The Many Faces of Boko

Against a current of extremist violence, Northern Nigeria struggles to modernise Koranic schools

The day before Eid al-Mawlid, the birthday of the Prophet Mohammed, green and white bunting dangled across a dusty street busy with goats and children in the heart of Kano city. Down a narrow lane off a textiles market, the largest in Nigeria’s restive north, I reached an Islamic school called Makarantar Mal Tadda, its awning painted yellow and green in imitation of the country’s secular public institutions.

Roughly four hundred students attend Makarantar Mal Tadda, and thirty of them, known as Almajirai, call it home. Traditionally, the Almajirai are nomadic students sent to live with religious teachers, and their sole curriculum is the recitation and memorization of the Koran. But in a bid to help Nigerians survive in what is now Africa’s largest economy, Koranic schools are slowly embracing change.

Inside Makarantar Mal Tadda, I passed the Almaijrai’s quarters, a series of small rooms stacked with worn pillows and blankets. One student sat on a low stool repairing shoes, working by the fading light coming through a single window. On the wall behind him, someone had clumsily spelled out “Maddirisa Usama Bn Ladan” (“School of Osama bin Laden”). Teachers told me they hadn’t noticed the graffiti, and the students didn’t seem interested in it either.

In a tidy classroom upstairs, the morning’s lesson was still chalked on the blackboard. Wakil Ishehu Abubakar, the sixty-five-year-old academic dean, explained to me how the Almajirai, who were previously taught only the Koran, had started learning English and Arabic. “This school is more than a hundred years old,” he said. “ Now, it is modernizing.” On the board, an Arabic word was framed by two translations, one in English, the other a phonetic transliteration in ajami, local Hausa written in Arabic script. This secular education is known in Hausa as boko, a word anyone following recent news from Nigeria has come to learn.

Over the past five years, militants from Boko Haram have killed thousands of people in an attempt to establish a pure Islamic state. In March, the group’s abduction of nearly 300 schoolgirls who had dared to take a science exam in the northeastern village of Chibok sparked global outrage. Boko is widely translated in North American media as “Western education,” and Boko Haram as “Western education is forbidden,” but the word is multifaceted. In addition to secular or Western education, it can refer to the local elites who have received such schooling, or simply to Hausa written in Roman script.

Within Nigeria, traditional Islamic education, too, is frequently cast in narrow terms. The country’s estimated 9 million Almajirai are seen by the government as essentially illiterate, and President Goodluck Jonathan, an evangelical from the Christian-dominated South, has claimed that Koranic schools are recruiting grounds for Boko Haram. The United States, which funds counterterrorism initiatives in Nigeria, is equally suspicious of such links — one Nigerian academic told me he’d been sponsored to research Almajiri schools in almost every northern state. He found that the schools and terrorism were unconnected.

On the ground, the picture indeed widens. Koranic memorization is integral to the North’s educational traditions, but few people are opposed to seeing the practice combined with other forms of knowledge. A new generation of teachers believes that the discipline cultivated by memorization is a powerful aid to further learning and an important educational entry point for the country’s most marginalized children. And so, schools like Makarantar Mal Tadda are teaching “Western” subjects for the first time — striving, against the current of extremist violence from Boko Haram, to adapt to a modernizing society and the competitive economy of a country where nearly half the population is under fifteen years old and unemployment is soaring among young adults.

Such efforts have been aided rhetorically, at least, by the Nigerian government, which announced in March that it would begin taking a “soft approach” to counterterrorism. As part of this strategy, schools have been charged with becoming the nation’s “laboratories of peace.” But many in the North argue that the government is underfunding education, even as it continues to pump billions of dollars into the security sector, contributing to the disaffection of Muslim youth.

Abubakar attended one of Nigeria’s formal public schools as a child, the first of his family to do so. “My brothers would mock me,” he said, recalling how they teased him for wearing a uniform. He went on to teach at formal schools for decades, and now instructs Almajirai in English and Arabic. “Teaching them Arabic,” he said, “puts students in a better position to understand the verses of the Koran for themselves, and not to be lured by miscreants who can introduce them to a wrong ideology.”

Koranic schools traditionally run on philanthropic donations from past pupils and the community. But Abubakar points out that to properly integrate secular education into traditional schools will require money to hire teachers of core subjects like English and math — a burden the government has never shouldered.

Nigeria’s public school system was created in the South during the mid-1850s by Christian missionaries. The “Westernized” formal schools they introduced were soon being viewed by northern Muslims as an attempt at conversion. And when the British colonial regime made English the country’s official language, a whole generation in the North was made effectively illiterate overnight. The eventual result was a bifurcated education system comprising the public formal schools and the Islamic schools. The consequences have been stark: today, the literacy rate among children ages five to sixteen in much of the North is below 46 percent, and as low as 15 percent in some places, compared with over 70 percent in the South.

The push for modern education among Muslims in the North was a product of the Izala movement of the 1960s. Supporters advanced a modern vision of Islam and rallied simultaneously against the Nigerian state and the old Sufi order. They also advocated for suffrage and education for women, backed by the Koran. One of Izala’s most respected leaders was Sheikh Abubaker Gumi, a cleric based in Kaduna, the capital of Kaduna state, which lies on Kano’s southern border. Gumi published a Hausa translation of the Koran in 1980 and was branded a radical for broadcasting sermons on public radio. Opponents labeled him and his followers boko. Although Gumi saw all forms of education as sacred within Islam, an Izala splinter group that rejected modern education and government institutions went on to lay the foundations for Boko Haram.

Since 2004, basic primary education in Nigeria has been free and compulsory by law, but the underfunded public system, mired in corruption and struggling to accommodate the bulging youth population, continues to struggle. I visited a public school in the North where computer training was compulsory for students even though the building didn’t house a single computer. In some classrooms old benches were cluttered together in piles, and in one the roof had collapsed — though the school’s walls were freshly painted.

Sheikh Abubaker Gumi’s son, Dr. Ahmed Gumi, told me the biggest problem Islamist reformers face today is no longer resistance to education among Muslims, but funding. Public primary schools, though they cost nothing to attend, required families to spend money on books, uniforms, and other supplies. Though the figure might amount to less than $15 a month, it was more than many Northern families could afford. To attend Koranic schools, children needed only a wooden slate, but for those schools to offer some of the broader education promised by the public system and still cater to marginalized families, someone would have to bridge the gap in funding currently being filled by volunteers and donations. “People want education,” said Gumi. “Open a school and they will rush. Even in Maiduguri, where the Boko Haram issue is there, they still want to attend school.”

To get a sense of who still opposed secular teaching in Koranic schools, I visited Rigasa, a conservative Muslim quarter of Kaduna city. Dahiru Bauchi, a staunchly traditional Sufi cleric widely thought to be the main opponent to modernization, sat in a large room surrounded by dozens of kneeling adherents. His robust figure was swathed in embroidered robes; on his head was a white and silver turban. I was ushered to a cushioned pouf beside him, my translator and I the only women in the room. The men around Bauchi wore crisp shirts and prayer hats. They took photos of him using smartphones or tablets, and approached him to kiss the back of his hand and murmur requests for blessings.

Bauchi oversees a network of some 150 Almajiri schools. When I asked him what he thought about the introduction of Western teaching in Koranic institutions, he raised his voice to address the entire room and pressed his hands together in front of his chest. To my surprise, he announced that he believed secular and religious education could be combined. “The world is changing,” he said. “It’s like the right and left hand: the right hand is the Islamic education, the elegant hand, and the left hand does the everyday work.”

In modern Nigeria, he added, the Almajiri school system is changing for the better, but like Gumi he emphasized the need for government support. “We in the North are citizens too,” he said.

Bauchi, who comes from a family of farmers, never received a formal education, and he’d always seen secular learning as a distraction from religious scholarship. By way of explaining his seeming change of heart, he told me about his children — fathered, he claimed, from among no fewer than sixty wives. Thanks to secular education, he said, many of them had earned university degrees and become doctors.

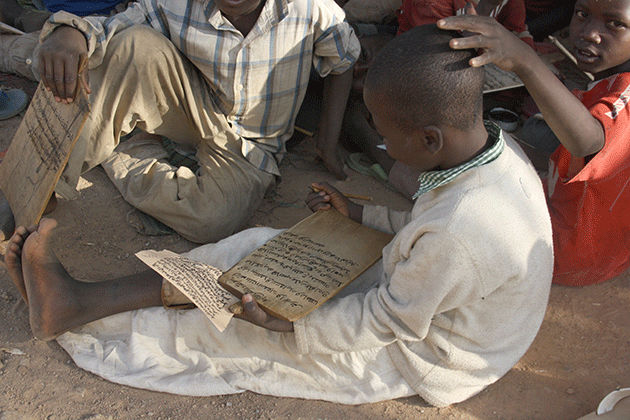

A young Almajiri transcribes Koranic verses onto a slate in the street outside Idris Suleiman’s school in Kabala Doki, Kaduna © Caelainn Hogan

Across town in the upmarket neighborhood of Kabala Doki, I met a thirty-three-year-old mallam (learned man) named Suleiman Idris, who is part of the younger generation of modernizing teachers. Idris’s own father ran a Koranic school in Kaduna, but at the age of ten Idris was sent as an Almajiri to Kano, in order to avoid any perception that he might be receiving special privileges as the son of a mallam. Idris didn’t receive any formal education until, at nineteen, he managed to gain admission to a diploma course at a community college. He went on to earn a degree in Arabic language.

With aid from the British government, Idris was spearheading the integration of secular education into the Koranic school he had inherited from his father. He was also receiving support from a statewide pilot program that provided training and remuneration for volunteer teachers to instruct students in English, math, Hausa, and sociology. But the support was coming only at the state level. “The [central] government comes and says they will help,” he said, “but the help never comes.”

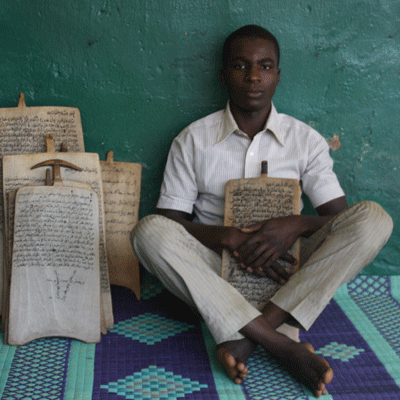

As the first prayer rang out in the chill morning air, I watched Idris’s students spread mats on the street outside. Approximately fifty pupils, ages six to eighteen, sat in a long line against a wall. Instead of textbooks, Idris distributed to them pages from an unbound, handwritten Koran. Clutching their pages in one hand, the students transcribed the Arabic verses onto smooth wooden slates that they rested across their knees. The ink they used was made from fruit, the pens whittled from sticks. Like Western schoolchildren drilling multiplication tables, they repeated verses in unison, washing their slates clean once they’d committed a verse to memory.

Idris told me that in the afternoons, after lessons were finished, he and his wife would cobble together whatever food they could for the boys, but that some inevitably ventured out to the streets, brightly colored plastic bowls in hand, to beg for food. Many people in the North consider the Almajirai to be street kids, but the tradition is deeply ingrained in the region’s culture. Before a family moves into a new house, they will ask an Almajiri to bless each room by reciting from the Koran. For a new bride, an Almajiri will write out special Koranic verses on a slate, after which the ink is washed from the wood with pure water and the bride drinks it, imbibing the sacred verses in communion.

To demonstrate the progress being made at the school, Idris introduced me to Sai’d Abdulrakman, a tall and soft-spoken seventeen-year-old Idris regarded as one of his most promising students. Sai’d had arrived the year before from the village of Gidan Nasaw, a four-hour drive to the north. His father had sent him to complete his Almajiri education before he’d finished primary school, and at first he couldn’t read or write.

Idris began by teaching him the sounds of the Arabic alphabet, letter by letter, before moving on to the Koran. Sai’d first memorized the verses by reciting and transcribing, then learned the meanings of the words. That year, he’d committed five of the Koran’s 114 chapters to memory. Asked to translate the word “light” into Arabic, he offered two synonyms. “It can take me four or five years to memorize the Koran in full,” he said in hesitant but precise English, which he was learning in his spare time.

A week after my visit, with permission from Idris, Sai’d and I made the long trip back to Sai’d’s village in Kano. Gidan Nasaw lay more than three miles off the tarmac road from Kaduna, and for twenty minutes as we neared the village our car struggled along a barely decipherable sand track. The radio buzzed with news of a suicide bombing that had killed seventeen people some 400 miles away in Maiduguri, to the northeast in Borno State, the day before.

After passing fields of maize, potatoes, and yams, as well as a caravan of six camel traders who had traveled all the way from Niger through unmarked territory, we reached the handful of mud-brick houses where Sai’d had grown up. We were welcomed by his father, Haruna, a wiry man in an impeccable white tunic, while children crowded around us and Sai’d’s mother and another woman who had raised him tended to pots.

Sitting on a mat spread out on the ground, Haruna spoke of his own Almajiri education in Maiduguri. When he returned to the village as an adult, he told us, he managed to receive some basic education and found that Koranic study had instilled discipline. “The combining of the Boko education and Koranic learning is fantastic,” he said. “We embrace it fully.”

Two of Sai’d’s younger siblings, a girl and a boy, attended the public primary school, which lay far outside the village. The boy would eventually be sent away to complete his Almajiri education, too. Sai’d’s older sister, who was barely nineteen, cradled a newborn; she had never attended school. Two lanky teenagers, childhood friends of Sai’d’s who were also Almajirai, loitered nearby. In a village with no electricity, each boy was fixated on his cell phone, earphones dangling from one ear. “When [Sai’d] returns to the village with the knowledge he has gained,” said Haruna, “his education will benefit the village. If he is a doctor, if he is a vet, we will benefit.”

On the drive back to Kaduna, Sai’d told me his dream was to attend secondary school, and then university. He wanted to learn agricultural science so that he could return to the village and contribute his skills, perhaps becoming a teacher himself. “If I can find a sponsor,” he said finally, as though pinching himself awake.