletin board.”

Kansas remains among the country’s highest-scoring states on the National Assessment of Educational Progress but has begun to slip by its own measures. A Department of Education report showed that proficiency rates dropped from 2012 to 2013, most notably in math, from 85 percent to 78 percent. Test scores also indicate widening gaps along racial and socioeconomic lines; the percentage of black fourth-graders who can’t read at a basic level has risen from 44 percent to 53 percent since 2009, the year the state began back-pedaling on school spending.

The futures of nearly half a million children sitting in Kansas public-school classrooms will soon be shaped by the state Supreme Court. If the justices side with the state and strike down the lower court’s ruling, the precedent they set might threaten funding gains won via litigation in other states. And if justices again side with the districts and require public-school funding to be restored, legislators may once again fail to comply. Reber expressed confidence that the court would uphold the previous decisions calling for budget increases. “I don’t know how they could do otherwise,” he said. “But there’s also little doubt in my mind that the legislature’s gonna say, ‘Oh yeah? Make us.’ ”

—

Sarah Smarsh has reported on Kansas’s culture, politics, and environment for more than a decade. She is the creator of Free State Media, a public audio-storytelling platform that will focus on Kansas education in Autumn 2014.