“That’s another thing we’ve learned from your Nation,” said Mein Herr, “map-making. But we’ve carried it much further than you. What do you consider the largest map that would be really useful?”

“About six inches to the mile.”

“Only six inches!” exclaimed Mein Herr. “We very soon got to six yards to the mile. Then we tried a hundred yards to the mile. And then came the grandest idea of all! We actually made a map of the country, on the scale of a mile to the mile!”

“Have you used it much?” I enquired.

“It has never been spread out, yet,” said Mein Herr: “the farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight! So we now use the country itself, as its own map, and I assure you it does nearly as well.”

—Lewis Carroll, Sylvie and Bruno

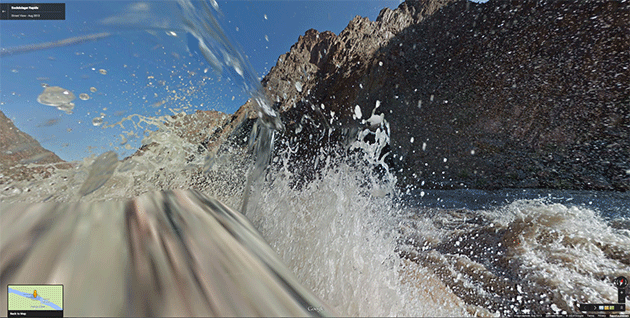

In March, Google released its latest digital creation, a river-level view of the entire Grand Canyon — all 286 miles of it, from Lee’s Ferry on the canyon’s northern end to Pearce Ferry on its southern. The company’s programmers compiled some 57,000 360-degree panoramic images shot by a raft-mounted camera to create the virtual trip. Additionally, hikers wearing Google-built “Trekker” backpacks captured panoramas of several inner-canyon trails. The Street View Grand Canyon is an offshoot of the company’s well-known Street View feature, which millions have used to rove suburban cul-de-sacs or back roads of exotic cities.

Google says it embarked on the Grand Canyon project with conservation in mind, in partnership with the environmental group American Rivers, which in 2013 declared the Colorado the country’s “most endangered” river. The hope, according to a Google release, is that those who take the virtual journey will become engaged in protecting the real waterway.1

Google says it embarked on the Grand Canyon project with conservation in mind, in partnership with the environmental group American Rivers, which in 2013 declared the Colorado the country’s “most endangered” river. The hope, according to a Google release, is that those who take the virtual journey will become engaged in protecting the real waterway.1

1 Mind you, a tour of the Colorado as it passes through the Grand Canyon — where it is has the benefit of being designated a national park — might be less effective in helping to raise awareness than showing, say, the iridescent uranium tailings ponds along the Colorado’s banks near Moab, Utah, or the stretches of the Green River, a tributary of the Colorado, that pass through the Uintah Basin’s great gas fields.

The project interested me because in 2011, I received a grant from Stanford University’s Bill Lane Center for the American West to build an interactive digital map of the Grand Canyon — albeit one far less technologically ambitious than Google’s. The grant came after years of compulsively studying and tracking a forgotten artist, cartographer, and explorer named Friedrich W. von Egloffstein, who made the first map of the canyon.

The Bavarian-born Egloffstein traveled along the 38th Parallel with John C. Frémont’s fifth expedition in 1853–1854, then with Joseph Christmas Ives’s Grand Canyon expedition of 1857–1858. The map I eventually made of the canyon, working with Lane Center multimedia specialist Geoff McGhee, was a digital recreation of two of Egloffstein’s exquisite shaded relief maps; it appeared on Harpers.org as a supplement to my magazine feature “The Long Draw.”

Egloffstein would, I think, have approved of Google’s latest effort. Toiling in extreme secrecy, he invented and patented a host of technologies to produce his maps, including several processes that allowed photographic images to be transferred to paper. His ultimate goal was to combine overhead map projections with panoramic images of the landscape. The historian J. B. Krygier describes the effort this way: “[T]he specific locations of the panoramas are noted on the expedition’s maps, and one can plot the planimetric extent of the panoramas by calculating the bearings from the point located on the map. . . . This feature ties the panoramas to the map, and the map to the panoramas.” In other words, Egloffstein was creating the nineteenth-century equivalent of Street View.

I was dazzled the first time McGhee and I saw the virtual landforms of Google Earth poking up from under the antique map like a tablecloth draped over an Old West train set. Overlaying old charts on Google’s mosaic of the modern West felt almost subversive, like a rejection of modernity itself. We built the map so that you could strobe instantly between past and present or crossfade one map with the other, transforming the blank spaces of the unexplored canyon into the jumble of roads, hotels, and gift shops strewn along the Grand Canyon’s rim today.

But if our Egloffstein overlays allowed for nostalgic dips into the nineteenth century, Google Earth’s Grand Canyon reveals the advantages of modernity, permitting instant travel across miles of fractured terrain, thereby nullifying time and distance, the very factors that vexed early expeditions as they searched for transcontinental-railroad and military routes — the roads by which the American West was conquered.

Google’s declared mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” a statement that casts the planet as a vast and undifferentiated stream of data, awaiting processors and algorithms powerful enough to transform and order it for human use. And so, in the spirit of the mile-to-mile scale map of Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno, the company has captured the canyon with tremendous accuracy, allowing anyone with a computer and a decent Internet connection to “cover the whole country.”

To better understand how — and more importantly, why — this capturing has been carried out, I arranged a meeting with Karin Tuxen-Bettman, a “geo data strategist” and the project lead for Google’s Grand Canyon mapping effort. Before setting out from my home in the East Bay, I typed my destination into my smartphone. Then I somnambulantly followed its commands southward, across Dumbarton Bridge and into the labyrinth of identical office buildings that comprises Google’s sprawling Mountain View complex.

After I’d parked and wandered aimlessly for a few minutes, Google spokesperson Susan Cadrecha called out my name from across the lot.

“I’m usually pretty good with maps,” I said sheepishly.

“It’s okay,” she replied. “Everything sort of looks the same around here.”

We passed through a silent office building — one of several belonging to Google’s mapping division, the company’s largest single branch — and into a courtyard of picnic benches topped with umbrellas in the company’s blue, green, red, and yellow logo colors. There we met with Tuxen-Bettman. The wind was brisk, and she brushed her brown hair from her glasses as she spoke. As a teenager, she told me, she’d taken a raft trip through the Grand Canyon, from Phantom Ranch to Whitmore Ranch, which influenced her decision to earn a Ph.D. in environmental science.

She said she’d read up on Egloffstein the night before, and we enthusiastically discussed the perils of the early expeditions — the capsizings, the weather, the threat of violence from local tribes. When I asked her whether Google’s expedition had encountered many challenges, she thought for a moment and responded with what seemed like slight disappointment. “No,” she said, “there really wasn’t.”

She said she’d read up on Egloffstein the night before, and we enthusiastically discussed the perils of the early expeditions — the capsizings, the weather, the threat of violence from local tribes. When I asked her whether Google’s expedition had encountered many challenges, she thought for a moment and responded with what seemed like slight disappointment. “No,” she said, “there really wasn’t.”

So successful was Google’s eight-day expedition, in fact, that not only was no gear lost, but no data went missing. “It was all there,” she said, “an unbroken stream of images.”

As complete as the canyon’s terrain appears through the digital looking glass, however, Street View Grand Canyon feels conspicuously inadequate in critical ways. On the virtual river you can fast-forward downstream, avoiding the soaking rapids and searing sun, putting in and taking out as you please. But part of the Grand Canyon experience is surrendering to the flow of the river and committing to the journey. Anyone who has traveled in canyon country knows how much the terrain can change in a matter of seconds during an afternoon rainstorm, or in the hours between noon and dusk, as sunlight glistens and fades upon the canyon walls. To these subtle but vital gradations, Google’s roving digital eye remains conspicuously blind.

I’d heard these shortcomings voiced by proud river runners and backpackers, often delivered with mild condescension (“I guess I can cancel my rafting permit for this summer”) or outright indignation (“Is nothing sacred?”). Jonathan Thompson, an editor at High Country News, invoked the cantankerous author Edward Abbey, who in the 1970s wrote, “The utopian technologists foresee a future for us in which distance is annihilated and anyone can transport himself anywhere, instantly. . . . To be everywhere at once is to be nowhere forever, if you ask me. That’s God’s job, not ours.” Tuxen-Bettman made a similar concession, pointing out that the map and its imagery were no substitute for the canyon itself. “It reflects what’s there at one moment of time,” she said, “but it does not replace it.”

Despite its gaps, Google’s digital map is seductive. The interface is elegant and intuitive, and the panoramas on view are captured dispassionately, seemingly immune to the emotional coloring and exaggeration for which the first artists of the canyon, including Egloffstein, have been criticized. But the Street View cam, like all cameras, produces its own kind of distortion. Its wide-angle lenses warp and contort the vertical walls, leaving the viewer with little sense of the canyon’s true proportions. Early expeditionary artists often foregrounded their drawings with human figures in order to convey the vastness of the surrounding landscapes; in his Ives Report images, Egloffstein commonly used a steamship for this purpose.

Those steamships also served to illustrate the forward momentum of the expedition, reinforcing the image of civilization’s march into the uncharted wilderness of the American West. By contrast, nearly all evidence of the human labor involved in Google’s mapping expedition has been wiped away. Faces of rafters and hikers have been blurred for privacy reasons, and the company’s raft has been digitally smeared out into the roiling brown current. “We wanted this to be about the place,” said Tuxen-Bettman, “and not about Google.”2

2 A few traces do remain — places where Google’s automated software has failed to digitally blot out the expedition’s footprints. The occasional shadow of a two-headed hiker saddled with the Trekker sometimes appears on the trail, and some river frames show the hazy edges of the raft or the disembodied heads of rafters, a few of whom can be seen knocking back cans of beer.

As she spoke, I began to wonder about Google’s motives. Much of the angst around the advance of Street View seemed to be implicitly tied to the steady worming of Google’s tentacles into our private lives. Having absorbed search histories and other markers of online behavior, to what use might the company put virtual interactions with wildest nature? If, as Tuxen-Bettman insisted, the Grand Canyon project wasn’t about the company — and wasn’t meant to be a high-fidelity representation of the real thing — then why bother in the first place? Was the pursuit of technological novelty just a fringe benefit of working for a company whose 2013 revenues totaled more than $50 billion?

A Trekker backpack leaned against the bench beside us. I hadn’t been able to keep my eyes off it. A sphere jutted from the top of the metal frame, covered with fifteen lenses capable of photographing the landscape in all directions simultaneously.

“Do you want to put it on?” Tuxen-Bettman asked.

“Can I?”

“Of course,” she said, helping me hoist the forty-pound pack onto my back. The apparatus was entirely rigid, making it feel much lighter than the packs of similar weight that I’d often carried into the backcountry. When Tuxen-Bettman let go, however, the high-perched camera caused me to jerk backward a little. I cinched the belt and tightened the shoulder straps. Instantly, the device’s center of gravity shifted and it seemed to meld to my body.

Coincidentally, that morning Google had announced a limited one-day release of a number of its face-worn Google Glass computers. Two weeks later, the Federal Trade Commission would approve Facebook’s $2 billion acquisition of Oculus, the developer of a virtual-reality headset called Rift. The two announcements raised the question of whether Google’s effort to capture the world’s landforms was laying groundwork for such technologies. Someday soon, might we see this kind of imagery streamed through a fully immersive headset — a device capable of fooling the senses and delivering a high-definition map of Carrollesque proportions directly to our optic nerves?3

3 The answers to those questions, it seems, will have to wait. My follow-up questions to Cadrecha were met with emails that read, “We have no plans to announce at this time.”

Cadrecha told me Google was embarking on a program to loan the Trekker out to private citizens, allowing them to capture a virtual journey to their favorite secret places. The record of those journeys would of course be available for public consumption in Google’s ever-growing Street View archives. “You might think about joining us,” she said.

With Google’s digital eye jutting like a second head from my upper back, I contemplated where I might take the Trekker — to a high, unnamed slab in the Wind River Mountains, perhaps, or a slot canyon on the Colorado Plateau, or into the dark maw of the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River itself. But then I recoiled at the thought, and not just because I selfishly wanted these places to remain untrammeled – terra incognita in the public consciousness.

Soon enough, the company would have a camera capable of absorbing every inch of the planet’s most inaccessible landscapes into its databases. But not yet. I pictured the Trekker’s protruding eye striking a low overhang on a high peak or in a deep canyon. Would it be decapitated from the frame? Or would it stay affixed, catapulting me backward over some ragged precipice? The device would pound against bare rock, plunge into murky water, rake against ice. Its GPS sensors would starve for a signal and its fifteen eyes would scuff and crack, eventually growing sightless as they succumbed to water, sand, wind.

I smiled at the thought as I unhooked the waist belt.

“Yeah,” I said. “That would be fun.”