Introducing the February Issue

Christopher Ketcham investigates Cliven Bundy’s years-long battle with the BLM, Michael Ames examines the economics of incarceration, Annie Murphy reflects on Bolivia’s lost coast, and more

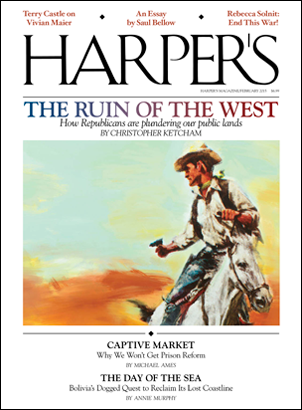

“Good fences make good neighbors.” It’s an oft-quoted line from Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall,” and one that’s often misinterpreted — Frost means to question the concept, not endorse it. But by the end of Christopher Ketcham’s February cover story, “The Great Republican Land Heist,” I found myself wondering if some sturdy fences might be useful after all. Ketcham investigates Cliven Bundy’s years-long battle with the Bureau of Land Management over the estimated $1.1 million in unpaid fees and fines he’s accrued for grazing his cattle on public property in Nevada. After spending time with Bundy — and his cadre of armed followers — Ketcham begins to wonder about the future of federally managed land. The goal of people like Bundy, Ketcham concludes, is “to attack the value of public lands, to reduce their worth in the public eye, to diminish and defund the institutions that protect the land, and to neuter enforcement.” As Ketcham explains, “What ranchers have always wanted, and what extractive industries in general want, is private exploitation with costs paid by the public.” It seems possible that they will succeed in achieving this goal — especially given the results of last year’s midterm elections. The consequences for the environment could be dire: “Grazing,” Ketcham writes, “is the chief cause of desertification in North America, and it has irrevocably altered the surviving ecosystems not yet reduced to dust.”

“Good fences make good neighbors.” It’s an oft-quoted line from Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall,” and one that’s often misinterpreted — Frost means to question the concept, not endorse it. But by the end of Christopher Ketcham’s February cover story, “The Great Republican Land Heist,” I found myself wondering if some sturdy fences might be useful after all. Ketcham investigates Cliven Bundy’s years-long battle with the Bureau of Land Management over the estimated $1.1 million in unpaid fees and fines he’s accrued for grazing his cattle on public property in Nevada. After spending time with Bundy — and his cadre of armed followers — Ketcham begins to wonder about the future of federally managed land. The goal of people like Bundy, Ketcham concludes, is “to attack the value of public lands, to reduce their worth in the public eye, to diminish and defund the institutions that protect the land, and to neuter enforcement.” As Ketcham explains, “What ranchers have always wanted, and what extractive industries in general want, is private exploitation with costs paid by the public.” It seems possible that they will succeed in achieving this goal — especially given the results of last year’s midterm elections. The consequences for the environment could be dire: “Grazing,” Ketcham writes, “is the chief cause of desertification in North America, and it has irrevocably altered the surviving ecosystems not yet reduced to dust.”

Climate change is on Rebecca Solnit’s mind in this month’s Easy Chair column, in which she contemplates the destruction visited on the planet by World War II. “From one perspective,” she acknowledges, in 1945 “what we call the world had never been more devastated. From another, however, the world was in magnificent, Edenic shape. No great garbage patch swirled around the Pacific, and albatrosses, sea turtles, and dolphins in remote reaches were not strangling on plastic they mistook for edible matter.” Her list goes on. Sooner or later, she reminds us, we will have to leave the Age of Petroleum behind. If we wait until nature forces our hand, we will have to make the transition “on a planet whose wreckage will be far deeper and wider than anything World War II produced.”

Michael Ames’s report on the privatization of prisons reaches a grim conclusion about the possibility of reform. The barbed-wire fences that surround the incarcerated may not make for good neighbors, but they do make for good business. Ames writes that private prisons are the “standard-bearers of innovation” in the corrections industry. “Their business model,” he explains, “is a simple exchange of money for services: the company owns or operates a secure building, and state or federal agencies pay out a per diem for each man, woman, and adolescent it incarcerates. The more prisoners held, and the longer they stay, the more money the company earns.” And the more money the company earns, the more it can contribute to the political campaigns of legislators who might, under other circumstances, be ideologically opposed to the troubling size, condition, and demographic makeup of the American prison population.

In her Letter from La Paz, Annie Murphy finds a country still mourning its Pacific coast, which was lost over a century ago in Bolivia’s war with Chile. Perhaps it’s no wonder: Bolivia is the poorest country in South America; Chile, whose per capita GDP is more than five times larger, is the richest. But, Murphy writes, “if Bolivia’s ambition to regain its coastline has been a source of pain, it has also allowed the country to imagine … the possibility of something beautiful and mysterious that is always just beyond reach.” Murphy talks to three soldiers who, in 2013, were arrested when they crossed the border into Chile while trailing smugglers. During their imprisonment, they glimpsed the water that used to be Bolivia’s. “All three,” she reports, “said they would only consider returning to the sea if it were Bolivia’s sea. As long as the ocean belonged to Chile, they would never go near it again.”

Our February Readings includes an excerpt from Wendell Berry’s new book, an argument against atomization, which reduces the body to “an assembly of parts provisionally joined, a ‘basket case’ sure enough”; selections from accounts of threats made against employees of the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management since 2010 (“He refers,” one account reads, “to a female U.S.F.S. employee hundreds of times as ‘Little Smoky Bear Girl.’ He repeatedly accuses the district supervisor of placing ‘Little Smokey Bear Girl’ to entice him with her ‘sex’ for the purposes of murdering him”); and a list of reasons given for missing work, collected by CareerBuilder (“needed to stay home to tend to depressed cat”).

Also in this issue: Terry Castle’s sensitive, sharp, and sympathetic examination of the work of photographer Vivian Maier, in whose self-portraits Castle sees a self-confidence that is “aggressive — almost regal”; an investigation into the modern art of the book review by our own Christopher Beha; new fiction by Alejandro Zambra, which was translated by Megan McDowell; a sketch of the ties that bound Lynn Freed, first as a child, then as an adult, to a servant in her parents’ home in Apartheid-era South Africa; and a photo essay by Samuel James, featuring a wolf-hybrid sanctuary where many of the caretakers are U.S. combat veterans.