Few people in this world have ever loved trains as much as Alisa Zinov’yevna Rosenbaum, a.k.a., Ayn Rand, the proudly adulterous, cult-leading, atheist, Russian–Jewish immigrant who has somehow become the idol of today’s sexually immured, Christian fundamentalist, xenophobic Republican Party, as exemplified by the primary victory last week of Professor David Brat. Being aboard a western train for my July Harper’s Magazine folio story, as we navigated around washed out rails and dealt with a malfunctioning electrical system while in Washington Republicans were preparing to shut down the federal government, my thoughts naturally turned to Rand.

In her major opus, Atlas Shrugged, railroad management exemplifies the sort of endeavor her great heroes of capitalism, the prime movers, love to take on. She claimed to have taken rides in the locomotives of the New York Central while researching the book, and to have driven the 20th Century Limited, boasting that while she was at the controls of that extraordinary train, “nobody touched a lever except me.” Trains are such an indispensable motif in Atlas Shrugged, that, when some of Rand’s acolytes produced a slavishly faithful film adaptation of her book set in the present day, they had to invent a convoluted rationale involving resource shortages and industrial disasters to explain how railroads had once again become the dominant form of long-distance transportation.

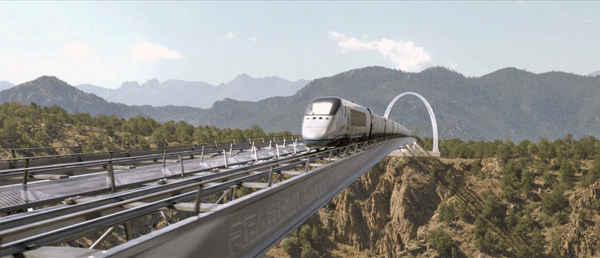

Trains were more than just a magnificent obsession for Rand. They also served as a sort of avenging angel. By Atlas Shrugged’s seventh chapter, “The Moratorium on Brains” (no stickler for subtlety, was our Ms. Rand), so many of the great men have opted out of society that a working diesel engine cannot be found to run a revolutionary express train, the Comet, through an eight-mile tunnel in the Rockies. Nevertheless, one of the “looter” politicians ruining the world insists that the Comet — clearly modeled on the 20th Century, and probably one of the gorgeous new Zephyr trains of the time — make the trip anyway, so that he can make a campaign appearance in California. The spineless, government-appointed bureaucrats now running the railroad attach a coal-burning engine instead, even though they know it might asphyxiate everyone on board.

“It is said that catastrophes are a matter of pure chance, and there were those who would have said that the passengers of the Comet were not guilty or responsible for the thing that happened to them,” writes Rand, who then begs to differ, spending the next two pages ranting about sixteen unnamed individuals who will die aboard the Comet — and a good thing, too, as they embody all the sorts she most despises.

The doomed include everyone from a lawyer who feels he can “get along under any political system,” to “an elderly schoolteacher who had spent her life turning class after class of helpless children into miserable cowards” because they believed in the will of the majority; to “a sniveling little neurotic who wrote cheap little plays” that insulted businessmen, and finally a doting mother of two who would not denounce her husband because of his weaselly government job.

“These passengers were awake; there was not a man aboard the train who did not share one or more of their ideas,” she concludes with relish, presumably including in her condemnation the young tots the doting mother had just tucked into their bunks with visions of collectivism inculcated deep in their heads. To them, Rand adds a group of soldiers aboard a munitions train that runs into the Comet after it stalls in the tunnel, killing everyone in a spectacular explosion.

Rand later writes a scene in which, as the nation’s infrastructure is crumbling during what she terms a “strike” by the prime movers, a rail bridge falls apart and a Taggart Transcontinental train tumbles into the Mississippi River — one more vehicle crowded with thinkers of philosophically impure thoughts. And in yet another scene, Eddie Willers, the loyal aide to the book’s heroine, is aboard a train when it breaks down out in the Arizona desert. The other passengers and crew manage to be rescued by a passing wagon train(!), but Eddie refuses and pleads, “Don’t let it go!” while looking up helplessly at the locomotive. The others abandon the train and Eddie, almost certainly to his death.

It was such passages that led Whittaker Chambers, in his 1957 National Review takedown of Rand and her just-released book, to famously write, “From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard, from painful necessity, commanding, ‘To the gas chambers — go!’ ” By then Rand had lingered so long on her screed that trains, the cutting edge of American technology and design when she began, were about to be all but eliminated by the prime movers.

But reading of her love for trains’ capacity to kill at least allows one to understand her appeal to the modern Republican right. Her extended descriptions of those who will die and why they deserve to die resemble nothing so much as the climactic passages of Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins’s Left Behind series, in which, after another set of righteous people have been raptured out of harm’s way, the authors dwell in loving detail on the torments to be inflicted by the returning deity of the Apocalypse — in this case, not Jesus Christ, but John Galt. Different god, same gas chamber.