Below the Beautiful Horizon

Futebol and family in Belo Horizonte during the opening week of the World Cup

On the opening day of the World Cup, I helped my brother Ramon deliver groceries in the suburbs of Belo Horizonte, Brazil’s third largest city. Driving his boxy new truck with one eye on the road, he thumbed through a batch of receipts to find the address of a home in a neighborhood where milk cows wander the streets, occasionally bringing traffic to a halt. The back of the truck was stacked high with red crates full of beans, cookies, cooking oil, laundry detergent, rice, and other staples that cost more today than they did last month.

When we arrived, Ramon’s client let us inside, and we unpacked her groceries in the kitchen while she and her daughter stood in front of a TV, watching the World Cup opening ceremonies. Dancers dressed as trees, flowers, and soccer balls performed on a bright green pitch in São Paulo for an overwhelmingly white audience. If we could finish our deliveries in time, we’d make it home for the opening match between Brazil and Croatia.

Ramon was giddy with anticipation, not for the game, but for the birth of his first child. In just four days his wife Cristiane was scheduled to deliver a daughter by cesarean section at a nearby public hospital. They married last year, and their lives have never been busier. His freelance driving and her cake-and-candy business have afforded them a house in a neighborhood full of family and old friends. In the evenings and on weekends, they prepared the nursery.

The baby would be born at a tense moment for Brazil. Few here in Belo Horizonte will be able to attend a World Cup game in their own city, adding insult to seven years of hasty preparation plagued by wasteful spending and broken promises. Last June, more than 50,000 people took to downtown streets during the Confederations Cup, to grieve the hundreds of millions in public funds committed to projects that were never finished, or that never broke ground in the first place.

On the way to our next delivery, we drove past signs of the unfinished projects, and of the lack of basic services in many neighborhoods: A hospital that was supposed to offer some of the best services in the country, operating at half capacity after years of delays. A nearby stream brimming with litter that the sanitation department had yet to pick up. A web of unpaved, unlit streets.

“People out here are frustrated,” Ramon said. “They work hard. They’re paying taxes like everyone else. Why can’t they get the roads paved?”

It seemed to be more a question of priorities than of money. On a delivery to a nearby favela, we passed a shiny new military-police car parked at the bottom of the hill. “Para inglês ver,” Ramon said. For the English to see.

All day we passed boys flying kites in the streets, celebrating the first day of a long break from school. It was a familiar scene for Ramon, but one I’d only seen as an adult. I was adopted as an infant in 1981 and grew up in rural Oregon. He was born almost two years later and grew up here as the country transformed from a military dictatorship to a burgeoning democracy. We met for the first time in 2006, and since then we’ve been making up for lost time on Skype and during my visits, staying up late to swap stories, watch YouTube clips, and improve my lumpy Portuguese.

By late afternoon, most of the boys had packed up their kites to go watch the match. We knew it was time for the coin toss when drivers all around us started honking. Ramon joined the racket and tuned the radio to the local news, which was reporting on demonstrations in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and just a few miles away in Plaça Sete, the historical heart of Belo Horizonte, where that night vandals would overturn a police car and strike a Reuters photojournalist in the head with a rock. Yet despite the turmoil in the streets, most folks around town barbecued as we did, donning yellow jerseys and pouring cold beer and going bonkers when Neymar scored Brazil’s first goal of the Cup.

Saturday night, the family gathered at Ramon’s house for the baby shower. We feasted on hot stew and cold drinks while Cristiane sat beside a mountain of diapers and displayed gifts of baby clothes for everyone present. The eldest women in the room were children the last time Brazil hosted a World Cup, in 1950, and they’d raised their own families during the two decades of dictatorship that followed. The youngest children in the room knew about those years only from history books with other chapters focused on the electoral process and freedom of speech.

The next morning, President Dilma Rousseff published a brief op-ed advising Brazilians that soccer transcends politics. She wrote of spending the 1970 World Cup in jail with other dissidents. When the tournament began, she said, many of her cellmates refused to root for the Seleção, fearing that a win for Brazil’s national team would only strengthen the dictatorship. Rousseff wrote that she’d felt no such compunction, and by the time Brazil had sealed its win, everyone in the prison was rooting for the team, too. The editorial was part of a huge government effort to turn the tide of public opinion, a PR campaign to accompany the military one in the streets.

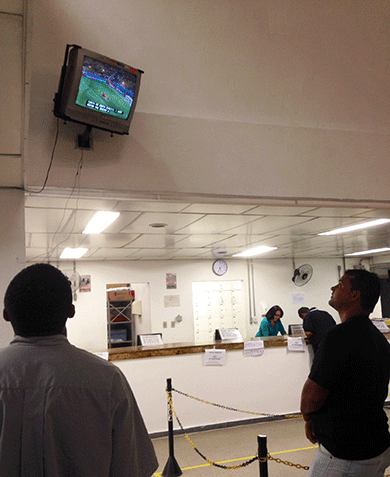

On Monday afternoon, four days after the 2014 World Cup opened, Luana de Souza Santos Feliciano was born at a public hospital near the northernmost stop on the metro line. Visitors were allowed the next day. I arrived during the second half of Brazil’s match against Mexico. In a quiet waiting room, dozens of visitors gazed at a muted television overhead, leaning forward in their seats. We heard cheers and groans from a room down the hallway whenever Brazil attacked the goal.

Only one person was allowed to visit the maternity ward at a time, and for only a few minutes. When my turn came, I found Cristiane and Luana healthy and hungry. Ramon had recorded every moment of the delivery on his camera and proudly showed me a picture of Luana just after he’d given her a bath.

Back downstairs, as the other visitors took their turns greeting the baby, Ramon and I watched the final minutes of the match on the waiting room TV. When it ended in a 0–0 draw, there was commotion from the room down the hall. A clutch of doctors, nurses, and orderlies emerged from the break room and scrambled back to their stations.

“And there you have the health system in Brazil,” said Ramon as the P.A. resumed its regular announcements. “Now the hospital can function again.”