Vegas Odds

An evening of gambling with the “Johnny Lunch Buckets” at the Westgate Las Vegas Resort & Casino.

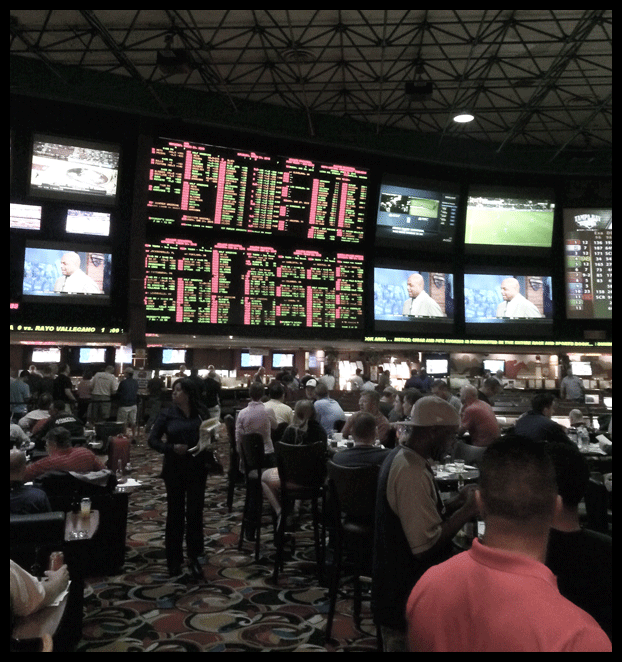

With more than thirty thousand square feet of floor space and sixty television monitors, the Westgate Las Vegas SuperBook room looked something like the mission control of sports betting. Even though the NCAA basketball tournament was underway, half of the screens were dedicated to horseracing. Watching them, I got the impression that there are at least a dozen races being run at every moment of the day, every day of the week, all over the world, giving players the possibility of gambling on Shakin Sugar, Jury Wise, or any one of a hundred other long shots.

1By the time Duke won the championship, an estimated $240 million in legal bets had been placed in Nevada.

I visited the SuperBook during the first weekend of March Madness. In the far-right corner of the room was a small community of seniors gathered to play the ponies. A man in a yellow cardigan began making the rounds, pausing at the bettor’s bureaus where members sat, their tip sheets fanned before them. The man spoke with the genial certainty of a self-appointed mayor, favoring his cane and dispensing some inside line. “Come on E,” he called to no one in particular. “Come back on the rail!” I couldn’t figure out which screen he was watching, but it didn’t matter; it was clear from his face that E had lost. The other side of the SuperBook was filled with tourists eating two-dollar hotdogs and sipping light beer, seemingly unaware of the emissaries of Old Vegas. They were focused on a big board overhead, waiting for the latest pronouncements from the oddsmakers on a day full of basketball games.1

The SuperBook room is tucked in the back of the Westgate Las Vegas Resort & Casino, a boomerang-shaped building known for most of its forty-six-year history as the Las Vegas Hilton. Since Westgate acquired the hotel in 2014, it has been working to renovate the building’s 2,956 rooms, about 200 of which will become time-share properties. Located just south of downtown, the Westgate was built to serve the original gambling district that’s now best known for the hallucinatory Fremont Street Experience—a deafening corridor that includes a 1,500-foot digital-screen canopy and the irrepressible neon cowboy, Vegas Vic. Downtown Vegas was once the cultural epicenter of the city, but it has been relegated to the periphery by the rise of the Strip, the main artery along which the mega-casinos of the last twenty-five years—the Bellagio, the Venetian—have all been built. Downtown is a budget alternative, making it well suited to the customers of Westgate Resorts, the “Johnny Lunch Buckets,” as the company’s senior executive, Richard Siegel, has described them.

During my stay at Westgate, sales associates were hard at work, snaring any sports bettors who made the mistake of making eye contact. I followed one, a dark-suited salesman who had a peremptory air and a faint dusting of acne. He escorted a young couple along a gallery of marketing materials, which included a large photo of a smiling David Siegel, the company’s seventy-nine-year-old founder. The visitors were dressed in what seemed the default attire for the day: the woman in shorts and a slightly oversized T-shirt, the man in jeans and a sports jersey. They shuffled along behind the salesman, who was explaining to them the benefits of purchasing time-share in the hotel. The couple nodded timidly.

Snaking out of the SuperBook were sports-betting lines composed of hundreds of gamblers, each one trying to size up where, when, and how exactly to lose their money. College basketball games don’t lack for gambling propositions—the moneyline, a straightforward wager on which team will win; the over-under gamble on the total number of points scored by both teams—but the most popular wager is the spread. The spread represents the predicted difference between the two teams in the final score of the game. If professional handicappers determine that one team should beat another by six points, betting on the second team is not wagering that they will win, merely that, if they lose, it will be by fewer than six points (in bettor’s parlance, that they will cover the spread). The science of oddsmaking, as such, is not to outsmart the average sports bettor, but to create a series of 50/50 propositions that keep him betting. The reason for this is that, win or lose, the sportsbook gets a cut of every wager. As long as betting reflects, in aggregate, that the likelihood of either team covering the spread is basically a coin toss, the house always wins.

In the Westgate Theater, several hundred mostly middle-aged men gathered to watch the eighth-seeded Cincinnati Bearcats play their regional rivals, the Kentucky Wildcats, the top-ranked team of the tournament. Throughout most of the first half, Cincinnati led, slipping behind Kentucky in the closing minutes. For a game that had the possibility of being a historic upset, the gamblers in the room seemed almost as bored as the handful of wives who sat nearby checking their cellphones. It was only in the second half, when Kentucky pulled away, that the audience grew animated. There was a 16.5-point spread on the game, which effectively meant that the duller the game became for everyone else, the more exciting it was for the gamblers. With thirty-three seconds left, Kentucky was up by seventeen, and pandemonium filled the theater. Bearcat bettors—who had rested easy when the game was close—were on their feet, screaming for a bucket. They got their wish and then one better, as Kentucky took an inbounds pass and, to agonized cries of their backers, decided to run out the clock.

After the game, two Cincinnati fans greeted each other on the casino floor. The older man was wearing a Bearcats polo, the younger a Bearcats jersey. Their team had just been smoked, the dreams of a championship dashed, but they nonetheless grinned when they caught each other’s eye. “At least they covered,” the younger one said. The two men high-fived.