Discussing On Immunity: An Inoculation with Eula Biss

Eula Biss discusses vaccinations, motherhood, and metaphors

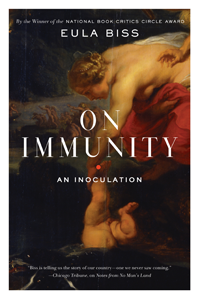

In her latest book, On Immunity: An Inoculation, Eula Biss examines the myth of Achilles, the otherness of vampires, and early vaccination methods involving pus from cow blisters—investigations all undertaken to show how and why we are obliged to protect each other as human beings. (A portion of the book appeared in our January 2013 issue as “Sentimental Medicine.”) Herself a new mother, Biss struggles with newfound fears of the world around her, while determining how best to protect her infant son from dangers, internal as well as external. What she finds, often, is a surprisingly porous boundary between science, politics, and the very big business of public health. With the same sort of intellectual shrewdness and precision that characterized her National Book Critics Circle Award-winning Notes from No Man’s Land (2009), Biss persuades us that our fates are more mutually dependent than we had ever imagined. I asked her six questions about the book via email.

In her latest book, On Immunity: An Inoculation, Eula Biss examines the myth of Achilles, the otherness of vampires, and early vaccination methods involving pus from cow blisters—investigations all undertaken to show how and why we are obliged to protect each other as human beings. (A portion of the book appeared in our January 2013 issue as “Sentimental Medicine.”) Herself a new mother, Biss struggles with newfound fears of the world around her, while determining how best to protect her infant son from dangers, internal as well as external. What she finds, often, is a surprisingly porous boundary between science, politics, and the very big business of public health. With the same sort of intellectual shrewdness and precision that characterized her National Book Critics Circle Award-winning Notes from No Man’s Land (2009), Biss persuades us that our fates are more mutually dependent than we had ever imagined. I asked her six questions about the book via email.

1. What contribution did you want this book to make to the debate in America over vaccination?

Working on this book was an opportunity for me to explore why I was vulnerable to certain fears around vaccination, and why I found some of the misinformation about vaccination seductive. I do hope that it will offer insight into why we are so ready to be suspicious of this technology. I also hope that On Immunity might shift the tone of the debate, which can be quite vitriolic. At times the conversation seems to be dominated by mean-spirited trolls. This is alienating to those of us who dislike trolls, but also damaging in other ways. When I first began spending my evenings reading articles about vaccination in popular publications, I was disturbed by the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) notes of misogyny I was hearing there. The message sometimes seemed to be something along the lines of, “If mothers weren’t so stupid and bad at science, they’d understand that they should just vaccinate their children.” My book is addressed directly to mothers, with the assumption that they are intelligent and thoughtful, in part to contradict that offensive message.

2. Much of the book revolves around your decision to immunize your son, which you relate to larger fears inherent to parenting. How did your relationship to public-health issues change with the birth of your child?

When my son was born, I still thought that many of the decisions I was making were solely relevant to his health. But the degree to which my newborn’s health depended on my health, and mine on his, challenged me to begin thinking a little differently. That was one of the great lessons of infancy. By the time my son was a few months old, I was thinking not only about how his health might affect mine, but also how it might affect our community. I was reading about hepatitis B at the time, and was fascinated by the important role that the vaccination of newborn infants plays in keeping rates of hep B low across the population at large. Targeting only “high risk” groups, which was the original public health policy for hep B, did not accomplish what the mass vaccination of newborns has accomplished. Was it my newborn son’s duty, as a person born into this society, to participate in maintaining the health of the people around him—I began to think it was.

3. In On Immunity you attribute at least some degree of anti-vaccination sentiment to capitalism’s self-serving influence. Where else do you see this influence at work?

3. In On Immunity you attribute at least some degree of anti-vaccination sentiment to capitalism’s self-serving influence. Where else do you see this influence at work?

Yes, we may be consumers, of health care as well as many other things, but that doesn’t mean that it always serves us best to think like consumers. Health care is one of those areas, like art-making or community-building or education, where the consumerist approach of trying to get as much as you can for as little as possible can be counterproductive. As a teacher, I’ve had ample opportunity to observe what consumerism does to education. Students who approach their education as consumers may be passive, may want a product not a process, and may expect learning to feel like entertainment. Learning tends to hurt more than entertainment, and the inevitable disappointment felt by the consumerist learner is often interpreted as a defect in the product. The loss there is twofold—the learner loses the opportunity to learn, but also loses the awareness that she is responsible for that loss. This is not to say that we shouldn’t be looking hard at the high cost of education, and the low returns some students get for that cost. We should absolutely interrogate the economy of education and its corruptions, just as we should interrogate the economy of health care and its corruptions. But we aren’t served any better, within these troubled systems, by failing to understand our personal role and responsibilities.

4. The essays in your last book, Notes from No Man’s Land, often employ unconventional forms—one, for instance, juxtaposes aphoristic statements. In many ways, On Immunity explores its arguments more traditionally. Do you see this difference as an evolution in your writing style, or is it something you felt the subject demanded?

The style of my writing is often a reflection of my style of thought, which changes from work to work. Part of the project of On Immunity was to critique a habit of thought—let’s call it loose association—that happens to be a habit of mine. When I saw a lot of loose association happening in the public discourse around vaccination, I recognized it immediately. That style of thinking has been artistically productive for me, but in this book I was forced to examine the dangers of it. I had to stand back and look at myself think and then think about what was wrong with how I was thinking. That process was uncomfortable and unsettling and, yes, resulted in writing that is stylistically quite different from much of my other work. I could not relax into my usual habits as a writer while I was examining my habits as a thinker. I think this book represents some important growth for me. But of course I’m looking forward to indulging my bad habits in whatever I write next!

5. You make frequent references to Susan Sontag throughout the book, particularly to AIDS and its Metaphors (1989). How has she influenced your work?

I’m indebted to Sontag for, more than anything else, permission to think. Thinking on the page, unprotected by characters or scene or story, can be terrifying. And I always worry that I’ll be boring if I allow myself to just think. One of the things I love about Sontag’s essays is that the thought is the drama. She thinks unapologetically, and with such vivid force! I find her thinking thrilling regardless of whether or not I agree with her. In writing On Immunity, I kept gravitating toward ideas and that gravity both excited and frightened me. I turned to Sontag as a guide in part because she seems so at ease, so at home in ideas. But some of her subject matter is also related to mine. I read Illness as Metaphor for the first time when I was in college and Sontag was the first writer I had ever seen think about metaphor, rather than through it or with it. The power of that exercise never left me, and so I am indebted to Sontag for that, too.

6. Much of On Immunity confronts a common American perception that the gravest threats to ourselves and our families exist outside our homes. You note, for example, that mosquitoes pose an astronomical threat to human life while sharks claim only a handful of victims each year—yet we’re likely to fear sharks more, because they’re unfamiliar to us. How do you think the notion of public versus private danger needs to be reassessed?

We could begin by understanding ourselves as dangerous. Dangerous to others, yes, and also dangerous to ourselves and our children. This is supported, in some ways, by statistics—women are most often murdered by a man they are living with, and children are most often kidnapped by a parent, and so on. When we understand ourselves as dangerous, the home ceases to be the highly fetishized space it has become and is revealed as just another container for mundane danger. I came to thinking about myself as dangerous through writing about whiteness in Notes from No Man’s Land. When I encountered the subject of public health with a readiness to think of myself as dangerous, primed by conversations about race and social power, I was surprised by how many well-accepted attitudes I was forced to refuse.