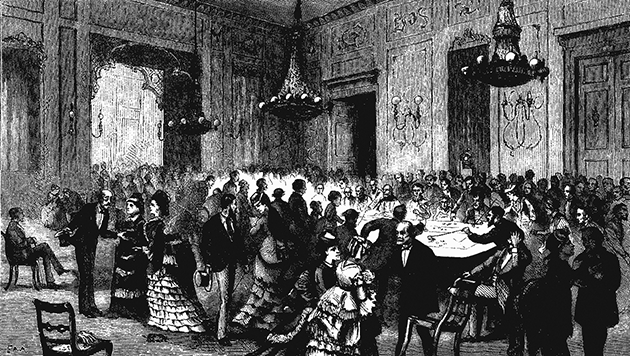

From Harper’s Magazine (June 1872)

In Dostoevsky’s The Gambler, a wealthy woman who is nearly dead joins her family at a casino vacation. Her goal is to lose her fortune. Her reason? She knows her family is waiting for her to die.

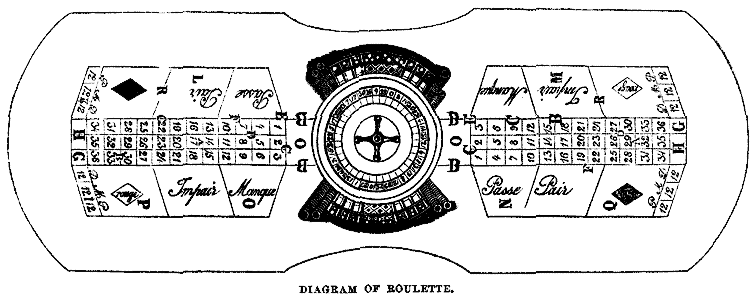

At the casino, she watches the roulette wheel. It comes up on zero, and she asks what “zero” means. The protagonist, Alexei Ivanovich, explains to her that zero means the house takes all the money on the board, unless someone has bet zero, in which case they get thirty-five times their bet. She tells him to stake one gold piece on zero. She loses and tells him to stake one gold piece on zero again. Three times, she loses.

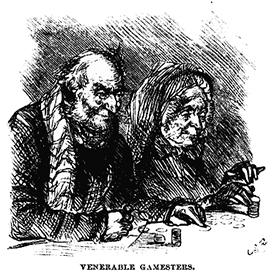

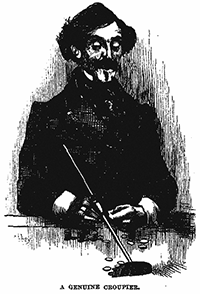

Upon this the Grandmother went perfectly crazy. She could no longer sit still, and actually struck the table with her fist when the croupier cried out, “Trente-six,” instead of the desiderated zero.

“To listen to him!” fumed the old lady. “When will that accursed zero ever turn up? I cannot breathe until I see it. I believe that that infernal croupier is PURPOSELY keeping it from turning up. Alexis Ivanovitch, stake TWO golden pieces this time. The moment we cease to stake, that cursed zero will come turning up, and we shall get nothing.”

He stakes two gold pieces, and the zero hits. She puts an obscene amount of money on zero. It does not hit. She tells Alexei to make the same bet. It hits. She moves her money to red. It hits. She makes a second equal bet on red — it hits. Alexei, as narrator, says, “I myself was at heart a gambler. At that moment I became acutely conscious both of that fact and of the fact that my hands and knees were shaking, and that the blood was beating in my brain.”

The old lady takes her winnings. She says, “Enough! Let us go home. Wheel my chair away.” The next day she comes back to the casino. She’s got a new lease on life, and she wants to win. She loses everything.

This was the way Dostoevsky gambled. Roulette was his game. He’d build his money on red, and then work zero. The thing about roulette, and gambling in general, is that it preys on the superstitious. Superstitious people regard their flashes — I should bet zero now — as somehow divine, or mystical. These little flashes, which occur before every bet or sat-out game, carry tremendous weight, whether they are ignored or heeded, however the game goes.

My husband and I were driving from Iowa City, where I am a second-year MFA candidate in fiction, to Kansas City, where he teaches philosophy, and where we have our home. We were making the drive Wednesday night, so that I could see my dentist on Thursday. I had tried to reschedule the appointment, but my dentist runs his clinic like a three-star restaurant. His receptionists are rude if you try to cancel. I’m not really sure what allows them to be that way — I mean, he is a fine dentist, but he’s nothing special. Perhaps it is the model sailboat in his waiting room. A sailboat, as any superstitious person knows, is auspicious, and brings money into a business.

My husband and I were driving from Iowa City, where I am a second-year MFA candidate in fiction, to Kansas City, where he teaches philosophy, and where we have our home. We were making the drive Wednesday night, so that I could see my dentist on Thursday. I had tried to reschedule the appointment, but my dentist runs his clinic like a three-star restaurant. His receptionists are rude if you try to cancel. I’m not really sure what allows them to be that way — I mean, he is a fine dentist, but he’s nothing special. Perhaps it is the model sailboat in his waiting room. A sailboat, as any superstitious person knows, is auspicious, and brings money into a business.

At Exit 33 of Interstate 35, I began to make hooting sounds. This was my way of saying I had spotted a McDonald’s and wanted a Diet Coke and a vanilla cone. My husband exited the highway. We were about a hundred feet from the stop sign when he said, “The car died.”

We walked through a field, over a fence, to a Taco Bell. We called the top-rated body shop in — “Where are we?” my husband asked the counter girl. She said, “Osceola.”

The man who answered wouldn’t take the job. He said it was likely a timing belt, and that he didn’t have ten hours to devote to it. He said, “I know a place that’d do it, but I almost hate to send you there. I knew Cory’s father.”

Fifteen minutes later, a young man hitched up our car, and we rode up front with him to a body shop. When we arrived, children ran in circles around it. Their mother said, “Stop running around the car!” and, “What’d I tell you about running around the car? Stop.”

Cory, the owner of the body shop, put us up for the night using his player’s card at the Lakeside Casino. He said, “It gives me a free night every week. I never use it. Sometimes we put somebody up if it’s a big job.” My husband and I each took out $100 of our own money in chips. We played a few hands of blackjack. It made me nervous. I said, “Let’s go.” We left $35 up. I felt like a coward, but I couldn’t take it.

Cory, the owner of the body shop, put us up for the night using his player’s card at the Lakeside Casino. He said, “It gives me a free night every week. I never use it. Sometimes we put somebody up if it’s a big job.” My husband and I each took out $100 of our own money in chips. We played a few hands of blackjack. It made me nervous. I said, “Let’s go.” We left $35 up. I felt like a coward, but I couldn’t take it.

In the middle of the night I woke up in a cold panic. I held my husband as tightly as I could. I was suddenly aware of how tenuous everything I have is.

In the morning I made a confession. I said, “You know, on our way to Iowa last week, I saw this casino as we passed it on the highway, and I wished we would stop here.”

“Amie!” he said, “This exact casino?” There are several casinos on the highway from Kansas City to Iowa City.

“Yup.”

“Oh, honey. What did you do?”

Superstitious people.

We went through ups and downs the next day. We were at $240, we were at $65, we clawed up to $135. I got an instinct and switched dealers — $400! $425! We were giddy. We kissed in the middle of the casino, and my method — praying for the man beside me to get rich — seemed like a divine secret. I told my husband, “Let’s walk around the casino a few times. I have to calm down.” I was shaking.

Confidently, we went to the craps table. I got on a hot streak. My husband wanted to make big bets, but I held him back. “I bet we’ll pay for the car!” he said. Even the ladies at the table wouldn’t let me walk away. I kept asking if I could, but I kept making more. “It’s like a cash register,” my husband said. We kept betting the field, $5 on each roll. The other man at the table was making big bets, and he made $1,100.

The funny thing about a hot streak is you can feel it. We both knew it was coming. We left the casino up. Back in the room we were so full of adrenaline we couldn’t watch movies. It was impossible to do anything. We went back to the casino.

The characters at the craps table looked ominous. They were smoking and drinking beer. At a glance it felt off. But we went up to it and — in less than three minutes — lost $400. With $75 left, we waited for the roulette table to open.

The characters at the craps table looked ominous. They were smoking and drinking beer. At a glance it felt off. But we went up to it and — in less than three minutes — lost $400. With $75 left, we waited for the roulette table to open.

I’d intended to work my way up on red, like Dostoevsky. But after three bets, I felt too revolted. I wanted it to end. I told my husband, “Take this and play the field on craps.”

He took our remaining chips and lay them down on the field. It hit!

“I can’t take that bet,” the lady running the table said. “I’m sorry, the dice were in the air when he put it down.”

“What do I do?” my husband asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Leave it. Let’s just end this.”

The man with the dice rolled again, and they dragged our chips away.

The cost of the timing belt was $873.46. We gave Cory $600 in $100 bills — that’s what the casino ATM delivered — and my husband sheepishly asked if he could write a check for the balance.