The City of No

Fremont, Nebraska, votes to keep its anti-immigration ordinance — at a possible cost of millions

Tensions in a long-running debate over immigration threatened to boil over in Fremont, Nebraska, on Tuesday, as voters went to the polls for a special election that would decide whether the city repealed key portions of its controversial Ordinance 5165, which requires renters to prove their citizenship in order to acquire occupancy licenses, and makes it a crime for landlords to rent to undocumented immigrants.

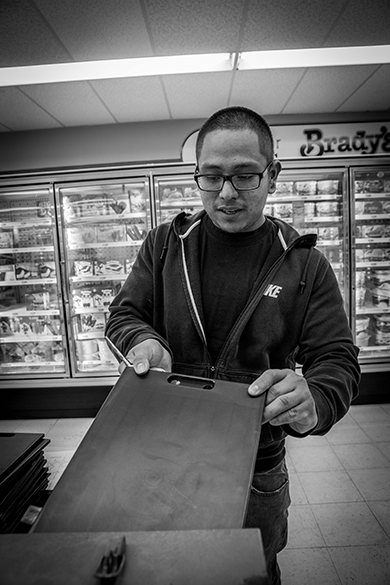

Poll workers at the Precinct 3C voting station — which had been relocated to the frozen-foods section of Brady’s Meats & Foods just before the election because it was the only wheelchair-accessible building on Fremont’s poor south side — told me they had been forced to ask several people to leave. One woman, upon discovering that she was disqualified from voting because her home was technically outside city limits, pointed at Hispanic voters waiting to cast ballots and demanded to know, “Why do they get to vote, and I don’t?”

But by the time the polls were set to close, the wind had picked up outside and temperatures plummeted, cooling tempers and reducing the flow of voters to a trickle. Bryan Lopez, who guts cattle on the kill floor at Cargill Meat Solutions in nearby Schuyler, filled out his ballot at a table next to refrigerator cases filled with ice cream, then dropped the form into the locked box. “I voted ‘Yes,’ ” he told me, but he wasn’t optimistic that a majority would join him in voting to strike down the ordinance. Of those intent on keeping it, he said, “I hope they’re making an educated decision, instead of just being on the bandwagon.”

His worry echoed concerns raised by ordinance opponents, who have long argued that anti-immigration fervor led Fremont voters to approve a measure that does considerable financial damage to the city and addresses none of its underlying problems. Before the 2010 ballot measure that approved the ordinance, many people didn’t know that the Hormel Foods plant, which attracts undocumented workers to the Fremont area, and the Regency II trailer park, where many of those workers live, both fall outside the city limits and would therefore be exempt from the employment and housing provisions in the ordinance. Nor did people know that the city would have to lay off employees and raise taxes to build a $1.5 million legal-defense fund.

Worst of all, Tim Butz, assistant director of the Fair Housing Center of Iowa and Nebraska, warned the city council last October that there was a high risk that enforcement of the ordinance would be viewed as a violation of the Fair Housing Act. If so, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) could deny future Community Development Block Grant funding — and even demand repayment of millions of dollars in federal grants paid out to the city for downtown revitalization after the ordinance passed in June 2010. “I’m here to tell you that you need to act,” Butz told the city council. “You cannot ignore this thing. You’ve got to do something to counteract the effect of the ordinance on the Hispanic population of this city.” After a series of contentious meetings to consider the matter, the city council voted to give the people of Fremont a chance to reconsider the ordinance.

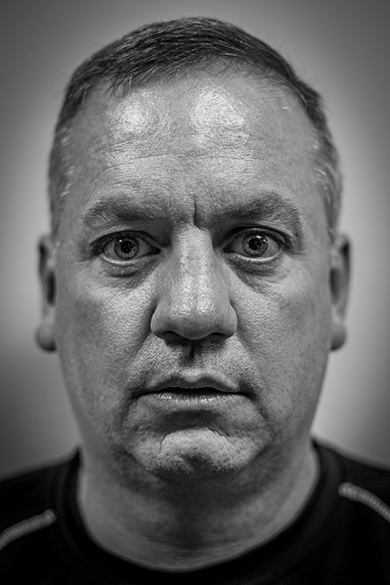

Mayor Scott Getzschman and several council members voiced their hope that Fremont’s citizens, with benefit of hindsight, would vote to repeal the housing portion of the ordinance. Instead, as soon as the polling stations closed, early results showed that not only had voters upheld the ordinance, the margin of victory had widened.

Blake Harper was disappointed by the outcome but not surprised. Harper lives in Pennsylvania now, but he grew up in Fremont and owns a handful of duplexes there. After the first vote in 2010, he signed on to become the named plaintiff in a joint lawsuit against the City of Fremont, brought by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF). “I’m embarrassed and ashamed, but I’m not shocked that Fremont has enough closet bigots to carry the vote,” Harper told me soon after the election results were posted. Then he sighed. “Well, maybe not so closeted.”

In fact, on the east side of town, the pro-ordinance group Our Votes Should Count held a loud celebration at the Gathering Place, complete with an impassioned address by State Senator Charlie Janssen (R.). There were cheers and applause as the final tally — 60 percent opposed to the repeal, 40 percent in favor — was held up on poster-board signs. A big band struck up, and people started dancing. Janssen slipped into the icy quiet outside to field a few phone calls from reporters. “It is pretty rocking inside,” he told one. “They’re enjoying an evening that culminated several years of hard work.”

John Wiegert, a leader of Our Votes Should Count, was arguing that this vote should never have happened. In the winter of 2008, he and his fellow petitioner Jerry Hart had gone door-to-door gathering the necessary signatures to put the measure on the ballot. The ordinance won a 57 percent majority, and its language has stood up in the courts. Last year, after ordinance supporters won an unexpected victory in the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals, despite rulings in other district courts against similar provisions passed by Farmers Branch, Texas, and Hazleton, Pennsylvania, Wiegert and others had expected to see the law enacted and enforced. Now the city was out of excuses.

For ordinance opponents, the defeat stung all the more given how much support they had rallied. The group Fremont YES had raised $71,000 for yard signs and advertising, compared with just $8,000 brought in by ordinance supporters. In the run-up to the special election, Mayor Getzschman appeared in a pro-repeal TV commercial. A slate of ads ran on local radio. The editors of the Fremont Tribune endorsed the Yes vote. The owner of a billboard at the far end of the overpass crossing the Union Pacific tracks — the most visible spot in town — donated the space to Fremont YES. Despite all the effort and expenditure, Harper said, “we didn’t move the needle at all.” And emboldened ordinance supporters are vowing to ride their momentum into efforts to recall Getzschman and the council members who brought the repeal to the ballot.

Harper speculated that Fremont’s problems would only grow now, as more young people moved to Omaha and Lincoln, and more immigrants arrived in Fremont to work. “As long as Hormel is processing 1,300 hogs per hour,” he said, “there will continue to be high demand for low-wage, unskilled labor. This is a demand that cannot be filled by the local workforce and cannot be stymied by silly ordinances.”

I asked Harper what his next move would be. He paused a moment then laughed. “You want to buy some duplexes in Fremont?”

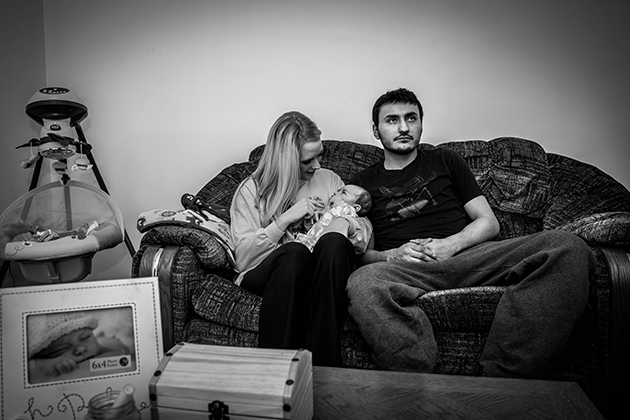

Jonathan Chavez, Kayla Jacquart, and Jameson in their apartment in Fremont, Nebraska © Mary Anne Andrei

A few blocks south of the Gathering Place, where the party was ramping up, Jonathan Chavez, one of Blake Harper’s renters, was just returning home from a twelve-hour shift at Midwest Manufacturing in Valley, about ten miles down the highway from Fremont. His girlfriend, Kayla Jacquart, patted and burped their five-week-old son, Jameson. Last July, when Jacquart found out she was pregnant, the couple started looking for an apartment. She spotted the for-rent sign here, and after Chavez talked to Harper at length, they decided this was the place for them. “It’s two bedrooms — so he has his own room,” Jacquart said, bouncing Jameson on her knee. “It’s perfect for us right now.”

Jacquart has been completing a degree at Metropolitan Community College in Omaha, and Chavez, who recently graduated from Midland College, said he is hoping to pursue a masters in business management in the fall. He was working as a shift manager, and figured that an advanced degree would help his chances of becoming a plant manager one day. When that happened, he said, breaking into a broad smile, “We can get out of here and get our own place. Get out of Fremont.”

Like many people in Fremont and Schuyler, Chavez was born in the Mexican mountain town of Chichihualco and came to the United States when he was still a toddler. After his parents split, his mother bought a trailer in Regency II and went to work on the line at Hormel. It was a hard life, he said, but he took issue with the way that the trailer park had become a stand-in for Fremont’s ills. “If you come here and don’t have documents and only Hormel is going to hire you, that’s all you can get,” he said. “Obviously, it’s trailers. It’s not nice fancy homes. But people are people.” He said he’d had a happy childhood, holding down a 3.75 grade point average in high school and receiving academic and soccer scholarships to Midland.

Fremont’s affirmation of the ordinance was unlikely to stop the influx of immigrants willing to make the journey from Mexico and work jobs at Hormel in order to give their kids a better life. All it meant, Chavez said, was that young people like him, once they’d received their educations and were ready to work and start families, would get as far away from Fremont as possible. That was certainly his plan. But, for now, he had to get some rest. Jameson was finally quieting down and ready for bed, and Chavez had to be back up and on the road to work by 5 A.M.