Is it finally time to let go of the Beatles? I feel strange even posing the question, having been born on the cusp of the glorious Sixties and formed, to an astonishing degree, by John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Oh, there was plenty of other stuff going on — Vietnam, LSD, black power, feminism, and the so-called sexual revolution, which Philip Larkin famously pegged to the 1963 release of Please Please Me. But what got etched into my brain, as if it were the surface of one of those malleable, lacquer-coated acetates, was that music. My father, a Toscanini fanatic who had actually sold his digestive juices as a medical student to pay for his first turntable, bought all the early records. When my parents had dinner guests, he would play them “Ask Me Why” to prove that the Beatles weren’t simply long-haired louts but could sing in tune and write something with those jazzy, sophisticated sevenths.

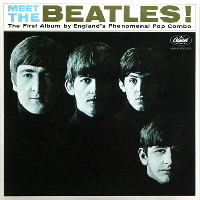

In the summer of 1965, when the band arrived in New York City for its second appearance at Shea Stadium, my mother cut a guitar silhouette out of cardboard and painstakingly made me a black wig out of coarse yarn. I had expected something more realistic — that would make me a dead ringer for Paul’s dramatically lit image on Meet the Beatles (which I had mistakenly matched up with John’s voice). For this reason I nearly refused to board the yellow bus to day camp, where my dark suit and fright wig failed to win me a prize on Costume Day. But there was a consolation. I could sit on the windowsill at home with my back to the curtains and the two-dimensional guitar cradled in my arms, and hope that people down on the sidewalk would mistake me for one of them, passing the time in Kew Gardens between stadium shows.

You can fill in the rest yourselves. Of course we watched them on Ed Sullivan. Of course we saw A Hard Day’s Night, on a winter afternoon so frigid that when we came out of the theater, rippling sheets of frozen rain covered the car windows. Of course my father bought the mono (i.e., cheaper) Capitol LP of Sgt. Pepper, with its speedier, sprightlier version of “She’s Leaving Home.” Of course we moaned and mourned when they broke up and Paul spilled his guts to Life magazine, and we waited patiently for the reunion that never took place and were shocked when one, then another of our household gods died.

John’s murder in 1980 seemed at once impossible and, in a country overflowing with handguns and cult-of-celebrity nut jobs, logical. George contended two decades later with a similarly deranged assailant at home before dying, disturbingly enough, of natural causes. Well, lung cancer — the natural outcome of a million cigarettes, a regular person’s way of extinguishing himself. Not that the Quiet Beatle saw it as any kind of dramatic interruption, since he sided with the Bhagavad Gita on the question of immortality: “There never was a time when you or I did not exist. Nor will there be any future when we shall cease to be.”

There is no future in which the Beatles shall cease to be. This month marks the fiftieth anniversary of their arrival in the United States, a country they conquered with laughable ease, neatly reversing the cultural polarity between the two nations. The Cuban heels, the collarless Pierre Cardin suits, the hair (which in George’s case achieved a kind of turbine or onion-dome effect) — these were envied and imitated by a generation of Americans. John later snickered at the impoverishment of the New World as they found it in 1964. They had been warned that America was a tough nut to crack and the ruination of many a British show-biz stalwart. “But we knew,” John said:

We would wipe them out if we could just get a grip on you. We were new. When we got here, you were all walking around in fucking Bermuda shorts with Boston crew cuts and stuff on your teeth. . . . There was no conception of dress or any of that jazz. I mean, we just thought, “What an ugly race.”

Within weeks, the ugly race was at their feet. I won’t dwell on the band’s commercial success. I won’t even dwell on their rapid transformation of show business itself — the way they wrenched control of the product away from the suits and the white-coated technicians at EMI, sparking not only an aesthetic revolution but an amusing chapter in the history of class warfare. On the recently released On Air: Live at the BBC Volume 2, for example, the radio hosts speak in the plummy idiom championed by the network, while the Beatles confidently toy with them in blue-collar Scouse. The future, it is clear, belongs to the performers, while the hosts sound like relics of the Jazz Age, which is when Lord Reith first imposed that self-conscious intonation on his corps of BBC announcers, who also wore tuxedos while reading the news.

No, I want to dwell on the extra-musical power of the band, on their strange capacity to be welcomed as avatars of something: peace, love, heightened consciousness. Timothy Leary took this view about as far as it could go, memorably declaring that the Beatles were “prototypes of evolutionary agents sent by God, endowed with a mysterious power to create a new human species, a young race of laughing freeman.”[1]

But this tendency has persisted far beyond the Sixties, when people said plenty of things they would hastily retract during the Seventies. In Jonathan Lethem’s novel The Fortress of Solitude (2003), one character argues that the Beatles are a Rosetta Stone for almost every human relationship, especially those involving group dynamics: “The Beatles thing is an archetype, it’s like the basic human formation. Everything naturally forms into a Beatles, people can’t help it.” Using Lethem’s taxonomy, I conform to the “responsible-parent” role, which makes me Paul, which resonates with my primeval confusion back in 1964. I wanted to sound like John, but I wanted to be Paul, with his dimpled chin and quizzically cocked right eyebrow.

Surely the music, as gorgeous and intricate and life-enhancing as it is, can’t account for this sort of fetishistic devotion. In my own way, I’m as bad as Lethem. I’ve played the albums continually throughout my adult life — even during the drought years of the Eighties, when John was gone and George was brooding on his Henley estate and Paul was putting out stinkers like Press to Play and Ringo was, well, crashing cars and finding that “those nights when you drink more than you remembered had become almost every night.”[2] I’ve also collected a mountain of bootlegs, books, and memorabilia, the sum of which is strangely self-diluting: the more you have, the less you need it.

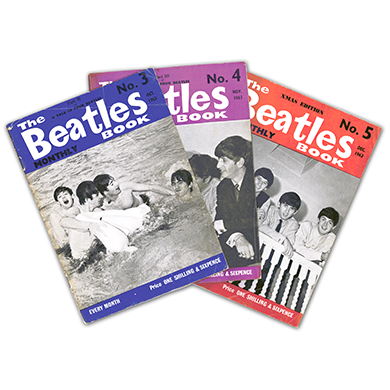

A foggy recording from the very day John and Paul met at Woolton Parish Church in 1957? Got it. Endless reels of tomfoolery from the Let It Be sessions? Check. Recent, slender volumes about the band’s legacy in Hamburg and Russia, as well as something called The Beatle Who Vanished, about the drummer who filled in for an ailing Ringo for precisely thirteen days in 1964? Right here on the shelf. And let us not overlook my treasured issues of the monthly Beatles Book magazine, which sold for one shilling and sixpence back in 1963, and which featured advertisements like this one from Weldons of Peckham Ltd. for the official Beatles sweater:

A foggy recording from the very day John and Paul met at Woolton Parish Church in 1957? Got it. Endless reels of tomfoolery from the Let It Be sessions? Check. Recent, slender volumes about the band’s legacy in Hamburg and Russia, as well as something called The Beatle Who Vanished, about the drummer who filled in for an ailing Ringo for precisely thirteen days in 1964? Right here on the shelf. And let us not overlook my treasured issues of the monthly Beatles Book magazine, which sold for one shilling and sixpence back in 1963, and which featured advertisements like this one from Weldons of Peckham Ltd. for the official Beatles sweater:

High fashioned black polo sweater in 100% Botany wool. Designed specially for Beatles people by a leading British manufacturer. The two-tone Beatle badge is embroidered in gold and red. One size only — fashioned to fit the widest possible range of average-sized girls.

That was the peculiar genius of the Beatles: their music was fashioned to fit the widest possible range of average-sized girls, boys, men, women, parents and children, aunts and uncles, squares and bohemians. This had nothing to do with selling out, no matter how viciously John would later ridicule Paul’s penchant for “granny music.” The band had come out of a pre-Balkanized popular culture, in which skiffle and early rock-and-roll coexisted with show tunes, country, traditional jazz, and the vaudevillian silliness of the British music hall. As late as 1962, during their failed audition for Decca Records in London, the Beatles were still playing such Twenties chestnuts as “The Sheik of Araby,” along with “September in the Rain,” written in 1937 by the Tin Pan Alley Stakhanovite Harry Warren (who also contributed music to innumerable Looney Tunes cartoons). It was all theirs for the taking — and they took it.

Because I’m a skeptical person, I tend to grow suspicious of the things I love. Which is why I’m wondering whether a half-century after the Beatles landed at JFK, it might be time to give them a rest. The demographic cohorts following my own will never attain our heights of Fab Four worship. And indeed, their impatience with Boomer culture strikes me as completely reasonable. The giants of that era keep sucking the air out of the room, don’t they? Imagine being told that guys in their seventies are still better than anything your own generation can produce. Imagine being peddled, year in and year out, a rosy View-Master panorama of that departed age, like Periclean Athens plus paisley and blotter acid.

No wonder a kind of Beatles fatigue has set in. Let the contemporary idols — Kanye West, Lady Gaga, Radiohead, Taylor Swift — have their turn. Whether their music will still sound as fresh fifty years hence is anybody’s guess. But you could make the same argument about, say, Monteverdi, whose operatic masterpiece L’incoronazione di Poppea went into a three-century-long hibernation after his death, only to find popular success right around the time the Beatles were recording “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

Meanwhile, I’ll admit that my hoard of memorabilia functions quite literally as a fetish object: a magical means of accomplishing an impossible end, which is stopping time. The Beatles are supposed to keep me from growing old. Having given up the ghost as a band while they were still in their twenties, they will always be suspended in a kind of youthful amber. But even during their heyday, they seemed weirdly immune to decay. It wasn’t simply a matter of age or physical beauty, which they had in spades. (The composer Ned Rorem once tellingly compared them to a “choir of male nymphets.”) There was something else, a kind of efflorescence, an animal joy at having the world eat out of your hand, which even their customary North-of-England irony could never quite defuse.

Ordinarily this sort of radiant youthfulness dies with youth itself, or is at least transformed into the flickering, low-voltage glow of maturity. It would be no more than a nostalgic touchstone for performers and audience alike. But just as the Beatles were an exception to the iron rule of show-biz transience, so too has their fan base clung to its own version of eternal youth.

I’m talking about the Boomers again — those inheritors of easy money and injection-molded plastics and a distinctly sunny attitude to the future, no longer shared by many of their offspring. The Boomers simply will not leave the stage. Botox and Viagra have made them as shiny and virile as teenagers; in the TV ads for wealth-management services and erectile-dysfunction pills, they gambol around the rolling acreage of their vineyards or hold hands in adjacent plein-air bathtubs or play electric guitars just like you-know-who. They have, in other words, violated the generational compact.

This applies not only to their death grip on cultural matters, but to politics as well. For the past six years, a post-Boomer named Barack Obama has occupied the White House. (Although Obama was born just prior to the 1964 cutoff, his eagerness to distance himself from the identity politics and civil-rights struggles of the Sixties puts him firmly in the post-Boomer camp.) But who seems most likely to succeed him, at least on the Democratic side of the aisle? That would be Hillary Clinton, the once and future queen of her generation, with her ageless, saxophone-blowing consort in tow. And of course she’s a Beatles fan, with a particular weakness for “Hey Jude” — because, as she told a 2009 interviewer, it’s “almost Biblical in meaning.”

In the same interview, conducted while Clinton was enmeshed in nail-biting negotiations with Afghanistan and North Korea, she gently declined to name “Revolution” as one of her other Beatles favorites. That seemed prudent as the secretary of state inched her way from one geopolitical powder keg to the next. Yet Clinton needn’t have worried. The Beatles were musical revolutionaries but ideological centrists. Even in “Revolution,” his most blistering political pronouncement to that point in his career, John washed his hands of Chairman Mao and the very idea of armed struggle, insisting that consciousness was the real battleground: “You better free your mind instead.” (Nina Simone famously responded with a song of her own, also called “Revolution,” in which she suggested that a little violence might be appropriate — love wasn’t all you needed, certainly not in the America of the late Sixties.)

That was then. And what about now? Because I’m a sentimental person, I feel a notable tenderness toward the surviving Beatles, who were actually pre-Boomers and therefore seem like both peers and parents. Ringo tours, writes children’s books, is decorated by the French government (the ceremony, according to his website, took place “in front of the Oceanographic Museum in Monaco”), wants to save the rhinos. Paul keeps making records: standards, electronica, pop, classical. His voice, once a kind of national treasure, has frayed and begun to wobble, and there is something tremendously touching about this weakness, so at odds with his cultivated boyishness. He is, I suppose, the primary keeper of the Beatles flame, toward which his attitude is understandably possessive. “They can’t take it from me, if they tried,” he sings in a recent song, spurning Auto-Tune and letting his 71-year-old vocal cords wander where they will. “I lived through those early days.” As it turns out, he is no more prepared to let go than we are.

1 This wasn’t, by the way, a random emission from Leary’s acid-addled mind. In The Politics of Ecstasy (1968), he called them the “Four Evangelists” and added: “To future social historians I humbly suggest that the spiritual cord that holds our civilization from suicide can be traced from the Himalayan forests where Vedic philosophers drank soma, down the Ganja, through the Suez by P. and O. and over to Liverpool.” His previous book, published just a year earlier, was perhaps not coincidentally called Start Your Own Religion. (back ^)

2 The quote is from Alan Clayson’s Ringo Starr: Straight Man or Joker? (1996), surely among the most acid of Beatle biographies, along with the same author’s George Harrison (1996). Clayson is not a finger-wagging churl in the manner of, say, Albert Goldman in The Lives of John Lennon (1988). He celebrates both the music and the all-too-human frailties of its creators. Yet there is an iconoclastic glee in reading passages like this one, as if God Himself has been caught in his bathrobe (or dhoti): “Old at 31, a crashing bore and wearing his virtuous observances of his beliefs like Stanley Green did his sandwich board, [Harrison] was nicknamed ‘His Lecturership’ behind his back. Visitors to Friar Park tended not to swear in his presence. In deference to their vegetarian host . . . some would repair to Henley restaurants to gorge themselves with disgraceful joy on steak and chips, mocking over dessert George’s proselytizing.” (back ^)