Art Beyond Politics

At the New Museum’s latest show, Arab artists take up — and look past — regional politics to question their own modes of expression

So many of today’s iconic images are made in the Middle East. Gaza’s scenes of wreckage and dead children fill our screens this month; a little while ago it was news clips of masked men marching through Mosul, who soon tweeted pictures of their beheaded or crucified enemies. The pornographers of jihad have an eye for memorable obscenities. Who can forget, once seen, the snuff videos of Muammar Qaddafi or Saddam Hussein?

The region doesn’t only produce images of awfulness, of course. In the springtime of the Arab Spring, the festival of Tahrir was inspiring to behold. So were videos of unarmed crowds surging through clouds of tear gas to defend their public squares. Less inspiring, though just as riveting, are the real-estate spectacles of the Gulf — Babelian skyscrapers and filigreed soccer stadiums that seem to have arrived from the future as imagined by Zaha Hadid.

For visual artists working from the region, this surfeit of spectacles poses a challenge. When everyday life — at least as it is experienced via a computer screen — regularly throws up these images of terror and drama and the technological sublime, how can a photographer compete?

The exhibits at the New Museum’s current show, Here and Elsewhere, put forth a fascinating range of answers to this question. The show, which occupies all five floors of the museum in Lower Manhattan, gathers the work of forty-five artists from the Middle East. There are too many sensibilities on display to take in during one visit, but the show isn’t at all a hodgepodge. Each exhibit is more or less explicitly concerned with the nature of images: who makes them, who looks at them, and how their meanings change with time. In contrast with the immediacy of news reports and made-for-consumption spectacles, the best pieces at the New Museum show offer their own images with skepticism, and even, at times, with distaste. This is art that doubles as art criticism.

Such thoughtfulness — call it conceptualism — is remarkable, given that many of the exhibits deal with events still dripping blood. This isn’t a show of protest art, though it sometimes takes protests as its material. Fictionville, a series by the Iranian artist Rokni Haerizadeh, uses stills from YouTube videos of political demonstrations — in this case, bare-breasted women protesting Islamism — in which protesters and police are painted over roughly, becoming half-human, half-animal hybrids (one inspiration for the series, we learn from the excellent catalog, is a book of Persian folktales). Haerizadeh’s painting makes clear which side he isn’t on — the forces of order have pigs’ heads or devilish horns — but by turning news footage into something stylized and mythical, he takes our attention away from the political subject and draws it toward the artist’s techniques.

Subversive Salami in a Ragged Briefcase (2014), by Rokni Haerizadeh. Courtesy the artist and Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde, Dubai

The show takes its title from Jean-Luc Godard’s Here and Elsewhere, one of the great essay films of the nouvelle vague. In 1970, Godard was commissioned by Fatah to make an epic of the Palestinian struggle — every national liberation movement wanted its own Battle of Algiers — but he ended up making a movie about the circulation of images instead. The Palestinians Godard filmed in the camps of Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria were in some sense always posing for the camera. Sheer visibility was a victory for them, and the fedayeen loomed larger in the world of images than they ever did on the battlefield. Jean Genet, who stayed in the camps at the same time Godard did, once quoted Arafat as saying, “[Foreigners] take photographs of us, they film us, they write about us, and thanks to them we exist. And then suddenly they may stop, and for the West and all the rest of the world the Palestinian problem will be solved simply because no one sees its picture any more.”

Heroism is the first casualty of Godard’s film, and the artists at the New Museum take a similarly suspicious view. The exhibits I spent the most time with find politics in unlikely places — not in the public posturing of leaders, nor even in movements of popular resistance, but in the unrehearsed moments of everyday life.

Lamia Joreige’s ongoing series, Objects of War, is an ideal entry point to the show. Her exhibit features six old-fashioned televisions showing interviews of men and women who lived through the Lebanese Civil War. Each subject talks about a personal memento of the conflict. Their stories are thus fixed around concrete particulars — a flashlight, a pack of playing cars, a jerrican — that are shown in display cases around the room. (Several of the subjects are also artists in the show, which is weighted in favor of Lebanese work.)

It takes time to listen to the interviews, and that is the point: these are stories that don’t make the news and don’t come in sound bites, yet they give a vivid sense of daily life in the midst of deadly abstractions. Listening to the tales, one is also reminded how much the current wave of conflicts, increasingly brutal and sectarian, resembles a large-scale version of the long Lebanese war — a battleground that also drew in its neighbors and made a mockery of settled alliances and ideologies.

To find politics in the midst of the everyday is something documentaries do at their best, and Here and Elsewhere features some extraordinary examples of the form. Abounaddara, a collective of anonymous video artists, has been shooting and posting films of day-to-day life in Syria since the beginning of the uprising in 2011. One of the videos shown here is an interview with an Alawite woman talking about how she became aware, as a schoolgirl, of the fact of sectarianism. I was immediately reminded of how Americans tell stories about becoming conscious of race. In both cases, you are listening to stories of political baptism — of being born into a history one has no control over, and which therefore seems slightly artificial, but whose consequences are real and pervasive.

Another documentary, Khaled Jarrar’s Infiltrators, follows Palestinians seeking entry to Israel through checkpoints and over walls. There are moments of confrontation, but most of the footage shows the subjects walking through fields, talking on cellphones, trying to start the car, etc. The film shows what politics with no heroes looks like — or else it shows a heroism of small gestures, performed to preserve one’s dignity rather than to vanquish the enemy.

For me, the revelation of the show was the studio portraits of Hashem al Madani. Madani ran a small commercial shop, called Studio Scheherazade, in Saida, in southern Lebanon, for more than fifty years beginning in 1953. He sometimes took a hundred portraits of ordinary people in a day — for IDs, weddings, graduations, and everything else. Madani made no attempt to unmask his sitters or to subject them to ironic scrutiny. They were allowed to pose just as they wanted, which gives his work a compelling mixture of earnestness and make-believe.

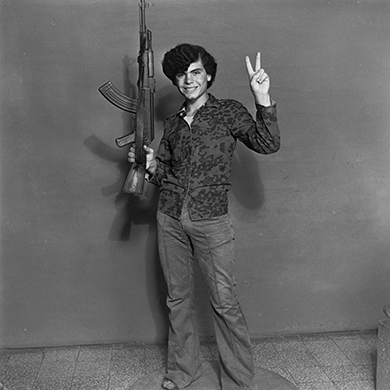

“Hashem El Madani. Palestinian resistant, Studio Shehrazade, Saida, Lebanon, 1970– 72,” by Akram Zaatari. From “Objects of study/The archive of Shehrazade / Hashem el Madani / Studio practices,” 2006. Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut/Hamburg

His work at the show includes a series from the seventies, when young men in bell bottoms posed for him with rifles à la Palestinien, as well as portraits of parochial schoolgirls and serious-faced Syrians (the Ba’ath Party occupied the floor above the photo studio). There are also several images of two people mimicking Hollywood kissing scenes. This would have been unseemly for boy-girl couples, and so all the shots are of men kissing men or women kissing women, in various states of awkwardness and repressed hilarity. In Madani’s portraits, we get a glimpse of private fantasies, political or otherwise, made public.

Madani closed shop in Saida about ten years ago, but his archive of photos — there are more than a million — is now part of the Arab Image Foundation, a Beirut nonprofit established in 1997 with the goal of preserving photography from the Arab world. One of the founders, Akram Zaatari, curated the New Museum’s Madani series; Zaatari also has an exhibit at the show, which includes a contemporary video of him and Madani, as well as a triptych of large interiors of Studio Scherazade in its heyday. In these shots, portraits hang from the walls like icons in an Eastern church, while fluorescent lights fill the workspace with an antiquated sci-fi glow. A desk squats in the foreground, cluttered with the tools of the trade circa 1970, which have the mysterious significance of objects in an etching by Dürer. It is typical of the show that we should be confronted not only with the art, but the conditions of its making. This doesn’t dispel the magic of the images, but it does ground them in a particular time and place.

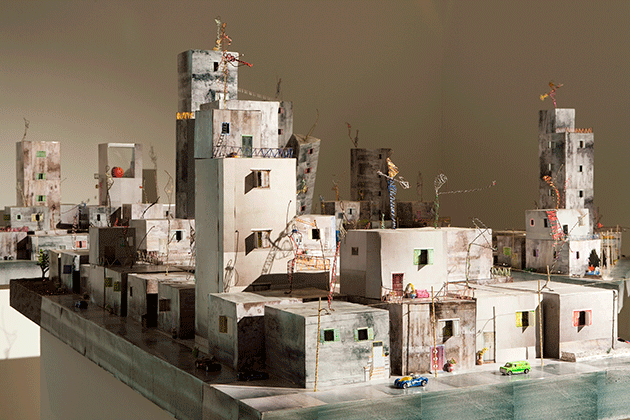

The eeriest exhibit, which has stayed with me in the days following my visit, is Wafa Hourani’s Qalandia 2087. The installation is a diorama built of simple materials, imagining what the Qalandia refugee camp, situated just west of Jerusalem, will look like one hundred years after the first Intifada. The camp is an orderly sort of ghetto: one of its taller buildings is conspicuously aslant, but the roads are straight and lined with prim little streetlamps. The security wall that cuts through the real Qalandia has become a wall of mirrors; on the other side of it — the Israeli side — are a nightclub with a goldfish tank and an airport with toy jetliners.

“Qalandia 2087, 2009,” a mixed-media installation in six parts by Wafa Hourani, photographed by Wilfried Petzi.

Walking through the space of the mock-up, which is about half the size of a handball court, you are made to think what it would be like to live in or visit such a place. And as you approach the mirror-clad separation barrier, you’re confronted with the image of yourself in two very different landscapes — as though asked to choose which side you’re on, or to think about the restrictions such a choice might entail. Like several other exhibits in the show, Qalandia 2087 suggests the power of images to limit the imagination, by reflecting back at us the picture of ourselves we would like to see, or might prefer to see in place of another, perhaps truer one.