Karine Laval’s Eclipses

Photographs that push the boundaries of what a photograph can be

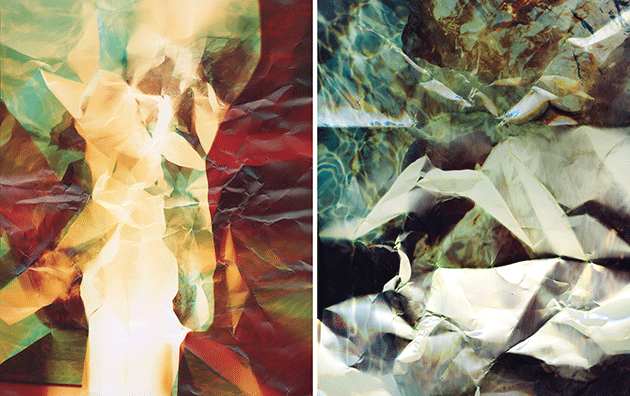

“Eclipse #2” and “Eclipse #1,” crumpled and exposed photographic papers by Karine Laval. Courtesy the artist

A few weeks ago, I stopped by the photographer Karine Laval’s comfortable Williamsburg loft to discuss her newest series, Eclipses, and how her practice has evolved into its current form. Unlike much of Laval’s earlier work, which has been published several times in Harper’s Magazine, these new images are resolutely abstract, seemingly absent the pools, swimmers, and sun-washed landscapes that were her primary motifs. In talking through how she created the colorful topographies of Eclipses, however, it became clear that the series is simply the logical extension of her varied interests, bringing together dance, liquid, and a taste for pushing the boundaries of what a photograph can be.

Born in Paris and trained as an artist in New York, Laval has always been interested in the nature of the photographic gaze, in how it can capture and interpret human experience, and in how it can be altered and subverted. Over the course of several hours and subsequent email exchanges, we moved from Eclipses and the social theater of the pool to the lost transgressive potential of the early BlackBerry camera.

Two works from your new series, Eclipses, appear in the Readings section of our July issue. How were they created?

The Eclipse images are the result of a lengthy process that combines a mix of analog and digital manipulations, including experimentations in the darkroom and with a scanner. The starting point is one of my negatives, whose indexical image I gradually obliterate. First, I physically alter the photographic paper while exposing it in the darkroom, then I allow light leaks and reflections (in the darkroom and the scanner) to leave additional marks that further transform the final image. Paradoxically, this process of erasure is at the same time regenerative: the new forms, colors, and textures create a “near-abstract” image that evokes new topographies or constellations. The title of the series serves as a metaphor for the obscuring and concealment of the indexical images by the new layers of information — mostly abstract forms and colors — resulting from the process.

Eclipses is not only less documentary, but also less representational than much of your previous work. The images are removed enough from recognizable scenes that they are almost abstract. What spurred the move in a more abstract and conceptual direction?

I started to work on this new series last year, as a natural continuation of my last exhibition, Altered States (2012–2013). In that project, I explored the limits of the photographic medium by using water as a distorting lens and shifting the natural colors captured on the film with an experimental chemical process. My aim was to generate images that oscillate between representation and abstraction, and that blur the boundary between photography and painting. I also used Mylar polyester film because it shares reflective and distorting qualities with water, which has been central to my work for a long time now.

Most of my recent projects have to do with the dissolution of the image or the fragmentation of the human figure (in collages, and in series like CRASH, Anatomy of Desire, and Chroma). In a way, I think this move toward abstraction can be seen as a response to the fluidity and dematerialization of contemporary existence. Most of what we experience or communicate is mediated and therefore transformed and in constant state of flux. It can create a sense of chaos and confusion, or a kaleidoscopic and polyphonic perception of our lives.

The work in Eclipses is also more object-oriented, with each work itself a product of an elaborate and intensive process. How does this kind of practice square with the notion of you as a “photographer”?

Over the past few years, I have been increasingly interested in the process of image making — as opposed to image taking — and its relationship to surface, texture, and materiality. At the moment, I find it a more exciting and rewarding approach than “straight” or documentary photography. It allows me to experiment freely and to welcome mistakes outside of the medium’s regular conventions. It is also a more creative and instinctive process, closer to painting or collage, and it has taken me in unexpected directions.

As a child and adolescent, I was very curious and rebellious. I think there is still this child in me . . . even in my early work I consciously defied photographic conventions by aiming my camera directly at the sun, by over- or under-exposing film, by processing it in the wrong chemicals, or by turning the frame upside down — all in order to challenge our familiar sense of perception and to depict a world on the edge of the real and the surreal, of experience and imagination. Eclipses pushes this investigation further, exploring the tension in photography between representation and abstraction, as well as its relationship with painting and sculpture.

Water and pools play a significant role in your work. What attracts you to water as a substance, and to pools as settings?

I’ve always been drawn to water and its edges. I learned to swim when I was very young, grew up sailing with my family, and regularly visited my father in the Caribbean, where he lived when I was a teenager. And I’ve been surfing since I moved to New York in the 1990s. I find water appeasing, meditative, and exhilarating. It speaks to the senses; it’s a vehicle for transformation and self-reflection. It’s also vital to the survival of the planet and our species, and can be a deadly force, as we’re appreciating more and more in studying the impacts of climate change.

I’m interested in all of these aspects of water, from the more intimate and symbolic to the social and economic. For the past decade, I’ve explored notions of space, memory, the human figure, and our relationship with the environment, with a particular focus on water and swimming pools, which are representative (even icons) of our culture and lifestyle. I started photographing public pools in different countries around Europe in 2002, in part as a way to revisit memories from my childhood. I was also attracted to the architectural aspect of the pools, which combine the natural with the artificial in a man-made environment.

People typically think of swimming pools as places of social and physical activity. In this sense they evoke leisure and the pleasures associated with modern life. However, I am also interested in the psychological subtext associated with the image of the pool — in its subconscious ramifications. Like images, pools can be layered with ambiguous connotations. The pool carries a nostalgic but also sometimes macabre undertone that has been explored and exploited in literature and movies. I particularly think of John Cheever’s short story “The Swimmer,” of the decadent pool parties and final murder scene in The Great Gatsby, and of The Graduate, in which the pool is central to the plot. A swimming pool can be a stage for mundane activities but also an arena for anxiety, drama, and tragedy. The stillness of the water reinforces that ominousness.

In my work since the series Poolscapes (2009–2011), water has shifted from being primarily a subject matter to the substance or tool I use to create the work. I employ it as a distorting lens and a revealer of transformed reality. In this sense, the element becomes almost a metaphor for the medium of photography itself.

Theatricality and performance also feature prominently in your photographs — notably in your investigation of the social theater of the pool, as you’ve suggested. Indeed, in Altered States, the figure visible in the water is a dancer. What sparked this interest in performance?

It began in my teens, when I discovered the choreographers Pina Bausch and William Forsythe. I’ve been a big fan of contemporary dance ever since. I also joined a high school theater company led by a teacher and director who was more interested in avant-garde theater than in revisiting the classics, and later moved from the stage to assisting her and being in charge of light design.

Performance is present in my work as early as the series The Pool (2002–2006). The simple but often striking geometrical lines and shapes, evident in both the architecture and the natural light, confer a certain sense of theatricality, which is reinforced by the presence of the exposed bodies, the repetitive gestures and rituals, and the interaction of the bathers with the place. When I photographed these “stages” of leisure and mundane activities, I often imagined that a silent choreographer was orchestrating them as spontaneous ballets. But maybe I am this choreographer, after all, when I frame and freeze the scenes.

The human figure, which is essential to performance, has also been central to my work. I’ve explored its many facets, whether the social body, the body as architecture and landscape, the distorted body as a metaphor for shifting identities, or finally the performative body.

With Altered States, I directed a professional dancer to perform underwater, testing the resistance of his body in an unfamiliar element and under challenging conditions, thus evoking man’s struggle with nature, the uncertainty of the human experience, and ideas of vulnerability and physicality. The isolation of the figure within a field of color (red) stripped the image from any narrative reference and focused attention on the body as an “icon” emerging from nothingness. The blurred and distorted figure, and its elongated limbs, contributed to the idea of a disappearing image. The remaining abstract form is like a trace, suggesting the passage of time and our physical impermanence.

How do these ideas tie into a body of work like Anatomy of Desire (2008), in which you engage with the performance of sexuality — with exhibitionism?

Anatomy of Desire, as you rightly point out, engages with the performance of sexuality, but also with identity and desire. I was also interested in a notion intrinsic to photography and lens-based media in general: the gaze, and its related questions of seeing and being seen, of revealing and concealing. I started this project in 2008 after a traumatic personal event triggered a long period of insomnia. During that time I explored and took part in New York City’s gay nightlife, including illicit sex parties, as a way to face my own dark side and find catharsis. Sometimes accompanying my gay friends, sometimes wandering on my own, I photographed exclusively with my BlackBerry’s camera — the first generation of cell-phone cameras, several years before the advent of Instagram and the proliferation of iPhone photography generally.

The spectacular and almost theatrical aspect of the scenes I witnessed fascinated me, as did the tension between the observer and the observed/exposed, and the shifting nature of these roles. I was also intrigued by the way my camera’s extremely low resolution created texture and gave the bodies a sculptural quality while at the same time blurring the contour of the human figure and reinforcing its dissipation. The dematerialized surface of the image seems to mirror the fleeting aspect of the close and brief encounters I photographed. I see a parallel between the mechanism of desire and the mechanism of photography in the longing to retain a momentary experience that is already gone once it has been captured by the camera. It’s interesting that the same type of device I used has now become a tool to facilitate intimate and sexual encounters, notably through apps like Grindr. Some of the images in the series are presented as fragments and significantly enlarged to the limit of abstraction, whereas others are printed at a much smaller and intimate scale, with the image visible in its entirety to allow viewers the possibility of closer inspection.

The images in this series also address issues of privacy and surveillance, which are particularly relevant in a society where governments, media (including social media), and individuals themselves record and transmit every moment, movement, and conversation. In this context, our intimacy is often “acted out,” or performed, and the boundary between the private and the public becomes increasingly blurred as the private sphere offers itself as spectacle.