Before he became a novelist, Haruki Murakami was a jazz fan. He got into it when he was fifteen, after seeing Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers perform in Kobe in January 1964. The lineup that night was one of the most celebrated in the band’s three decades of existence, featuring Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Curtis Fuller on trombone, Wayne Shorter on sax, and Cedar Walton on piano. “I had never heard such amazing music,” Murakami said. “I was hooked.” Ten years later, he postponed his university studies to open a jazz club in suburban Tokyo, naming it Peter Cat, after one of his pets. In 1977, he and his wife, Yoko, moved the club to Tokyo’s central Sendagaya neighborhood, where he wrote his first two novels, which led to later books whose titles referenced doo-wop like the Dells’ “Dance Dance Dance” and jazz tunes like Fuller’s “Five Spot After Dark.” The music equally influenced his writing style, which he sometimes conceived in terms of jazz rhythm, improvisation, and performance.

While I was planning my first trip to Japan, I decided to visit the site of the club, which closed in 1981. I love Murakami’s writing for many reasons, some of which have to do with jazz. I like how each book is different from the others. I like how he varies his subjects and narrative voice. I like his stories’ inherent darkness and their cats and quiet humor, and the way he confronts large issues, from devastating earthquakes to the universal devastation of abandonment. Murakami also provided me a window into Japanese culture and mind, which many outsiders think they get, though few do.

Before I left, I read After Dark. The novel takes place in the capital over the course of a single night. It seemed like a great entree to the Tokyo beyond the shrines and shopping districts — to its fringes, where you might encounter unconventional people, including those who commit Japan’s relatively small number of crimes. After Dark was also a book filled with jazz: A trombone-playing protagonist. A bar spinning Duke Ellington records. Frequent allusions to songs. A title borrowed from one of my favorite hard bop tunes. The novel got me thinking about the source of Murakami’s musical passions, and when I followed the trail from After Dark, it led back to his college years, and to Peter Cat.

Unfortunately, no one seemed to know the club’s address — not Murakami’s translator, Jay Rubin, nor the fan who runs Haruki Murakami Stuff. After comparing Google’s map of central Tokyo with a satellite shot from a Japanese website, I switched to street view and scanned block by block, searching for the corner building depicted in a photo I’d seen on the blog A Geek in Japan and checking off intersections on a hand-drawn map as I went. Finally, there it was: a drab three-story cement building. Outside, a first-floor, a restaurant had set up a sampuru display of plastic foods. Above it, an orange banner advertised DINING CAFE.

The first Peter Cat occupied a basement near Kokubunji Station. The club served coffee during the day, and drinks and food at night. On weekends, it hosted live jazz. In a smoky, windowless room, Murakami washed dishes, mixed drinks, swept, and booked musicians. When bands weren’t performing, he spun records from a collection of 3,000 (which has since grown to more than 10,000). The next Peter Cat occupied a second-floor space with windows, a grand piano, and enough space for a quintet. The Murakamis decorated it with cat coasters, cat matchbooks, and cat figurines. Business was brisk.

Before visiting the site of the club, I’d stopped at the same Shinjuku bookstore where Murakami had bought the paper and pen he used to write his first novel, purchasing for myself his nonfiction book Portrait in Jazz in Japanese. No English translation exists, though Italian publisher Giulio Einaudi Editore created a Pinterest board of the albums it mentions, and The Believer published three translated selections from the book in its 2008 music issue.

When I emerged from Sendagaya Station, the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium shimmered in the sun. I made my way past apartment buildings, noodle shops, and a 7-11 before arriving, two and a half blocks away, at the intersection I’d seen online. A sign above the basement read CHACO AMEMIYA, SINCE 1979. That fell within Peter Cat’s lifetime, so I went downstairs. A waitress greeted me with a peace sign. “Lunch, two,” she said. Staff in white uniforms were sharing a meal before service began. Charlie Parker played overhead. Waving my finger around the room, I asked her, “Haruki Murakami? Jazz club here?” After some confusion and explanation, she wrote “2F” on a piece of paper and said, “Haruki, no,” crossing her wrists in an X.

I went upstairs to the restaurant, where the scent of curry greeted me. A waitress came up to me, and I wrote out “Haruki Murakami” in English for her. “Oh, oh,” she said, “sumimasen,” and led me to a man who spoke some English. “Murakami?” he said. “Upstairs. But he is gone now.” He sat me down. “Have you had lunch?” He introduced himself as Tatsuya Mine and said he was a freelance photographer. Another restaurant, Jamaica Udon, occupied the second floor now, but it was closed for remodeling. Tatsuya and the cook exchanged words and laughed. Then the cook suggested a bookstore down the street where Murakami used to shop.

Tatsuya and I went down the street and entered Book House You, where an elderly man sat behind the register. After introducing himself as Tasuku Saito, he stood up, peeled off his glasses, and laid a few photocopies on the counter. One showed a signature that the author had given to Saito, who had then photocopied and pasted it onto the transcription of an anecdote about the bookstore that Murakami had told during a lecture.

A boy came into the store and asked Saito for Horn of the Deer. The owner didn’t know the book, so he asked the boy some questions, and they figured out that he wanted Eye of the Rabbit. Then Saito pulled out two more artifacts from his collection: a DVD case labeled Dinner with Murakami and a book containing pages Murakami had written about the Hatonomori (Pigeon Forest) shrine across the street. Tatsuya couldn’t translate much of what Saito was saying, so we agreed to return two days later.

When we came back, this time with Tatsuya’s friend Yasu along to interpret, Saito recounted his experiences with Murakami. “Mostly his wife shopped here,” he said with a laugh. “He just followed along. He bought more magazines than books.” After the Murakamis opened Peter Cat, they invited their neighbors to visit. Saito went once and enjoyed it, but he could tell that it was a place for enthusiasts; many of the staff went on to careers in music. People in the neighborhood thought, based on Murakami’s record collection, that he was more likely to succeed in music than in literature, though Saito recalled that the author would walk around the neighborhood, strolling and taking notes.

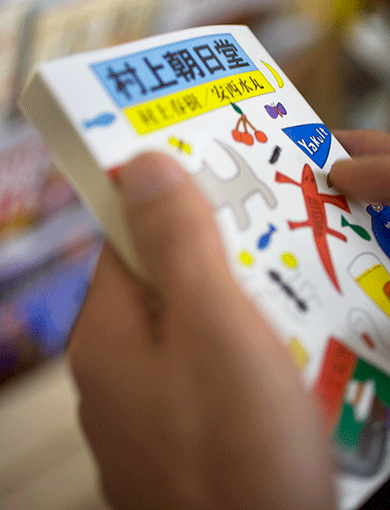

Now that he could make himself understood, Saito didn’t want to stop talking Murakami. He fetched an untranslated essay collection called Murakami Asahi-do from the shelves, describing a piece about Murakami’s barber, whose shop was next to the bookstore. I bought a copy, adding to my collection of books I couldn’t read.

After we left, Tatsuya took Yasu and me to a corner shop where we sat outside and drank tea. Tatsuya’s friend owned it. They played in a band together. Bicyclists peddled by as people said prayers at the Hatonomori shrine on the opposite corner. Yasu lived a few miles away but hadn’t spent much time in Sendagaya. “It’s very nice,” he said. I asked Tatsuya the name of the street we were on. He pointed at the pavement. “This street? No name.” He smirked as if acknowledging some mystery. “We Japanese don’t name streets. We call it Station Street.” He stared north toward the station, in the direction I would eventually go.

In Murakami’s novel Dance Dance Dance, the unnamed protagonist leaves a movie in Tokyo’s Shibuya district and takes a long walk. “I walked, through the swarming crowds of school kids,” he says, “to Harajuku. Then to Sendagaya, past the stadium, across Aoyama Boulevard toward the cemetery and over to the Nezu Museum. I passed Café Figaro and then Kinokuniya and then the Jintan Building back toward Shibuya Station.” The area had left an impression on Murakami, as he had on it. And on me, though I was only passing through. But I did have Murakami Asahi-do, with its colorful illustrated cover and its essay about the Sendagaya barbershop — an impenetrable text I might never absorb.

The book fit in the palm of my hand. Tatsuya saw me flipping through it and laughed. “It’s upside down,” he said. It was backwards, too.

—

Aaron Gilbreath has written nonfiction for the New York Times, The Oxford American, The Kenyon Review, The Paris Review, and the Virginia Quarterly Review. He wrote the musical appendix to The Oxford Companion to Sweets and the ebook This Is: Essays on Jazz, and is working on a book about crowding.